- Joined

- Oct 6, 2021

- Messages

- 35

Folks, this report is for what was supposed to be a 5-day solo backpacking trip to Cheesebox Canyon in October 2025, but a half hour into the hike I enjoyed a serious fall descending through the ledges of White Canyon. This led to a full-scale SAR response and a helicopter ride to St Mary’s Hospital in Grand Junction, Colorado. (Spoiler: I do expect a full recovery, due to the help of many, many people I am incredibly grateful to.) Thus, the report is a bit different than what one typically finds on this forum, but I think it will be interesting, and maybe it will help someone avoid a similar situation in the future. Error analysis is pretty limited; it’s mostly a narrative of what happened based on my best recollection and the other evidence I have.

If you liked this report, you might also like my others, though note they are significantly less dramatic:

No AI used in this report or any of my other reports.

This photo was taken by one of the SAR (search-and-rescue) responders. It’s a detail of a larger photo of (I think) me being loaded into the helicopter that also captured something I feel is important: These individuals are having fun. My guess on the reason, having known a few folks who did SAR volunteer work and talking with them about how it works, is that they’re wrapping up a successful SAR mission at a reasonable time of day when the victim (me) was not only found alive but also conscious and oriented throughout the rescue (modulo exciting medications we’ll get to) and on his way to appropriate follow-up care. Regardless, it matters to me that my really bad day helped others have a good day.

I arrived at the trailhead around 11:00 AM. The area had clearly received lots of recent precipitation, for example water in the ditches alongside Highway 95 as well as actual drifts of hail in a few places. The trailhead itself had numerous puddles throughout the slickrock. However, by now the weather was great — sunny, little wind, not too warm or too cold. Occasionally, a crow would caw foreshadowingly from the junipers. After fairly extensive fooling around, I started hiking about 11:40.

My unsuspecting “before” selfie at the trailhead.

The standard route into Cheesebox follows a well-established social trail that winds northeast through a couple of cliff bands, then ledge-walks upstream in White Canyon about a half mile before descending a talus pile through the final and largest cliff band to the White Canyon wash. From there one can either ledge-walk the other side of White into Cheesebox, or follow the wash to the confluence and then climb the easy “Log Route” into Cheesebox.

I instead wanted to find my way down to the northwest, to link up with a cairn and social trail system that former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom etc. Boris Johnson and I had found a year earlier but had not been able to push to the top (see map below). There were only two unknown cliff bands really, and the first one was pretty straightforward. The second was considerably higher, but as I approached the rim, I saw a possible break corresponding to something I’d seen on the aerial photos in CalTopo. After some examination, it seemed that I could straightforwardly get about halfway down to the top of a fault filled with rubble, so if that fault also went, the whole cliff would go. I backtracked until I had a good view of the fault, which looked OK. Additionally, it seemed that I could just friction down to it, saving some backtracking.

View into White Canyon from somewhere on the descent, prior to the accident. Note the wash flowing from the precipitation.

However. Once I'd gotten down a few feet, the slope seemed sketchier than I’d anticipated — notably less grippy than I was expecting, with some sand rubbing off. The best course of action seemed to be step down to the next micro-ledge to increase stability. Unfortunately, this was not successful, and suddenly I was sliding down the slope. I had time for three thoughts: (1) “oh shit”, (2) “how is this happening to me”, and (3) “is this the end?”. Within that third thought was a pointer to a musing I’d had many times, namely: all consciousness ends, and all subjective experience is wholly internal despite our best efforts, so what value does sentience have? In particular, what is the value of sentience that is about to vanish? (E.g., clearly we value making folks comfortable at end-of-life, but why? They’re just gonna die soon.)

I was upright for a few moments, then bounced off what I assume was rubble in the fault I was heading for, which turned me 90 degrees to the left along the fault. I somersaulted down/above the rubble filling the fault an unknown number of times, and then suddenly I was staring at the sky with a thump.

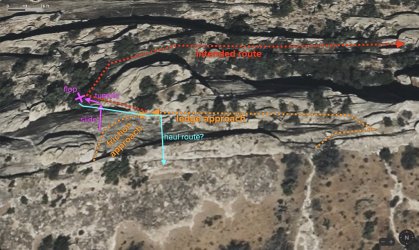

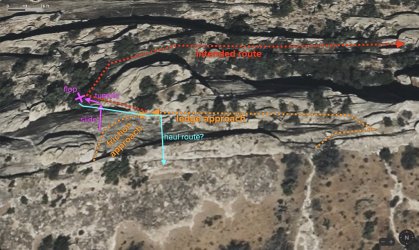

Overhead photo of the White/Cheesebox confluence area. The purple line is last year’s route out, entering from the upper right and ending at the trailhead. The solid red is my actual route this time, and the dotted red is where I’d planned to continue, to link up with the known route to the canyon bottom.

Detail of the accident location. The dotted red line is how I’d intended to proceed down the rubble-filled fault to the next major ledge, then east to the known route. “Ledge approach” is the first way I thought I could get down to the fault, and I suspect SAR used this route later. “Friction approach” is where I tried and failed to get down to the fault. In magenta is the two stages of my fall and where I ended up. The cyan “haul route” is my guess on how I was extracted to the wide ledge where the helicopter was.

I think it’s worth pausing here to bring in some future knowledge, namely the actual extent of my injuries (and final content warning, this is a pretty scary list). Later in the report I have some imaging so you can see exactly what I’m talking about.

It wasn’t random that it was my left hip that was all smashed up. It was because I lost my grip when I had my right leg squatted under me and my left stretched out to reach the next micro-ledge. Thus, I slid down the rock in a squatting position, upright, on the sole of my right shoe, so when I collided with the rubble, it was with my left leg straight out. In principle, I might have been able to recover into a roll or something like that, instead of just hitting the ground foot first, but without practicing the move and being so surprised, I think it’s unrealistic to think and move fast enough to put it together.

I believe that’s also why the second stage was somersaulting leftward (looking down the slope) down the fault rather than stopping after the first stage: my center of gravity was well to the left of that first impact, so it started me spinning, and I hit the ledge close enough to the next drop that I continued down. I suspect that all my injuries happened in the first collision, and landing on my backpack after the second stage absorbed enough energy that I didn’t get hurt further.

According to my GPS data (specifically, trace timestamps with intervals suggesting that I was moving rather than stopped), the fall occurred at 12:12 PM, i.e. not much more than ½ hour into the hike . I did have the presence of mind to not attempt getting up right away, but rather take a few minutes to gather my wits and decide what to do. I was in an awkward position — flat on my back, slightly head down — and mighty surprised, but nothing hurt and I could move all my fingers and toes. I couldn’t find any bleeding. I could reach my water bottle and drank some water. I wriggled out of my backpack straps.

I genuinely thought that after a few minutes I’d sit up, have a snack, and be on my way with some soreness and bruises. While I was in the shade, the weather was good, the situation seemed stable and safe, the remaining distance to hike was short, and I had about six hours before dark, so there was time.

Every few minutes, I’d try to pull myself into a sitting position, but I didn’t have the leverage and couldn’t do it, even after cutting away a small amount of brush with my fancy Japanese saw. Also, I was beginning to notice a pain in my left hip that was quite mild at rest but seemed to carry great depth if I did the wrong thing — I stopped several attempts to sit up or roll not because it became painful but because I feared the pain that lurked immediately beyond (and rightly so, as we’ll see later when discussing the rescue).

First-person view of my landing spot. I recall the area as being mostly level. I don’t know if that recollection is wrong or the photo is tilted.

So, sometime around 12:40 or 12:50, I admitted to myself that I really did have a major problem and needed help. Note though that I had no idea I was hurt as bad as I was; I thought at worst it was a hip dislocation.

I activated the SOS on my InReach. I did have a flash of worry when it didn’t send right away, but I was able to reach the brain of my pack, where the device was, and clip it onto the pack waistband instead, which had a more direct view of the sky. The SOS marked itself sent at 12:58. I also sent a satellite message to my spouse so she would hear I was in trouble from me rather than somebody else. Then I started waiting.

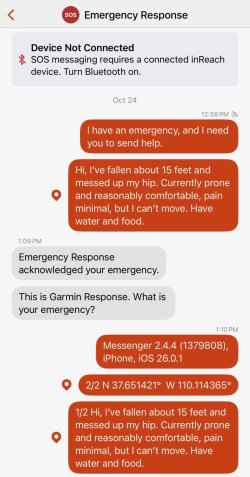

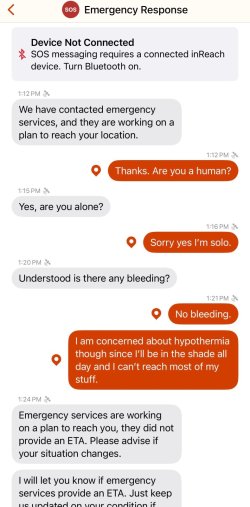

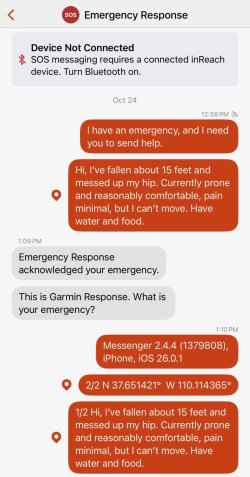

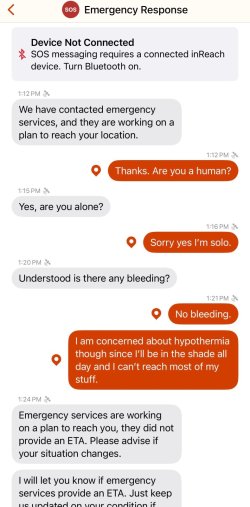

This is what my experience was. I had the device in LiveTrack mode already so it should have had a satellite fix.

Screenshots of the beginning of my conversation with Garmin. (Note: Disregard the Bluetooth warning; I made these images later when the device was turned off.)

Bottom line, IMO it would be extremely difficult to activate an SAR response accidentally.

I did observe that updating the Garmin people appeared to be a low priority for SAR once they had the information they needed, and especially once they found me, i.e., I’d guess your loved ones shouldn’t rely on Garmin for updates.

It appears that you can also schedule a test ahead of time if you’d like to actually try it.

Other important notes:

My most immediate concern was hypothermia. The temperature was in the low 50s and I was presently comfortable, but I was in the shade, and if the wind picked up or I had to overnight, I might have a serious problem on my hands. I communicated this to Garmin.

I also had very limited access to my stuff, because my backpack was above and behind me, with the top opening pointing away. In particular, my jacket and sleeping bag were at the very bottom of everything. I passed the time by exploring what I did have access to and trying to get things a little organized, maybe move my pack to get into it, maybe get into a more comfortable position. None of this was particularly successful. The main tool I found was a Japanese pruning saw, and with some effort (it was not cutting the wet log I was lying on very effectively) I was able to jam some rocks and sticks under my left hip, which starting to hurt and seemed to benefit from additional support. I also found my Cheetos and ate two, though they weren't very appetizing.

My view while waiting. I’m a little annoyed this missed focus so badly because the clouds really were pretty.

Another tool that turned out quite useful was the selfie camera on my phone; I could use this to look behind me. The key item found was my pocket knife, which had exited my pocket but turned out to be within reach with a little shoving and prodding. I decided the situation was serious enough to ruin my gear and started cutting a hole in the bottom of my pack to access the jacket and sleeping bag I wanted.

Around this time, I thought I possibly heard a faint voice, though I was skeptical and concerned about wishful thinking. However, not long after, I heard a voice more clearly and yelled back, and I could even see someone across the canyon, which I though was White Canyon but perhaps just the side canyon I was descending. I decided this was good enough to believe and reported voice contact with rescuers to Garmin at 2:40, an astonishing response time of something like 1½ hours since SAR activation.

As noted above, at this point Garmin was still telling me they had no ETA. I suspect that keeping Garmin up to date is a pretty low priority for typical SAR teams.

A few minutes later there was an obvious, clear call. It occurred to me that I’d been dragging a whistle around for decades and never actually used it, and by gum it was on a pack strap that I had access to. So I responded with three whistle blasts and received back a clear and close “I’m coming!”, which I acknowledged with a single blast. Soon after that, a figure appeared at the top of the rubble crack I’d somersaulted down and asked how I was doing. I replied something notably hilarious along the lines of “been better”. I think he also asked about hitting my head and bleeding, both of which I reported negative. Then he said they were still trying to find a way down and vanished.

Finally, a boy of 12 or 13 in a San Juan County Sheriff uniform appeared in my little grove of piñons and we started chatting. He refused to move me into a more comfortable position (correctly, given my injuries), but he did get my jacket out of my pack, which helped immensely. It was a huge relief to have another human being present.

I know the sheriff’s deputy told me his name several times over the course of the rescue, but I’ve still forgotten it. I remember vividly that the name was Polynesian (I asked), so I think of him as the Polynesian kid. Every so often during the rescue I would spot him and blurt out “Hey, it’s the Polynesian guy!” and he would laugh.

I’ll add that this part of the narrative is a bit muddled, since there was a lot going on and I kept receiving exciting drugs.

Sometime around the arrival of the Polynesian guy, a helicopter made a few passes around the area. I realized the situation may be more serious than I thought it was. I think the chopper landed and stayed put until I was ready to get on.

At some point, three more individuals arrived with me: Mark, a BLM ranger; Tom (???), an air paramedic from Classic Air Medical, who is roughly my age and gave the usual grizzled, bearded outdoorsy guy vibe; and Hannah, another air paramedic who was very clearly Gen Z and wore dramatic eye shadow. These were the four people I saw the most of. I understand the rescue was quite a bit bigger (someone told me 30 people), but the bulk of that work was happening on top of the cliff.

I worried to Mark that he wasn’t getting paid (because of the government shutdown), but apparently he was due to some exception.

Helicopter waiting. I believe the three figures at the edge of the cliff are looking down at me. According to EXIF, this photo was taken at 3:39pm.

Things started happening. Someone put in an IV. I was still cold and asked for my sleeping bag, which someone dug out of my pack via the hole I’d chopped in the bottom. That helped a lot. It was pretty clear to the paramedics that I would be a litter case. I was OK with that and said I didn’t want to be paralyzed. I was easily reassured that wouldn’t happen, though in retrospect that confidence was misplaced given my L3 burst fracture and attendant compromise of the spinal cord passage.

Hannah actually ultrasounded my pelvis. Someone brought a gadget that she plugged into her phone, and I got ultrasounded halfway up the side of White Canyon.

At some point, it became largely a waiting game as the hoist was set up and sufficient volunteers arrived. Eventually, the team agreed to sit me up, and in preparation for that I received my first dose of ketamine (and also fentanyl IIRC). Ketamine is ... not my thing. At first it was kind of cool, I just got super high and said silly high things. But once the drug really kicked in, it sucked. My vision clouded over and instead I saw a shifting field of red/yellow/orange video game type pixelated hallucinations. During this, I could hear folks talking to me and preparing to shift me into a more sitting position. When the shift came, it was still incredibly painful. I could hear myself screaming and also see the noise and pain in the video game patterns. Eventually I came down enough to start chatting with my team again and realize that I was facing a really nice canyon view instead of the sky.

Hannah offered music. I requested “Never Gonna Give You Up”. I don’t think she ever played it, though I did remind her a couple times.

I said “thank you for helping me” to people a lot.

Eventually, someone in climbing gear showed up with a litter and the actual extraction started. I got more ketamine, had another bad trip, received an excruciating, hallucinatory transfer into the litter. Apparently my inflatable sleeping pad was a useful part of this, as it was one of my few possessions that showed up in the hospital with me. Someone put a climbing helmet on me. Hannah reached out of the haze and put safety glasses on me, which for some reason felt deeply meaningful.

First stage of the hoist, up the rubble fault I’d been hoping to descent rather than somersault down. 5:24pm.

Based on rope angles in these photos, I think the ropes were re-rigged after this first stage, and I was carried across the intermediate ledges past my friction slope to a steeper part of the cliff that was more amenable to a rope extraction.

Second stage hoist. The guy on the rim at left was in charge, I think. He was talking to the litter attendant and then yelling commands behind him, and then something would happen on the rope (us moving up or whatnot). 5:36pm.

I chatted briefly with my litter attendant (Adam?) and asked where he was from, thanked him for helping me. I think I may have told him some dad jokes, which was notable to the hoist lead above because I was communicating coherently. He was busting his ass and breathing hard. The hoist wasn’t too painful overall, just when I bumped into things.

I am pretty sure the lift was done manually, i.e., a team of people yanking on the rope somehow. Sounds like hard work and I appreciate it.

Finally I was over the lip of the cliff and on top, which was a wide, spacious platform of sandstone. There was one more transfer, I believe into the helicopter’s litter. I got more ketamine for this, which I didn’t want because of the bad trips, but I was persuaded that it was better than the alternative. I was vaguely aware of being loaded into the helicopter. Coming down there was the worst; I was caught in a time loop or something and couldn’t figure out what was real. I think part of the issue was that my working memory was one or two seconds long and it was continuous, unpleasant deja vu as I rediscovered things I knew I was rediscovering. For a while, I was convinced that I was a new consciousness self-assembling from the void. I believe Hannah spent a lot of time preventing me from touching helicopter things I shouldn’t as I discovered them over and over. Sorry about that.

Helicopter departing, I think. 6:15pm.

We lifted off around sunset and flew about an hour to Grand Junction. I’m pretty sure the view was spectacular but I was too high to enjoy it.

Excerpt of the helicopter ride. I think I filmed this myself, though I don’t remember doing so. I didn’t get a flight helmet, so I couldn’t communicate with the crew.

Landing on the roof of the hospital, the usual ER stuff started. I received lots of scans and talked to my spouse about they were going to keep me overnight; apparently I sounded perturbed, like that was an overreaction. I got a preliminary inventory of my injuries. Then I was in the ICU, awaiting surgery in the morning.

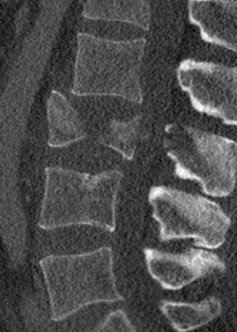

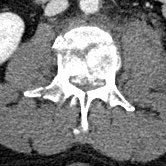

This is a fly-through of a 3-D model reconstructed from one of my CT scan series that touches on each of my main problems, this one being 201 slices at 2mm intervals. (I got a lot of imaging.)

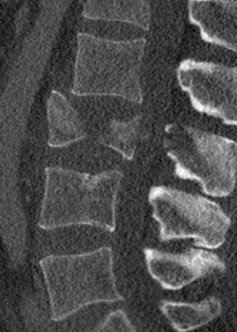

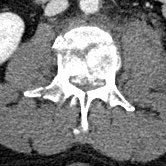

The fly-through doesn’t show the spinal injury very well, so here are some 2-D sections. The left panel is a section of my lumbar spine viewed from my left side; note the obviously smashed L3 vertebra. The middle panel is a top-view slide of L3, and the right panel is healthy L2 (the vertebra immediately above) for comparison.

Per my orthopedic surgeon’s chart notes: “Reid needs his pelvis fixed .... It is an unusual pattern .... his hip joint is not connected to the rest of his pelvis and is malrotated and needs reduction and stability.” (Reduction just means put the bones back where they go.) He described it to me before the procedure as (paraphrasing), “Your hip joint is fine but it’s not attached to the rest of your pelvis and that’s a problem.” I really liked him.

In addition to several broken bones that needed repair in order for me to be a functional human being, there were two quite concerning swords of Damocles: (1) spinal cord at risk due to the lack of space in L3 and (2) the bone shard threatening to pierce my iliac vein. Based on later conversations, I don’t think the second risk was well understood until the surgery. To be clear, I’m not salty about this; I think it was just not visible on the imaging.

I arrived at St Mary’s at 7:29 and was transferred to the ICU at 10:30.

My initial hospital wrist band at St Mary’s. That is ... not my name. Or my birth date. Do I really look 54!?

Surgery commenced at 8:30 am on October 25 (the day after the accident) and I left the OR at 3:45 pm, i.e., 7¼ hours in surgery. I had two procedures done by different teams back-to-back: first the spinal repairs, then the pelvis. I now have 37 pieces of metal hardware in my body (my chart has an inventory).

I spent a day or two in the ICU post-surgery, then transferred to a regular floor. My sister arrived on the 26th, and then my spouse flew in on the 28th. She was able to stay for a week or so. It was the first time for our two boys that both parents were out of town at the same time, but they were champs. I’m really proud of them.

On November 8, i.e. 15 days in hospital, we finally got the logistics for transport worked out, and I transferred by ambulance to in-patient rehab at St Vincent’s in Santa Fe, which is a lot closer to home. The ride was actually pretty fun; the scenery was great and I think I yammered with the EMT not driving for three hours or so. She had a lot of interesting things to say about ketamine. Also, and this was really surprising to the EMTs, the ambulance gurney was the most comfortable I’d been since the accident.

Me in hospital at St Mary’s in Grand Junction, in the only chair I was allowed to sit in, which was incredibly uncomfortable but also a success because I could get out of bed. I assume the photo is due to the massive effort required for the transfer.

Rehab was not much fun aside from the 3 hours daily of physical therapy (PT) or occupational therapy (OT), which was hard but really productive, and the therapists liked me because my prognosis was so good. At age 46, I was the youngest person in the unit by roughly 1,000 years. I flew through rehab and came home on November 13, i.e. 6 days in rehab. Then I had one of the local visiting nurses coming by twice a week. My spouse and I went back to Grand Junction for follow-up appointments earlier this week.

First piece of mail I received after coming home.

The current status as of today, December 5, 42 days or 6 weeks after the accident, is excellent. I have minimal pain, just two rounds of acetaminophen (Tylenol) overnight. I’m getting around well by wheelchair or walker. Excitingly, I start weight bearing on my left leg tomorrow, proceeding as tolerated, so hopefully I will be walking again soon. I hope to go back to work part-time next week (I have a desk job), with the key obstacle being not my health but my employer’s bureaucracy.

There is a possibly-apocryphal story that Alfred Nobel created the Nobel Prizes because he read his own obituary. That is, Nobel’s brother Ludvig died in 1888, and at least one newspaper (which may not exist?) confused the two and printed an obituary for Alfred headlined “le marchand de la mort est mort” — “the merchant of death is dead” — including the spicy quote “Dr. Alfred Nobel, who became rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before, died yesterday.” According to the story, by reading the premature obituary, Nobel learned what people really thought of him, decided he didn’t like it, and established the Prizes in order to change that reputation before he really died.

The relevance is that for me, a key part of this accident and recovery experience is learning what people really think of me; so many friends and family have reached out with words and actions of support. I knew that I was generally well liked, but I had not realized it was like this. It is both surprising and humbling, and I feel so lucky. It means a lot and I will do my best to live up to these opinions.

Anyway. A horrible thing happened to me, but I’m going to be OK, due to both incredible luck and the efforts of so many people I’ll never be able to repay.

I’m happy to answer any questions y’all have to the best of my ability.

If you liked this report, you might also like my others, though note they are significantly less dramatic:

- Trachyte Creek, Oct. 2021

- Trachyte Creek, April–May 2022

- Cheesebox Canyon, Oct. 2022

- Trachyte Creek via Woodruff Canyon, April 2023

- Ticaboo Creek, May 2024

- Cheesebox Canyon, Oct. 2024

Content warning: This report describes a life-threatening accident with serious injuries and its aftermath, though one with a known and good outcome. It’s not gory but it is candid, and I include some medical imaging of my injuries that is pretty striking.

No AI used in this report or any of my other reports.

Prologue

This photo was taken by one of the SAR (search-and-rescue) responders. It’s a detail of a larger photo of (I think) me being loaded into the helicopter that also captured something I feel is important: These individuals are having fun. My guess on the reason, having known a few folks who did SAR volunteer work and talking with them about how it works, is that they’re wrapping up a successful SAR mission at a reasonable time of day when the victim (me) was not only found alive but also conscious and oriented throughout the rescue (modulo exciting medications we’ll get to) and on his way to appropriate follow-up care. Regardless, it matters to me that my really bad day helped others have a good day.

What the accident was like

The trip started pretty normally. I drove to Bluff, UT the day before and stayed at the Recapture Lodge. Cheesebox trailhead is not far from Bluff, but this was countered by the extensive repacking I did before checking out of the hotel.I arrived at the trailhead around 11:00 AM. The area had clearly received lots of recent precipitation, for example water in the ditches alongside Highway 95 as well as actual drifts of hail in a few places. The trailhead itself had numerous puddles throughout the slickrock. However, by now the weather was great — sunny, little wind, not too warm or too cold. Occasionally, a crow would caw foreshadowingly from the junipers. After fairly extensive fooling around, I started hiking about 11:40.

My unsuspecting “before” selfie at the trailhead.

The standard route into Cheesebox follows a well-established social trail that winds northeast through a couple of cliff bands, then ledge-walks upstream in White Canyon about a half mile before descending a talus pile through the final and largest cliff band to the White Canyon wash. From there one can either ledge-walk the other side of White into Cheesebox, or follow the wash to the confluence and then climb the easy “Log Route” into Cheesebox.

I instead wanted to find my way down to the northwest, to link up with a cairn and social trail system that former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom etc. Boris Johnson and I had found a year earlier but had not been able to push to the top (see map below). There were only two unknown cliff bands really, and the first one was pretty straightforward. The second was considerably higher, but as I approached the rim, I saw a possible break corresponding to something I’d seen on the aerial photos in CalTopo. After some examination, it seemed that I could straightforwardly get about halfway down to the top of a fault filled with rubble, so if that fault also went, the whole cliff would go. I backtracked until I had a good view of the fault, which looked OK. Additionally, it seemed that I could just friction down to it, saving some backtracking.

View into White Canyon from somewhere on the descent, prior to the accident. Note the wash flowing from the precipitation.

However. Once I'd gotten down a few feet, the slope seemed sketchier than I’d anticipated — notably less grippy than I was expecting, with some sand rubbing off. The best course of action seemed to be step down to the next micro-ledge to increase stability. Unfortunately, this was not successful, and suddenly I was sliding down the slope. I had time for three thoughts: (1) “oh shit”, (2) “how is this happening to me”, and (3) “is this the end?”. Within that third thought was a pointer to a musing I’d had many times, namely: all consciousness ends, and all subjective experience is wholly internal despite our best efforts, so what value does sentience have? In particular, what is the value of sentience that is about to vanish? (E.g., clearly we value making folks comfortable at end-of-life, but why? They’re just gonna die soon.)

I was upright for a few moments, then bounced off what I assume was rubble in the fault I was heading for, which turned me 90 degrees to the left along the fault. I somersaulted down/above the rubble filling the fault an unknown number of times, and then suddenly I was staring at the sky with a thump.

Overhead photo of the White/Cheesebox confluence area. The purple line is last year’s route out, entering from the upper right and ending at the trailhead. The solid red is my actual route this time, and the dotted red is where I’d planned to continue, to link up with the known route to the canyon bottom.

Detail of the accident location. The dotted red line is how I’d intended to proceed down the rubble-filled fault to the next major ledge, then east to the known route. “Ledge approach” is the first way I thought I could get down to the fault, and I suspect SAR used this route later. “Friction approach” is where I tried and failed to get down to the fault. In magenta is the two stages of my fall and where I ended up. The cyan “haul route” is my guess on how I was extracted to the wide ledge where the helicopter was.

I think it’s worth pausing here to bring in some future knowledge, namely the actual extent of my injuries (and final content warning, this is a pretty scary list). Later in the report I have some imaging so you can see exactly what I’m talking about.

- Burst fracture of the L3 vertebra with “severe loss of ... height” and “central canal narrowing to 3mm” (yes that is where my spinal cord goes). Right transverse process (one of the bits that sticks out) of L3 also broken, but this was not displaced (i.e., the fragments not separated).

- Pelvis broken in three places on the left side. All of these were rotated and displaced. My ilium was fractured into ~3 pieces, and both the superior and inferior pubic rami were fractured.

- One of the ilium fragments was compressing the iliac vein, blocking it by about 80%. This is the same blood vessel as the femoral vein; apparently it needs a different name at a different location? It’s the huge vein that returns blood from most of the leg. Importantly, and I don’t think this was visible on the imaging, this fragment was “razor sharp” according to the surgeon, to the extent that it cut through his gloves more than once.

- Minor or moderate (I don’t know) internal bleeding within the pelvis; the hematoma later measured 19 × 11 × 3 cm.

- Sternum fracture, non-displaced.

- Left heel fracture, non-displaced. Amusingly, this wasn’t even discovered until a few days after my surgery, I’m guessing because all the other stuff was so exciting.

It wasn’t random that it was my left hip that was all smashed up. It was because I lost my grip when I had my right leg squatted under me and my left stretched out to reach the next micro-ledge. Thus, I slid down the rock in a squatting position, upright, on the sole of my right shoe, so when I collided with the rubble, it was with my left leg straight out. In principle, I might have been able to recover into a roll or something like that, instead of just hitting the ground foot first, but without practicing the move and being so surprised, I think it’s unrealistic to think and move fast enough to put it together.

I believe that’s also why the second stage was somersaulting leftward (looking down the slope) down the fault rather than stopping after the first stage: my center of gravity was well to the left of that first impact, so it started me spinning, and I hit the ledge close enough to the next drop that I continued down. I suspect that all my injuries happened in the first collision, and landing on my backpack after the second stage absorbed enough energy that I didn’t get hurt further.

According to my GPS data (specifically, trace timestamps with intervals suggesting that I was moving rather than stopped), the fall occurred at 12:12 PM, i.e. not much more than ½ hour into the hike . I did have the presence of mind to not attempt getting up right away, but rather take a few minutes to gather my wits and decide what to do. I was in an awkward position — flat on my back, slightly head down — and mighty surprised, but nothing hurt and I could move all my fingers and toes. I couldn’t find any bleeding. I could reach my water bottle and drank some water. I wriggled out of my backpack straps.

I genuinely thought that after a few minutes I’d sit up, have a snack, and be on my way with some soreness and bruises. While I was in the shade, the weather was good, the situation seemed stable and safe, the remaining distance to hike was short, and I had about six hours before dark, so there was time.

Every few minutes, I’d try to pull myself into a sitting position, but I didn’t have the leverage and couldn’t do it, even after cutting away a small amount of brush with my fancy Japanese saw. Also, I was beginning to notice a pain in my left hip that was quite mild at rest but seemed to carry great depth if I did the wrong thing — I stopped several attempts to sit up or roll not because it became painful but because I feared the pain that lurked immediately beyond (and rightly so, as we’ll see later when discussing the rescue).

First-person view of my landing spot. I recall the area as being mostly level. I don’t know if that recollection is wrong or the photo is tilted.

So, sometime around 12:40 or 12:50, I admitted to myself that I really did have a major problem and needed help. Note though that I had no idea I was hurt as bad as I was; I thought at worst it was a hip dislocation.

I activated the SOS on my InReach. I did have a flash of worry when it didn’t send right away, but I was able to reach the brain of my pack, where the device was, and clip it onto the pack waistband instead, which had a more direct view of the sky. The SOS marked itself sent at 12:58. I also sent a satellite message to my spouse so she would hear I was in trouble from me rather than somebody else. Then I started waiting.

What happens when you push the SOS button

I've run into several folks who have the same or similar device as me (Garmin inReach Messenger) and were apprehensive about what happens if they were to push the SOS button, and I worried about this too. If you push SOS accidentally, are you going to waste a bunch of people’s time and ruin your trip? Do the helicopter engines begin spooling up before your finger is even off the button?This is what my experience was. I had the device in LiveTrack mode already so it should have had a satellite fix.

- Tap the SOS button in the iOS app (there’s a physical button on the device too).

- Dialog box that says are you sure. I say yes I’m sure.

- Gaudy red full-screen 20-second countdown with a cancel button on it.

- I’m in a text chat with some customer service person from Garmin with a canned message sending from me. It's taking a little while to go, so I move the device from the pack's brain to somewhere it can see the sky better. The message sends.

- Using this chat, I communicate my situation.

Screenshots of the beginning of my conversation with Garmin. (Note: Disregard the Bluetooth warning; I made these images later when the device was turned off.)

Bottom line, IMO it would be extremely difficult to activate an SAR response accidentally.

I did observe that updating the Garmin people appeared to be a low priority for SAR once they had the information they needed, and especially once they found me, i.e., I’d guess your loved ones shouldn’t rely on Garmin for updates.

It appears that you can also schedule a test ahead of time if you’d like to actually try it.

Other important notes:

- The device seems to remain in emergency mode even after being turned off. When I plugged it in to charge five weeks later, it booted up and sent another SOS to Garmin, which we had to explain was a false alarm. It seems like you need to manually close out the emergency? That seems kind of silly since as soon as SAR got to me, I ignored Garmin, and I assume that’s typical.

- Upon receiving an SOS, Garmin will call the emergency contact you list immediately. Therefore, these contacts should be people who you want actively knowledgeable of, or ideally participating in, the response.

What being found was like

My emergency declaration sent at 12:58pm. I then hunkered down to wait, knowing that wilderness SAR response can take a long time. I figured I’d give it four hours before worrying. I received text acknowledgement from “Emergency Response” at 1:09, and by 1:12 had confirmed two-way communication as well as Garmin having notified search and rescue.My most immediate concern was hypothermia. The temperature was in the low 50s and I was presently comfortable, but I was in the shade, and if the wind picked up or I had to overnight, I might have a serious problem on my hands. I communicated this to Garmin.

I also had very limited access to my stuff, because my backpack was above and behind me, with the top opening pointing away. In particular, my jacket and sleeping bag were at the very bottom of everything. I passed the time by exploring what I did have access to and trying to get things a little organized, maybe move my pack to get into it, maybe get into a more comfortable position. None of this was particularly successful. The main tool I found was a Japanese pruning saw, and with some effort (it was not cutting the wet log I was lying on very effectively) I was able to jam some rocks and sticks under my left hip, which starting to hurt and seemed to benefit from additional support. I also found my Cheetos and ate two, though they weren't very appetizing.

My view while waiting. I’m a little annoyed this missed focus so badly because the clouds really were pretty.

Another tool that turned out quite useful was the selfie camera on my phone; I could use this to look behind me. The key item found was my pocket knife, which had exited my pocket but turned out to be within reach with a little shoving and prodding. I decided the situation was serious enough to ruin my gear and started cutting a hole in the bottom of my pack to access the jacket and sleeping bag I wanted.

Around this time, I thought I possibly heard a faint voice, though I was skeptical and concerned about wishful thinking. However, not long after, I heard a voice more clearly and yelled back, and I could even see someone across the canyon, which I though was White Canyon but perhaps just the side canyon I was descending. I decided this was good enough to believe and reported voice contact with rescuers to Garmin at 2:40, an astonishing response time of something like 1½ hours since SAR activation.

As noted above, at this point Garmin was still telling me they had no ETA. I suspect that keeping Garmin up to date is a pretty low priority for typical SAR teams.

A few minutes later there was an obvious, clear call. It occurred to me that I’d been dragging a whistle around for decades and never actually used it, and by gum it was on a pack strap that I had access to. So I responded with three whistle blasts and received back a clear and close “I’m coming!”, which I acknowledged with a single blast. Soon after that, a figure appeared at the top of the rubble crack I’d somersaulted down and asked how I was doing. I replied something notably hilarious along the lines of “been better”. I think he also asked about hitting my head and bleeding, both of which I reported negative. Then he said they were still trying to find a way down and vanished.

Finally, a boy of 12 or 13 in a San Juan County Sheriff uniform appeared in my little grove of piñons and we started chatting. He refused to move me into a more comfortable position (correctly, given my injuries), but he did get my jacket out of my pack, which helped immensely. It was a huge relief to have another human being present.

What being rescued was like

Note: All photos in this section taken by rescuers. If I learn enough for specific credits, I’ll add those.

I know the sheriff’s deputy told me his name several times over the course of the rescue, but I’ve still forgotten it. I remember vividly that the name was Polynesian (I asked), so I think of him as the Polynesian kid. Every so often during the rescue I would spot him and blurt out “Hey, it’s the Polynesian guy!” and he would laugh.

I’ll add that this part of the narrative is a bit muddled, since there was a lot going on and I kept receiving exciting drugs.

Sometime around the arrival of the Polynesian guy, a helicopter made a few passes around the area. I realized the situation may be more serious than I thought it was. I think the chopper landed and stayed put until I was ready to get on.

At some point, three more individuals arrived with me: Mark, a BLM ranger; Tom (???), an air paramedic from Classic Air Medical, who is roughly my age and gave the usual grizzled, bearded outdoorsy guy vibe; and Hannah, another air paramedic who was very clearly Gen Z and wore dramatic eye shadow. These were the four people I saw the most of. I understand the rescue was quite a bit bigger (someone told me 30 people), but the bulk of that work was happening on top of the cliff.

I worried to Mark that he wasn’t getting paid (because of the government shutdown), but apparently he was due to some exception.

Helicopter waiting. I believe the three figures at the edge of the cliff are looking down at me. According to EXIF, this photo was taken at 3:39pm.

Things started happening. Someone put in an IV. I was still cold and asked for my sleeping bag, which someone dug out of my pack via the hole I’d chopped in the bottom. That helped a lot. It was pretty clear to the paramedics that I would be a litter case. I was OK with that and said I didn’t want to be paralyzed. I was easily reassured that wouldn’t happen, though in retrospect that confidence was misplaced given my L3 burst fracture and attendant compromise of the spinal cord passage.

Hannah actually ultrasounded my pelvis. Someone brought a gadget that she plugged into her phone, and I got ultrasounded halfway up the side of White Canyon.

At some point, it became largely a waiting game as the hoist was set up and sufficient volunteers arrived. Eventually, the team agreed to sit me up, and in preparation for that I received my first dose of ketamine (and also fentanyl IIRC). Ketamine is ... not my thing. At first it was kind of cool, I just got super high and said silly high things. But once the drug really kicked in, it sucked. My vision clouded over and instead I saw a shifting field of red/yellow/orange video game type pixelated hallucinations. During this, I could hear folks talking to me and preparing to shift me into a more sitting position. When the shift came, it was still incredibly painful. I could hear myself screaming and also see the noise and pain in the video game patterns. Eventually I came down enough to start chatting with my team again and realize that I was facing a really nice canyon view instead of the sky.

Hannah offered music. I requested “Never Gonna Give You Up”. I don’t think she ever played it, though I did remind her a couple times.

I said “thank you for helping me” to people a lot.

Eventually, someone in climbing gear showed up with a litter and the actual extraction started. I got more ketamine, had another bad trip, received an excruciating, hallucinatory transfer into the litter. Apparently my inflatable sleeping pad was a useful part of this, as it was one of my few possessions that showed up in the hospital with me. Someone put a climbing helmet on me. Hannah reached out of the haze and put safety glasses on me, which for some reason felt deeply meaningful.

First stage of the hoist, up the rubble fault I’d been hoping to descent rather than somersault down. 5:24pm.

Based on rope angles in these photos, I think the ropes were re-rigged after this first stage, and I was carried across the intermediate ledges past my friction slope to a steeper part of the cliff that was more amenable to a rope extraction.

Second stage hoist. The guy on the rim at left was in charge, I think. He was talking to the litter attendant and then yelling commands behind him, and then something would happen on the rope (us moving up or whatnot). 5:36pm.

I chatted briefly with my litter attendant (Adam?) and asked where he was from, thanked him for helping me. I think I may have told him some dad jokes, which was notable to the hoist lead above because I was communicating coherently. He was busting his ass and breathing hard. The hoist wasn’t too painful overall, just when I bumped into things.

I am pretty sure the lift was done manually, i.e., a team of people yanking on the rope somehow. Sounds like hard work and I appreciate it.

Finally I was over the lip of the cliff and on top, which was a wide, spacious platform of sandstone. There was one more transfer, I believe into the helicopter’s litter. I got more ketamine for this, which I didn’t want because of the bad trips, but I was persuaded that it was better than the alternative. I was vaguely aware of being loaded into the helicopter. Coming down there was the worst; I was caught in a time loop or something and couldn’t figure out what was real. I think part of the issue was that my working memory was one or two seconds long and it was continuous, unpleasant deja vu as I rediscovered things I knew I was rediscovering. For a while, I was convinced that I was a new consciousness self-assembling from the void. I believe Hannah spent a lot of time preventing me from touching helicopter things I shouldn’t as I discovered them over and over. Sorry about that.

Helicopter departing, I think. 6:15pm.

We lifted off around sunset and flew about an hour to Grand Junction. I’m pretty sure the view was spectacular but I was too high to enjoy it.

Landing on the roof of the hospital, the usual ER stuff started. I received lots of scans and talked to my spouse about they were going to keep me overnight; apparently I sounded perturbed, like that was an overreaction. I got a preliminary inventory of my injuries. Then I was in the ICU, awaiting surgery in the morning.

Hospitalization and recovery

I was pretty messed up. Let’s take a look at my injuries.

The fly-through doesn’t show the spinal injury very well, so here are some 2-D sections. The left panel is a section of my lumbar spine viewed from my left side; note the obviously smashed L3 vertebra. The middle panel is a top-view slide of L3, and the right panel is healthy L2 (the vertebra immediately above) for comparison.

Per my orthopedic surgeon’s chart notes: “Reid needs his pelvis fixed .... It is an unusual pattern .... his hip joint is not connected to the rest of his pelvis and is malrotated and needs reduction and stability.” (Reduction just means put the bones back where they go.) He described it to me before the procedure as (paraphrasing), “Your hip joint is fine but it’s not attached to the rest of your pelvis and that’s a problem.” I really liked him.

In addition to several broken bones that needed repair in order for me to be a functional human being, there were two quite concerning swords of Damocles: (1) spinal cord at risk due to the lack of space in L3 and (2) the bone shard threatening to pierce my iliac vein. Based on later conversations, I don’t think the second risk was well understood until the surgery. To be clear, I’m not salty about this; I think it was just not visible on the imaging.

I arrived at St Mary’s at 7:29 and was transferred to the ICU at 10:30.

My initial hospital wrist band at St Mary’s. That is ... not my name. Or my birth date. Do I really look 54!?

Surgery commenced at 8:30 am on October 25 (the day after the accident) and I left the OR at 3:45 pm, i.e., 7¼ hours in surgery. I had two procedures done by different teams back-to-back: first the spinal repairs, then the pelvis. I now have 37 pieces of metal hardware in my body (my chart has an inventory).

I spent a day or two in the ICU post-surgery, then transferred to a regular floor. My sister arrived on the 26th, and then my spouse flew in on the 28th. She was able to stay for a week or so. It was the first time for our two boys that both parents were out of town at the same time, but they were champs. I’m really proud of them.

On November 8, i.e. 15 days in hospital, we finally got the logistics for transport worked out, and I transferred by ambulance to in-patient rehab at St Vincent’s in Santa Fe, which is a lot closer to home. The ride was actually pretty fun; the scenery was great and I think I yammered with the EMT not driving for three hours or so. She had a lot of interesting things to say about ketamine. Also, and this was really surprising to the EMTs, the ambulance gurney was the most comfortable I’d been since the accident.

Me in hospital at St Mary’s in Grand Junction, in the only chair I was allowed to sit in, which was incredibly uncomfortable but also a success because I could get out of bed. I assume the photo is due to the massive effort required for the transfer.

Rehab was not much fun aside from the 3 hours daily of physical therapy (PT) or occupational therapy (OT), which was hard but really productive, and the therapists liked me because my prognosis was so good. At age 46, I was the youngest person in the unit by roughly 1,000 years. I flew through rehab and came home on November 13, i.e. 6 days in rehab. Then I had one of the local visiting nurses coming by twice a week. My spouse and I went back to Grand Junction for follow-up appointments earlier this week.

First piece of mail I received after coming home.

The current status as of today, December 5, 42 days or 6 weeks after the accident, is excellent. I have minimal pain, just two rounds of acetaminophen (Tylenol) overnight. I’m getting around well by wheelchair or walker. Excitingly, I start weight bearing on my left leg tomorrow, proceeding as tolerated, so hopefully I will be walking again soon. I hope to go back to work part-time next week (I have a desk job), with the key obstacle being not my health but my employer’s bureaucracy.

There is a possibly-apocryphal story that Alfred Nobel created the Nobel Prizes because he read his own obituary. That is, Nobel’s brother Ludvig died in 1888, and at least one newspaper (which may not exist?) confused the two and printed an obituary for Alfred headlined “le marchand de la mort est mort” — “the merchant of death is dead” — including the spicy quote “Dr. Alfred Nobel, who became rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before, died yesterday.” According to the story, by reading the premature obituary, Nobel learned what people really thought of him, decided he didn’t like it, and established the Prizes in order to change that reputation before he really died.

The relevance is that for me, a key part of this accident and recovery experience is learning what people really think of me; so many friends and family have reached out with words and actions of support. I knew that I was generally well liked, but I had not realized it was like this. It is both surprising and humbling, and I feel so lucky. It means a lot and I will do my best to live up to these opinions.

Anyway. A horrible thing happened to me, but I’m going to be OK, due to both incredible luck and the efforts of so many people I’ll never be able to repay.

I’m happy to answer any questions y’all have to the best of my ability.