Curt

Member

- Joined

- Feb 1, 2014

- Messages

- 426

In Part 1 I covered covered a trip through the Northern Red Desert up to Pacific Springs on the historic Oregon Trail just west of where the Oregon Trail crossed over the Continental Divide. Part 2 picks up from Pacific Springs and follows the Oregon westward to the Pilot Butte site. From there it goes back to the eastern side of the Continental Divide and follows the path of the Oregon Trail back toward some sites in western Nebraska.

Once the Oregon Trail passed the Continental Divide the trail began to split into many sub-trails and that began almost immediately. The primary split was at "The Parting of the Ways" which is out on the prairie northeast of Farson. On Highway 28 north of Farson is a roadside exhibit to commemorate that place. The photos below are from the roadside exhibit.

In this spot the Oregon Trail ran parallel to the road. The Oregon Trail here is the wide area without sage brush. Because this area has been fenced in, no one has driven on the trail for a long time, but it's still easy to see its route.

The information panel to the left of the monument on the photo below says, “In July 1844 the California bound Stevens-Townsend-Murphy wagon train, guided by Isaac Hitchcock and 81 year old Caleb Greenwood, passed this point and continued 9 ½ miles WSW from here, to a place destined to become prominent in Oregon Trail history – the starting point of the Sublette Cut-off.

There, instead of following the regular Oregon Trail route southwest to Fort Bridger, then northwest to reach the Bear River below present day Cokeville, Wyoming, this wagon train pioneered a new route. Either Hitchcock or Greenwood, it is uncertain which, made the decision to lead the wagons due west, in effect along one side of a triangle.

The route was hazardous, entailing crossing 50 miles of semi-arid desert in the heat of summer and surrounding mountain tidges, but it saved approximately 85 miles from the Fort Bridger route and 5 or 6 days of travel. The route was first known as ‘The Greenwood Cut-off’.

It was the goldrush year of 1849 that brought this “Parting of the Ways” into prominence. Of the estimated 30,000 Fortyniners probably 20,000 travelled the Greenwood Cut-off which, due to an error in the 1849Joseph E. Ware guide book, became known as the Sublette Cutt-off.

In the ensuing years further refinements of the Trail route were made. In 1852, the Kinney and Slate Creek Cut-offs diverted trains from portions of the Sublette Cut-off, but until the covered wagon period ended, the Sublette Cut-off remained a popular direct route, and this “Parting of the Ways” was the place for crucial decisions.

A quartzite post and a Bureau of Land Management information panel now mark the historic “Parting of the Ways” site.” (Oregon-California Trails Association)

I tried to get to the actual "Parting of the Ways by driving up the "Sublette Cutoff" from the south. The Sublette Cutoff was the beginning of the Oregon leg of the split at the Parting of the Ways. The photos below show the Sublette Cutoff as it exists today. The trail in this area is on BLM land and there were no barriers to accessing it.

I got to the spot in the photo below and gave up on my attempt. This is where the Sublette Cutoff crossed the Little Sandy Creek and was the last water for 50 miles for travelers in the mid 1800'S along this route. The tracks of the Sublette Cutoff can be seen continuing up the hill on the horizon at the center of the photo.

In the photo below the Oregon Trail runs along the fence where the bridge is on the left margin of the photo. This is the route I should have taken to get to 'The Parting of the Ways' rather than trying the "Sublette Cutoff".

"This spot, where the Old Oregon Trail and Mormon Trails cross the Little Sandy River, was a popular camping and resting place for travelers headed to Oregon, California, and Utah. Indeed, this site is one of the most significant landmarks on the entire length of the trail.

Depending on the year's moisture, the Little Sandy provided the first water for emigrants and their livestock since leaving Pacific Creek, Over 20 miles east of here.

For may emigrant parties, the campsite at Little Sandy Crossing was a scene of reorganization. At the 'Parting of the Ways', 8 miles NE, many groups divided, some going to Oregon and some continuing on to Utah or California. Here, George Donner was elected Captain of the group known as the 'Donner Party' which later met a tragic end in California.

In 1824/25, William Ashley and his party of mountain men rested on the banks of the Little Sandy. In 1847, while recovering from 'mountain fever', Brigham Young, leader of the Mormon exodus from the 'States', met Jim Bridger in this area and received information about the route to Utah. In 1860, a Pony Express Station was established nearby.

"Times weren't easy for us at first because the land hadn't been farmed and there was no machinery, so we started from scratch like early settlers had done. Our first three children were raised in a little two-room log house that grandfather had built." Ruth Chesnovar (The Chesnovar family were the original owners of this place. Their descendants provided access and donated this spot so that future generations could visit it)". (Bureau of Land Management, Dept. of the Interior)

The photo below is a roadside monument placed by the Mormon Church at Farson, Wyoming a few miles from the actual location of the Little Sandy Crossing pictured above

On this hill in the photo below, the Bureau of Land Management and Wyoming Centennial Commission erected several information panels. Part of the reason for the selection of this site is because a number of Oregon Trail emigrant journals record that there were several graves at this place (none of which have been found in searches in recent years). Below I’ve copied some of the information on the panels.

“On the horizon about 25 miles to the south is Pilot Butte. An important landmark, Pilot Butte served as a guide post separating South Pass trails from the more southerly Overland Trail that crossed southern Wyoming. Oddly enough, Pilot Butte was more important to travelers headed east than it was for west-bound emigrants.

The name Pilot Butte appears on fur trade maps at least as early as 1837. Captain Howard Stansbury mentioned Pilot Butte on September 12, 1850, as his column of topographic engineers travelled east from Fort Bridger guided by Jim Bridger. Stanbury’s journal reads, “…we came in sight of a high butte, situated on the eastern side of the Green River, some 40 miles distant: a landmark well known to the traders, and called by them Pilot Butte.”

The butte grew in importance as a landmark as traffic eastward increased in the 1850’s and especially in 1862 when Ben Holladay moved his stagecoach and freighting operations from the Oregon Trail south to the Overland Route. Stand in the trail ruts immediately in front of this sign, look at Pilot Butte, and feel the passage of history.

Death was a constant companion for emigrants headed west. It is estimated that 10,000 to 30,000 people died and were buried along the trails between 1843 and 1869.

Cholera and other diseases were the most common cause of death. People didn’t know that cholera was caused by drinking contaminated water. Poor sanitation and burial practices perpetuated the disease. People infected long before might die by a river crossing and would be buried by the river which in turn would infect more people. Remedies for other ills also decreased the likelihood of survival. Amputation was often the treatment for broken bones, and bleeding the sick was often a common practice.

Accidental gunshots, drownings, murder, starvation, and exposure took their toll. The very young and the very old were the most likely to perish. Whatever the cause of death might have been for each grave passed, it was a grim reminder to the emigrant of the hazards of overland travel.

Death on the trail did not allow for the fineries of funerals back home. Emigrants made do with materials available. Black would adorn the clothes of the mourners, and care would be taken to provide the best funeral possible. The most travelers could provide was often just a shallow trench beside the trail and no coffin for the deceased. Many emigrants worried about the lack of propriety of a simple grave on the windswept prairie and vowed to return and provide a “proper” resting place.

Few of the thousands of emigrant graves have been located. The wind and snow soon obliterated any evidence of them. Markers disappeared and, in some cases, wild animals scavenged the graves. Stories of family members later returning to search for a loved one’s final resting place are common, but the searches were usually fruitless.

The official Company Journal of the Edmund Ellsworth Company of Handcart Pioneers, dated September 17, 1856 stated, “James Birch, age 28 died this morning of diarrhea. Buried on the top of a sand ridge east side of Sandy. The camp rolled at eight and travelled eleven miles. Rested…by the side of the Green River.” In the two weeks prior to Birch’s death, five other company members were buried along the trail. Birch’s gravesite has not been found. Imagine what it would be like to lose a spouse, child, or friend on the trail. You would dig a shallow grave, say your goodbyes, and continue your journey west, saddened and bereft.”

The photo below was taken at the pilot Butte site looking west and shows the Oregon Trail as it exists today winding into the distance.

From Pilot Butte I began my trip back to Nebraska following the Sweetwater valley which the Oregon trail followed after it left the North Platte River on its way to the Continental Divide. The photo below is of Split Rock. Sweetwater Creek is the green path in the foreground.

"The Sweetwater Valley contains three distinctive granite landmarks: Independence Rock, Devil’s Gate and Split Rock. The last of these, Split Rock, with its unforgettable gunsight notch, was visible to emigrants for two days or more as they approached and then left it behind them.

Some emigrants on the Oregon, California and Mormon trails—all one road at this point—found this landmark in the Rattlesnake Range a useful navigational tool as they made their way west up the Sweetwater. “[Y]esterday,” Joseph Middleton wrote in 1849, “from the time we started we steered to this cliff with a steadiness that was astonishing, never deviating from it more than the needle does from the north pole, excepting once for a short time—I think this cleft or rent or chasm is very conspicuously seen from the Devil’s Gate, which I think is 11 miles from here; and I think it is still at least 6 or 8 miles ahead. …”

Rising some 1,000 feet above the sagebrush prairie, Split Rock aimed westbound emigrants directly at South Pass, still more than 75 miles away. The relatively gentle landscape offered them a short, but much needed, respite in their long journey.

Emigrants were struck by the rock’s beauty, too. “The picture was worthy the pencil of an artist,” William Carter wrote late in 1857. “Our camp was near what is called the Split in the Rock, a remarkable cleft in the top of the mountain which can be seen at a great distance in either direction.”

Split Rock Station is located a short distance west of Split Rock between Cranner Rock and the south bank of the Sweetwater River in what is now a hay meadow. In the early 1860s, the site served as a Pony Express station, stage station and telegraph station.

Diarist Henry Herr reported that, in 1862, 50 soldiers from the 6th Ohio Regiment were encamped here to protect the emigrants. A crude log structure and pole corral that were part of the station are now part of a private ranch homesite." (wyohistory.org)

The photo below is Devil's Gate.

"A day’s travel west of Independence Rock, emigrants on the Oregon/California/Mormon trail—all one road at that point—encountered another major trail landmark: Devil’s Gate. Here, the Sweetwater River has carved a narrow cleft in the granite Sweetwater Rocks that is about 370 feet deep and 1,500 feet long. The cleft is 30 feet wide at the base but nearly 300 feet wide at its top.

Millions of years ago, sediments from eroding mountains and ash from volcanoes filled the basins between the mountains. Rivers cut indiscriminately though softer sediment and harder rock. One such cut, once the sediment again eroded away, has left Devil’s Gate.

Although the cleft was too narrow for wagons to pass through alongside the river, emigrants frequently stopped to hike around these rocks and carve their names. Often they noticed bighorn sheep climbing the hills. “The chasm is one of the wonders of the world,” emigrant Charles E. Boyle wrote in 1849. “The water rushes roaring and raving into the gorge, and the noise it makes as it comes in contact with the huge fragments of rock lying in its course is almost deafening.”

It is thought that as many as 20 emigrants are buried near here, though only the nearby 1847 grave of Frederick Fulkerson is positively known. The occurrence of several murders in this region led some emigrants to believe this truly was a bedeviled site.

One so-called legend about the origin of Devil's Gate was relayed by New Orleans newspaperman Matthew Field, who traveled up the Sweetwater in 1843. Field attributes the tale to a mixed-blood Delaware hunter, traveling with his party. The story tells of an evil beast with enormous tusks that once roamed the valley, preventing the Indians from hunting and camping. Eventually, the Indians became disgusted and decided to kill the beast. From the passes and ravines, the warriors shot the beast with a multitude of arrows. The beast, enraged, tore the cleft in the mountains with his large tusks and escaped.

By the early 1850s, trading families were running a post at Devil’s Gate and another at nearby Independence Rock. Mostly these were French-speaking men with Shoshone wives and families. Best known among them was Charles Lajeunesse, also called Simono, Seminoe or Cimoneau; the nearby Seminoe Mountains and Seminoe Reservoir are named for him. Other traders were surnamed Archambault, Perat, Papin and Mosseau. They would have traded hardware and supplies for cash or worn-out animals with the emigrants, and tools, guns and other manufactured items for buffalo robes with the tribes.

At its greatest extent, the trading post at Devil’s Gate included as many as 14 different hewn-log buildings built on three sides of a square. The structures had good floors, windows and board-and-dirt roofs. The post lay about half a mile south of where the river enters the canyon of the gate, where there was good grass for livestock and protection from the wind. Business was good—tens of thousands of emigrants were traveling the trail each year—and briefly the trading families prospered.

The Archambaults were last to run the post. They left in the summer of 1856. That fall, when two late-starting, desperate companies of Mormon handcart emigrants arrived during a terrible snowstorm, they found the post abandoned. The later company, led by Edward Martin, stopped at the post and burned part of it for warmth. Some took shelter for about a week at a cove in the rocks a mile or so upstream. Much later the cove became known as Martin’s Cove.

By 1872, a French Canadian who had anglicized his name to Tom Sun had established a hunting camp at Devil’s Gate, and by the early 1880s he and his family and cowboys were running thousands of head of cattle. The Sun family expanded the ranch steadily for more than 100 years. In the 1990s, they sold the historic core of the operation to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—the Mormons—who established a visitor center to tell the story of the stricken handcarters of 1856. The visitor center includes a reconstruction of Fort Seminoe, the 1850s trading post." (wyohistory.org)

The photo below is a picture of Martin's Cove. I had never heard of this place prior to stopping at a roadside monument. The roadside monument told a compelling story so I thought I would check things out more fully. It was fascinating to read about the tragedy that happened here. One of the most surprising things to me is that somehow Edward Martin seems to be considered a hero by Mormons. Considering that 50 people died under his charge prior to arriving here and another 100 died here, it doesn't seem to warrant hero status. His decision to compel the party to burn bedding and heavy clothing seems to be particularly short sighted (not to mention leaving Omaha in Late August to walk to Salt Lake City). The story of Martin's Cove is below. This photo was taken looking north. You can see how this spot would offer some protection from prevailing north and west winter winds. The Church of Latter Day Saints has a small retreat center nearby and maintains trails to this place. Its a decent walk from the center to this place.

"In August 1856, in Florence, Nebraska Territory (part of present day Omaha), two emigrant companies of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—the Mormons—nearly 1,100 people led by Capt. James Willie and Capt. Edward Martin, left the Missouri River to start a late-season crossing of the plains. The Willie Company left Florence on August 17, the Martin Company on August 27.

Families pushed and pulled two-wheeled, shallow-boxed handcarts, built out of green lumber a short time before. The hot sun and wind were hard on the emigrants and the handcarts. After a few weeks, the green wood began to shrink and crack. Poorly greased wooden wheels shrieked on their wooden axles.

Four months later, the survivors reached Utah Territory. On the way, more than 200 of the emigrants died, crossing what’s now Wyoming as winter set in.

The 1856 emigrants were British and Scandinavian converts en route to the new Mormon homeland in Utah. The first Mormons had arrived there and founded Salt Lake City in 1847, after a decade and a half of increasingly violent persecution in New York, Ohio, Missouri and Illinois.

By the early 1850s, most American Mormons had already arrived in Utah, and the church began actively seeking converts in Europe. Church leaders organized a smooth transit system involving chartered steamships, riverboats up the Mississippi and Missouri rivers and, later, railroad passage from the East Coast to central Iowa. Many emigrants’ passage was supported by the church.

In the mid-1850s, however, drought and famine struck Utah, and suddenly there was not nearly as much wealth in church coffers to support the incoming travelers. To save money and time, church leaders in 1856 urged emigrants use handcarts. The carts were far cheaper than wagons and ox teams, and people pulling handcarts could move more quickly when they didn’t have to wait daily for their livestock to graze.

The handcarts consisted almost entirely of green lumber and had been built in Iowa by the emigrants themselves. They were shallow, three feet wide and five feet long, and held skimpy supplies of food, plus 17 pounds of luggage—clothes, blankets, and personal possessions—for each person. A few ox-drawn wagons accompanied the party to carry tents, more food, and sick people. Rations were one pound of flour per person daily, plus any meat shot on the way. The carts were pulled by one or two people while other family members pushed behind or walked alongside.

Three smaller handcart companies had already crossed the plains to Utah quickly and successfully that year, with the help of supply wagons coming out from Salt Lake City. The crucial difference between these crossings and those of the Willie and Martin companies was timing.

Levi Savage, a sub-captain in the Willie Company wrote in his journal that he warned the party before they left Florence of "the hard Ships that we Should have to endure. I Said that we were liable to have to wade in Snow up to our knees, and Should at night rap ourselvs in a thin blanket. and lye on the frozen ground without abed…the lateness of the Season was my only objection, of leaving this point for the mountains at this time."

However, Savage’s advice was ignored. He explained, "Brother Willey Exorted the Saints to go forward regardless of Suffering even to death," and Savage was later reprimanded for "the wrong impression made by my expressing myself So freely."

The weather stayed warm. The two companies were traveling about two weeks apart. As the Martin Company reached what’s now Wyoming, food supplies were running low. To help speed the party, the captain ordered his company to reduce personal baggage from 17 to 10 pounds per person. Many people left heavy clothes and bedding, which were then burned so nobody could smuggle unauthorized items back into their carts.

Sometime in late summer, supply convoys from Salt Lake City were sent east, but failed to meet the emigrants. Records are sketchy and the reason is still unclear; it appears that these supply trains, after waiting some time for the expected handcarters, turned back when the emigrants did not show up.

But in early October, a party of fast-traveling missionaries returning to Utah from Europe, who had passed the Willie and Martin companies on the trails, arrived in Salt Lake City and reported that the two large handcart parties were still on the way. Church President Brigham Young and his counselors in Utah immediately sent relief parties in wagons well stocked with extra food, to find the latecomers and bring them in.

On October 19, the Martin Company crossed the North Platte River near present Casper, Wyo., where the trail left the river headed across country toward Independence Rock and Devil's Gate on the Sweetwater River. That day, a winter storm struck.

The water was shallow, but the river was wide and freezing cold. "[W]e had to travel in our wett cloths untill we got to camp,” emigrant Patience Loader wrote later, “and our clothing was frozen on us and when we got to camp. . .it was to late to go for wood and water the wood was to far away that night the ground was frozen to hard we was unable to drive any tent pins in. . .we stretched it open the best we could and got under it until morning."

Meanwhile, the rescuers were traveling east. On October 19, they found the stalled and starving Willie group camped in the snow on the Sweetwater River near South Pass. Half the rescue party stayed with the Willie Company. The other half pushed on, and on October 28, three scouts for the rescue party found the Martin company about 100 miles further east, at Red Buttes on the North Platte. In the nine days since the freezing river crossing, the Martin Company, exhausted and nearly out of food in the bitter cold, had moved only a few miles. One of the scouts later noted that fifty-six people in the Martin Company died during that desperate time.

Rescuer Ephraim Hanks later wrote, "the starved forms and haggard countenances of the poor sufferers, as they moved about slowly, shivering with cold, to prepare their scanty evening meal, was enough to touch the stoutest heart. . .they hailed me with joy inexpressible. . .there was only one day's quarter rations left in camp."

Hanks and the other two scouts got the Martin Company moving again 60 more miles to Devil’s Gate. There, the rest of the rescuers waited for them at some abandoned traders’ cabins called the Seminoe Fort.

Exhaustion, exposure and lack of food had weakened the emigrants of both the Willie and Martin companies, and many died even after rescue efforts had begun.

The Martin Company camped for several days in a small cove in the rocks that must have given some shelter from the wind, a mile or two east up the Sweetwater from Devil’s Gate. They still had very little food. Two small Mormon wagon trains that had been traveling close behind the large handcart company, meanwhile, arrived at Devil’s Gate about the same time. The people with these trains were also in bad shape and nearly out of food, though better off than the handcarters.

Besides personal belongings, the smaller trains were also carrying commercial freight bound for Utah. A solution became obvious: empty these trains of most of their goods, leave the goods behind at the traders’ cabins, abandon the handcarts, and give the weakest members of the Martin Company a ride the rest of the way. Twenty men stayed at Devil’s Gate to guard the wagon-train goods for the rest of the winter.

With the help of more rescue parties sent east, the Willie Company finally reached Salt Lake City on November 9 and the Martin Company on November 30. A modern historian counted 67 deaths in the Willie Company, a rate of around 14 percent, and 135 to 150 in the Martin Company, a rate of around 25 percent of the company’s members." (wyohistory.org)

I saw a lot of wildlife in this area. Below is a Sage Grouse

Long Billed Curlew

Western Meadowlark

Lark Sparrow

Two-tailed Swallowtail

Sooty Copper

Mormon Fritillary (I could be wrong with this I.D.)

Small Wood Nymph

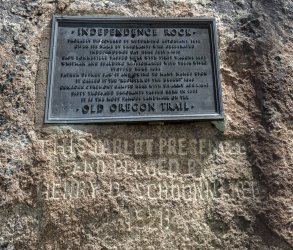

The photo below is of Independence Rock. Sweetwater Creek runs on the far side of the rock outcrop and can be seen on the right margin of the photo. The Oregon Trail was on the near side of the creek and so the entire rock was easily accessible to travelers. Inscriptions they left can be found on all sides and across the top.

"Fifty million years ago, the peaks of the Granite Range rose in today's central Wyoming, and began the long geologic processes of exfoliation. Over time, the vast weight of the mountains caused them to sag into the earth's crust, and about 15 million years ago, wind-blown sand smoothed and rounded their summits. Wind and weather eventually exposed an ancient peak, creating one of America's great landmarks.

The tribes that ranged the central Rocky Mountains — Arapaho, Arikara, Bannock, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Crow, Kiowa, Lakota, Pawnee, Shoshone, and Ute — visited the spot, and left carvings on the red-granite monolith they came to call Timpe Nabor, the Painted Rock.

The Sweetwater Valley became the main trail to the heart of the continent when American fur hunters headed west in the 1820s. As the fur trade declined, thousands of pioneers followed the roads that Indians and mountain men had blazed to the West Coast. M. K. Hugh carved the oldest recorded inscription (now weathered away) into the ancient landmark in 1824. Some say legendary mountain man Thomas "Broken Hand" Fitzpatrick named "Rock Independence" that year when he passed by on the Fourth of July. The best evidence indicates that William L. Sublette, on his way to Wind River with 81 men and 10 wagons, christened the rock in 1830, "having kept the 4th of July in due style."

Like a great stone turtle, Independence Rock sprawls over 27 acres next to the meandering Sweetwater River. More than a mile in circumference, the rock is 700 feet wide and 1,900 feet long. Its highest point, 136 feet above the rolling prairie, stands as tall as a twelve-story building.

When the pioneer priest, Pierre-Jean De Smet, saw the rock in 1841, he found "the hieroglyphics of Indian warriors" and "the names of all the travelers who have passed by are there to be read, written in coarse characters." Other sojourners called it the backbone of the universe, but De Smet dubbed the rock "the great register of the desert."

Over three decades, almost half a million Americans passed Independence Rock on their way to new homes on the frontier, and thousands of them added their names to Father De Smet's great register. Located at the approximate mid-point between the Missouri River and the Pacific Coast, Independence Rock became a milestone for travelers on the Oregon Trail. The natural wagon road up the Platte and Sweetwater rivers to South Pass became the Oregon, California, Mormon, and Pony Express roads. Wyoming lay at the heart of each of these ways to the West.

Although much of the trail has disappeared beneath modern cities and highways, hundreds of miles of nearly pristine ruts and swales still mark its course over the plains and mountains of Wyoming. Visitors at Deep Rut Hill at Guernsey, Devil's Gate, South Pass, and the Parting of the Ways can still see a landscape closely resembling the views that greeted the first sojourners. This national treasure is part of the historic legacy belonging to all Americans, and few places evoke that heritage as powerfully as Independence Rock.

The singular appearance of the formation evoked a host of descriptions. In 1832, John Ball thought the rock looked "like a big bowl turned upside down," and estimated that its size was "about equal to two meeting houses of the old New England Style." Lydia Milner Waters thought that "Independence Rock was like an island of rock on the grassy plain," while Civil War soldier Hervey Johnson reported that it looked "like a big elephant [up] to his sides In the mud."

At a distance, J. Goldsborough Bruff said the rock "looks like a huge whale." Like other goldrushers, Bruff found it "painted & marked in every way, all over, with names, dates, initials." To George Harter, Independence Rock was shaped "much like an apple cut in the middle and one half laid flat side down."

"Thousands of names are engraved, & painted by all colors of paint," wrote Daniel Budd after chiseling his name. "1 can compare it to nothing so [much] as an Irregular loaf of bread raised very light & cracked & creesed in all ways."

"Many ambitious mortals have immortalized themselves in tar & stone & paint," Charles Grey wrote in 1849. Personal glory motivated some inscribers, and topographical engineer Capt. Howard Stansbury concluded that many hoped, "judging from the size of their inscriptions, that they would go down to posterity in all their fair proportions." Amasa Morgan noted that such glory could be fleeting: "Col. Fremont's name is among the highest, but a little boy put his a little higher than the Colonel's."

"After breakfast, myself, with some other young men, had the pleasure of waiting on five or six young ladies to pay a visit to Independence Rock," one young man wrote in July 1843. He painted Mary Zachary's and Jane Mills's names high on a southeast point, but saved the best spot for himself. "Facing the road, in all splendor of gun powder, tar and buffalo greese, may be seen the name of J. W Nesmith, from Maine, with an anchor."

Except in caves and sheltered alcoves, most of the paint and tar signatures have worn away, leaving only names engraved deep in the hard granite.

Pioneers believed that the rock marked the eastern border of the Rocky Mountains. They felt well on their way if they could reach Independence Rock by the Fourth of July. Those who did often celebrated America's birthday.

Martha Hecox camped in the landmark's shadow on July 3, and "concluded to lay by and celebrate the day. The children had no fireworks, but we all joined in singing patriotic songs and shared in a picnic lunch." Polly Coon found a multitude gathered around Rock Independence on July 6, 1852. "Some one had put up a banner the 4th & it still fluttered in the breeze a happy heart cheering symbol of 'American Freedom' to the many weary toiling emigrants."

Independence Rock still overlooks the road to the West, an enduring symbol of Wyoming's contribution to our nation's colorful heritage and highest ideals." (wyohistory.org)

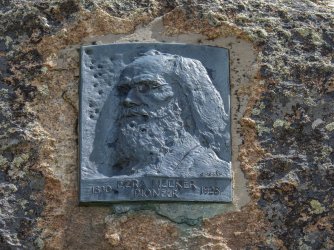

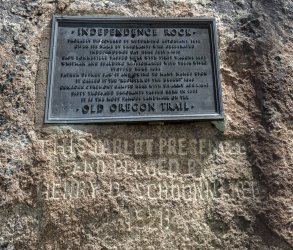

On the west side are a number of plaques.

I was surprised to see a plaque for Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spaulding. I first encountered a memorial to them at the South Pass summit which can be seen in Part 1.

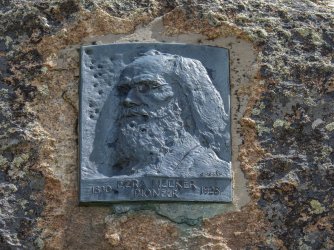

I was also surprised to see a plaque for Ezra Meeker. I also first encountered Meeker at the South Pass Summit where he erected a marker in 1906. The marker can be seen in Part 1.

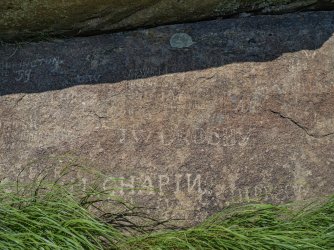

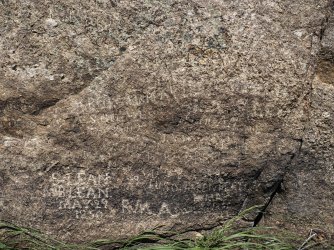

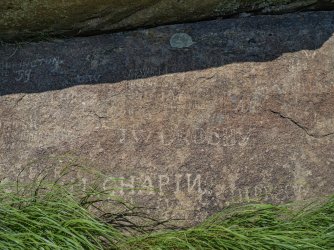

Below is the inscription that Meeker chiseled into Independence Rock in 1906. It has not stood the test of time nearly as well as the marker at South Pass summit but is still barely legible.

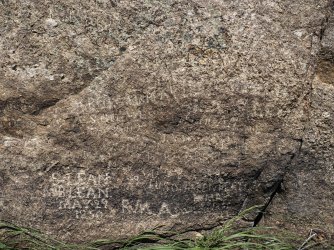

Scattered around Independence Rock are inscriptions that pioneers on the Oregon Trail left in the mid 1800's that can still be read.

One last surprise is this small cemetery at Independence Rock. I have read that for the estimated 20,000 people that died along the Oregon Trail there are only a handful of known graves.

There are a number of other Oregon Trail historical sites in eastern Wyoming but I ended up driving past them because I was trying to get to Scottsbluff in western Nebraska before dark. The photo below was taken at Scottsbluff National Monument and is probably how it would have looked in 1850 at the height of the westward migration along the Oregon Trail at Scottsbluff.

"Although earlier people did not leave very much that shows what the bluffs meant to them, evidence shows they did camp at the foot of the bluff. On the other hand, the westward emigrants of the 19th century often mentioned Scotts Bluff in their diaries and journals. In fact, it was the second most referred to landmark on the Oregon, Mormon and California trails after Chimney Rock ( a day's trip by wagon to the east). Over 250,000 people made their way through the area between 1843 and 1869, often pausing in wonder to see such a natural marvel and many remembered it long after their journeys were over.

The first Euro-Americans to see Scotts Bluff were fur traders returning to St. Louis after spending a year at the mouth of the Columbia River on the Pacific Coast. The small group of seven men was led by Robert Stuart, and on Christmas Day, 1812, he made the following entry in his journal. “21 miles same course brought us to camp in the bare Prairie, but were fortunate in finding enough driftwood for our culinary purpose. The Hills on the South have approached the river, and are remarkably rugged and Bluffy and possess a few Cedars. Buffaloe very few in numbers and mostly Bulls.” Although the Stuart party had a difficult time as the made their way eastward, the trail they blazed through present-day Wyoming and Nebraska would eventually prove to be profound historic importance for the next 60 years.

William Ashley is credited with devising a more efficient method of obtaining furs, which came to be known as the rendezvous system. Before the first rendezvous in 1827, each spring trappers would have to haul the pelts gathered the previous winter, all the way to St. Louis to sell them. Ashley's idea was to have the trappers stay out on the frontier where they could spend more time gathering pelts, ad he would bring pack trains loaded down with trade items and supplies to prearranged places. The trappers would then be able to trade their furs for items they needed and Ashley would return to St. Louis with horses loaded down with furs. The Rendezvous of 1828 led to tragic events that are now shrouded in mystery, but which would have lasting effects on Scotts Bluff. The story involves a man named Hiram Scott, an employee of the American Fur Company. It is believed that Hiram Scott was returning to St. Louis from the 1828 rendezvous when he died near the bluff which now bears his name. Unfortunately, the details surrounding his death have been lost to history.The basic story of Scott's death was first recorded by Warren A. Ferris, who traveled through the area in 1830. He related that during Scott's eastward journey, Scott had contracted a severe illness. Two comrades placed him in a boat and attempted to transport him downstream. However, for some unknown reason, the two men abandoned Scott on the north bank of the Platte River. The next spring, Scott's skeleton was found on the other side of the river, implying that he had somehow managed to cross to the opposite bank before he died. A subtle variation on this story was recorded two years later by Washington Irving. Instead of being abandoned by just two men, the ailing Scott was supposedly left behind at the Laramie Fork by a larger party who feared for their lives due to starvation. The next summer, Scott's bones were found near the bluffs - 60 miles from where he had been left to die." (National Park Service)

About 40 miles east of Scottsbluff is Chimney Rock. As the article below by the National Park Service indicates, Chimney Rock was by far the most mentioned land mark in the journals of those who had traveled on the Oregon Trail in the mid 1800's. Probably the reason for that is that this is the first landmark of any kind that the travelers would have seen for 500 miles after crossing the Missouri River as they traveled along the Platte River valley. Reportedly there were no trees growing on the banks of the Platte River as there are today and so for many weeks all that the travelers would have seen would have been a vast featureless sea of grass. This landmark also would mean that the long journey across the North American Great Plains was nearly complete and that the travelers were finally arriving at the next great challenge - crossing the Rocky Mountains. So, seeing this sight would have been momentous for anyone on the Oregon Trail. Thousands of travelers stopped to carve their names on the soft rock. Today the only names that remain are on pieces of rock that were removed long ago to be placed in museums.

"Chimney Rock is one of the most famous and recognizable landmarks for pioneer travelers on the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails, a symbol of the great western migration. Located approximately four miles south of present-day Bayard, at the south edge of the North Platte River Valley, Chimney Rock is a natural geologic formation, a remnant of the erosion of the bluffs at the edge of the North Platte Valley. A slender spire rises 325 feet from a conical base. The imposing formation, composed of layers of volcanic ash and brule clay dating back to the Oligocene Age (34 million to 23 million years ago), towers 480 feet above the North Platte River Valley.

Though the origins of the name of the rock are obscure, the title “Chimney Rock” probably originated with the first fur traders in the region. In the early 19th century, however, travelers referred to it by a variety of other names, including Chimley Rock, Chimney Tower, and Elk Peak, but Chimney Rock had become the most commonly used name by the 1840s.

After examining over 300 journal accounts of settlers moving west along the Platte River Road, historian Merrill Mattes concluded that Chimney Rock was by far the most mentioned landmark. Mattes notes that although no special events took place at the rock, it held center-stage in the minds of the overland trail travelers. For many, the geological marker was an optical illusion. Some claimed that Chimney Rock could be seen upwards of 30 miles away, and though one travelled toward the rock-spire, Chimney Rock always appeared to be off in the distance—unapproachable. Because of this optical effect, early travel accounts varied in their description of the rock. Some travelers believed that the rock spire may have been upwards of 30 feet higher than its current height, suggesting that wind, erosion, or a lightning strike had caused the top part of the spire to break off. Throughout the ages, the rock spire has continued to capture the imaginations and the romantic fascinations of travelers heading west.

Chimney Rock and its surrounding environs today look much as they did when the first settlers passed through in the mid 1800s. Erected on the southeast edge of the base in 1940, a small stone monument commemorates a gift from the Frank Durnal family to the Nebraska State Historical Society of approximately 80 acres of land, including Chimney Rock. The plot of land that the State owns provides a buffer zone to protect the historic landmark from modern encroachment. The only modern developments are Chimney Rock Cemetery, located approximately one-quarter mile southeast, and the visitor center nearby. Chimney Rock was designated a National Historic Site in 1956. The visitor center provides information on the history of the Overland Trails and Chimney Rock". (National Park Service)

A little farther east from Chimney Rock are Courthouse and Jail Rocks pictured below. Courthouse and Jail Rocks were the first rocky outcrops travelers on the Oregon Trail would have encountered on their way westward and signaled to them that they were finally approaching the Rocky Mountains after having traveled almost 500 miles across North America's Great Plains. This is about 6 miles south of the North Platte River and so, travelers typically did not come over to climb the rocks or leave their names engraved here.

“Courthouse Rock was first noted by explorer Robert Stuart in 1812 and quickly became one of the guiding landmarks for fur traders and emigrants traveling to the California, Oregon, and Utah Territories. It is a massive monolith of Brule Clay and Gering Sandstone that was likened to a courthouse or a castle. A smaller feature just to the east was called Jail Rock. From this location, Courthouse Rock has an obvious resemblance to the familiar building with a dome or cupola in the city square back home. This could be anybody’s courthouse from Maine to Iowa, but most thought it resembled the famous old courthouse in St. Louis.

While these two landmarks are located south of the North Platte River, they could be seen by the Mormons as they passed this way. Many wrote journal entries recording their fascination with land formations from Ash Hollow to Scott’s Bluff. Their journals describe the “awesome space and empty openness” as well as their interest with the rock formations that seemed to rise out of nowhere, Some called Courthouse Rock “castle like” and for some, it reminded them of a temple.

“Opposite the camp on the south side of the river is a very large rock very much resembling a castle of four stories high, but in a state of ruin, A little east a rock stands which looks like a fragment of a very thick wall. The scenery around is pleasant and romantic.” William Clayton May 24, 1847

“Meeting held at 1:15 pm at which Pres. Joseph W. Young exhorted the Saints to diligence, constancy in prayer, union, etc. Some discord having exited, he found it necessary to speak plainly to the camp and scolded them somewhat which, however, was done in an amiable spirit. At 4:45 pm the company moved on, traveled 5 miles and camped for the night at 7 o’clock on the side of the road opposite Court House Rock” Henery Pugh, clerk of the Joseph Young Company, Saturday, August 21, 1853

“Today we passed Temple Rock. This is a curious work of nature. It is a stupendous rock some eighty feet in diameter at its base. It rises some 40 feet perpendicular or nearly so. On the top of this is a dome or steeple 15 feet in diameter and 20 feet high running to a point at the top. Beside this there are smaller rocks from 15 to 20 feet high.” William Henry Branch, Sr. – Wilford Woodruff Company, Mon August 12, 1850” "

(National Park Service)

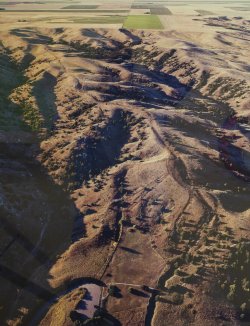

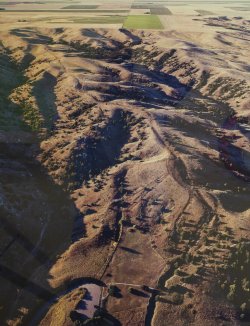

I made one more one more stop at a Oregon Trail site in Nebraska and that was at Ash Hollow State Historical Park. The photograph below is an aerial photo that hangs in the visitor center at Ash Hollow State Park. It shows the Oregon Trail ruts that ran from the South Platte River to the North Platte River. The photo is taken looking south. At the bottom of the photo is the parking lot at the base of Windlass Hill.

“Ash Hollow was famous on the Oregon Trail. A branch of the trail ran northwestward from the Lower California Crossing of the South Platte River a few miles west of Brule, and descended here into the North Platte Valley. The hollow, named for a growth of ash trees, was entered by Windlass Hill to the south. Wagons had to be eased down its steep slope by ropes. Ash Hollow with its water, wood and grass was a welcome relief after the arduous trip from the South Platte and the travelers usually stopped for a period of rest and refitting. An abandoned trapper’s cabin served as an unofficial post office where letters were deposited to be carried to the “States” by Eastbound travelers. The graves of Rachel Pattison and other emigrants are in the nearby cemetery.” (Nebraska state Historical Society)

“Windlass Hill is located along the Oregon-California Trail. The hill marked the entrance from the high table lands to the south into the Ash Hollow area and the North Platte River valley. Wagon ruts are visible on the hill. The name "Windlass Hill" was not used by the emigrants, and the source of the name is unknown. Emigrants had a hard time going down the hill at a 25-degree angle, going down for about 300 feet.” (Wikipedia)

The photograph below is another aerial photo that hangs in the visitor center at Ash Hollow State Park. The photo is taken looking north toward the North Platte River valley. Ash Hollow was a spring with a large pond and was a popular stopping spot. It is located in the center of the near trees to the right of the highway. Windlass Hill is near the center of the photo where the trail ruts drop off the ridge to the valley that crosses the highway.

Thanks for reading and looking at the photos. Hope you enjoyed the trip along the Oregon Trail.

Once the Oregon Trail passed the Continental Divide the trail began to split into many sub-trails and that began almost immediately. The primary split was at "The Parting of the Ways" which is out on the prairie northeast of Farson. On Highway 28 north of Farson is a roadside exhibit to commemorate that place. The photos below are from the roadside exhibit.

In this spot the Oregon Trail ran parallel to the road. The Oregon Trail here is the wide area without sage brush. Because this area has been fenced in, no one has driven on the trail for a long time, but it's still easy to see its route.

The information panel to the left of the monument on the photo below says, “In July 1844 the California bound Stevens-Townsend-Murphy wagon train, guided by Isaac Hitchcock and 81 year old Caleb Greenwood, passed this point and continued 9 ½ miles WSW from here, to a place destined to become prominent in Oregon Trail history – the starting point of the Sublette Cut-off.

There, instead of following the regular Oregon Trail route southwest to Fort Bridger, then northwest to reach the Bear River below present day Cokeville, Wyoming, this wagon train pioneered a new route. Either Hitchcock or Greenwood, it is uncertain which, made the decision to lead the wagons due west, in effect along one side of a triangle.

The route was hazardous, entailing crossing 50 miles of semi-arid desert in the heat of summer and surrounding mountain tidges, but it saved approximately 85 miles from the Fort Bridger route and 5 or 6 days of travel. The route was first known as ‘The Greenwood Cut-off’.

It was the goldrush year of 1849 that brought this “Parting of the Ways” into prominence. Of the estimated 30,000 Fortyniners probably 20,000 travelled the Greenwood Cut-off which, due to an error in the 1849Joseph E. Ware guide book, became known as the Sublette Cutt-off.

In the ensuing years further refinements of the Trail route were made. In 1852, the Kinney and Slate Creek Cut-offs diverted trains from portions of the Sublette Cut-off, but until the covered wagon period ended, the Sublette Cut-off remained a popular direct route, and this “Parting of the Ways” was the place for crucial decisions.

A quartzite post and a Bureau of Land Management information panel now mark the historic “Parting of the Ways” site.” (Oregon-California Trails Association)

I tried to get to the actual "Parting of the Ways by driving up the "Sublette Cutoff" from the south. The Sublette Cutoff was the beginning of the Oregon leg of the split at the Parting of the Ways. The photos below show the Sublette Cutoff as it exists today. The trail in this area is on BLM land and there were no barriers to accessing it.

I got to the spot in the photo below and gave up on my attempt. This is where the Sublette Cutoff crossed the Little Sandy Creek and was the last water for 50 miles for travelers in the mid 1800'S along this route. The tracks of the Sublette Cutoff can be seen continuing up the hill on the horizon at the center of the photo.

In the photo below the Oregon Trail runs along the fence where the bridge is on the left margin of the photo. This is the route I should have taken to get to 'The Parting of the Ways' rather than trying the "Sublette Cutoff".

"This spot, where the Old Oregon Trail and Mormon Trails cross the Little Sandy River, was a popular camping and resting place for travelers headed to Oregon, California, and Utah. Indeed, this site is one of the most significant landmarks on the entire length of the trail.

Depending on the year's moisture, the Little Sandy provided the first water for emigrants and their livestock since leaving Pacific Creek, Over 20 miles east of here.

For may emigrant parties, the campsite at Little Sandy Crossing was a scene of reorganization. At the 'Parting of the Ways', 8 miles NE, many groups divided, some going to Oregon and some continuing on to Utah or California. Here, George Donner was elected Captain of the group known as the 'Donner Party' which later met a tragic end in California.

In 1824/25, William Ashley and his party of mountain men rested on the banks of the Little Sandy. In 1847, while recovering from 'mountain fever', Brigham Young, leader of the Mormon exodus from the 'States', met Jim Bridger in this area and received information about the route to Utah. In 1860, a Pony Express Station was established nearby.

"Times weren't easy for us at first because the land hadn't been farmed and there was no machinery, so we started from scratch like early settlers had done. Our first three children were raised in a little two-room log house that grandfather had built." Ruth Chesnovar (The Chesnovar family were the original owners of this place. Their descendants provided access and donated this spot so that future generations could visit it)". (Bureau of Land Management, Dept. of the Interior)

The photo below is a roadside monument placed by the Mormon Church at Farson, Wyoming a few miles from the actual location of the Little Sandy Crossing pictured above

On this hill in the photo below, the Bureau of Land Management and Wyoming Centennial Commission erected several information panels. Part of the reason for the selection of this site is because a number of Oregon Trail emigrant journals record that there were several graves at this place (none of which have been found in searches in recent years). Below I’ve copied some of the information on the panels.

“On the horizon about 25 miles to the south is Pilot Butte. An important landmark, Pilot Butte served as a guide post separating South Pass trails from the more southerly Overland Trail that crossed southern Wyoming. Oddly enough, Pilot Butte was more important to travelers headed east than it was for west-bound emigrants.

The name Pilot Butte appears on fur trade maps at least as early as 1837. Captain Howard Stansbury mentioned Pilot Butte on September 12, 1850, as his column of topographic engineers travelled east from Fort Bridger guided by Jim Bridger. Stanbury’s journal reads, “…we came in sight of a high butte, situated on the eastern side of the Green River, some 40 miles distant: a landmark well known to the traders, and called by them Pilot Butte.”

The butte grew in importance as a landmark as traffic eastward increased in the 1850’s and especially in 1862 when Ben Holladay moved his stagecoach and freighting operations from the Oregon Trail south to the Overland Route. Stand in the trail ruts immediately in front of this sign, look at Pilot Butte, and feel the passage of history.

Death was a constant companion for emigrants headed west. It is estimated that 10,000 to 30,000 people died and were buried along the trails between 1843 and 1869.

Cholera and other diseases were the most common cause of death. People didn’t know that cholera was caused by drinking contaminated water. Poor sanitation and burial practices perpetuated the disease. People infected long before might die by a river crossing and would be buried by the river which in turn would infect more people. Remedies for other ills also decreased the likelihood of survival. Amputation was often the treatment for broken bones, and bleeding the sick was often a common practice.

Accidental gunshots, drownings, murder, starvation, and exposure took their toll. The very young and the very old were the most likely to perish. Whatever the cause of death might have been for each grave passed, it was a grim reminder to the emigrant of the hazards of overland travel.

Death on the trail did not allow for the fineries of funerals back home. Emigrants made do with materials available. Black would adorn the clothes of the mourners, and care would be taken to provide the best funeral possible. The most travelers could provide was often just a shallow trench beside the trail and no coffin for the deceased. Many emigrants worried about the lack of propriety of a simple grave on the windswept prairie and vowed to return and provide a “proper” resting place.

Few of the thousands of emigrant graves have been located. The wind and snow soon obliterated any evidence of them. Markers disappeared and, in some cases, wild animals scavenged the graves. Stories of family members later returning to search for a loved one’s final resting place are common, but the searches were usually fruitless.

The official Company Journal of the Edmund Ellsworth Company of Handcart Pioneers, dated September 17, 1856 stated, “James Birch, age 28 died this morning of diarrhea. Buried on the top of a sand ridge east side of Sandy. The camp rolled at eight and travelled eleven miles. Rested…by the side of the Green River.” In the two weeks prior to Birch’s death, five other company members were buried along the trail. Birch’s gravesite has not been found. Imagine what it would be like to lose a spouse, child, or friend on the trail. You would dig a shallow grave, say your goodbyes, and continue your journey west, saddened and bereft.”

The photo below was taken at the pilot Butte site looking west and shows the Oregon Trail as it exists today winding into the distance.

From Pilot Butte I began my trip back to Nebraska following the Sweetwater valley which the Oregon trail followed after it left the North Platte River on its way to the Continental Divide. The photo below is of Split Rock. Sweetwater Creek is the green path in the foreground.

"The Sweetwater Valley contains three distinctive granite landmarks: Independence Rock, Devil’s Gate and Split Rock. The last of these, Split Rock, with its unforgettable gunsight notch, was visible to emigrants for two days or more as they approached and then left it behind them.

Some emigrants on the Oregon, California and Mormon trails—all one road at this point—found this landmark in the Rattlesnake Range a useful navigational tool as they made their way west up the Sweetwater. “[Y]esterday,” Joseph Middleton wrote in 1849, “from the time we started we steered to this cliff with a steadiness that was astonishing, never deviating from it more than the needle does from the north pole, excepting once for a short time—I think this cleft or rent or chasm is very conspicuously seen from the Devil’s Gate, which I think is 11 miles from here; and I think it is still at least 6 or 8 miles ahead. …”

Rising some 1,000 feet above the sagebrush prairie, Split Rock aimed westbound emigrants directly at South Pass, still more than 75 miles away. The relatively gentle landscape offered them a short, but much needed, respite in their long journey.

Emigrants were struck by the rock’s beauty, too. “The picture was worthy the pencil of an artist,” William Carter wrote late in 1857. “Our camp was near what is called the Split in the Rock, a remarkable cleft in the top of the mountain which can be seen at a great distance in either direction.”

Split Rock Station is located a short distance west of Split Rock between Cranner Rock and the south bank of the Sweetwater River in what is now a hay meadow. In the early 1860s, the site served as a Pony Express station, stage station and telegraph station.

Diarist Henry Herr reported that, in 1862, 50 soldiers from the 6th Ohio Regiment were encamped here to protect the emigrants. A crude log structure and pole corral that were part of the station are now part of a private ranch homesite." (wyohistory.org)

The photo below is Devil's Gate.

"A day’s travel west of Independence Rock, emigrants on the Oregon/California/Mormon trail—all one road at that point—encountered another major trail landmark: Devil’s Gate. Here, the Sweetwater River has carved a narrow cleft in the granite Sweetwater Rocks that is about 370 feet deep and 1,500 feet long. The cleft is 30 feet wide at the base but nearly 300 feet wide at its top.

Millions of years ago, sediments from eroding mountains and ash from volcanoes filled the basins between the mountains. Rivers cut indiscriminately though softer sediment and harder rock. One such cut, once the sediment again eroded away, has left Devil’s Gate.

Although the cleft was too narrow for wagons to pass through alongside the river, emigrants frequently stopped to hike around these rocks and carve their names. Often they noticed bighorn sheep climbing the hills. “The chasm is one of the wonders of the world,” emigrant Charles E. Boyle wrote in 1849. “The water rushes roaring and raving into the gorge, and the noise it makes as it comes in contact with the huge fragments of rock lying in its course is almost deafening.”

It is thought that as many as 20 emigrants are buried near here, though only the nearby 1847 grave of Frederick Fulkerson is positively known. The occurrence of several murders in this region led some emigrants to believe this truly was a bedeviled site.

One so-called legend about the origin of Devil's Gate was relayed by New Orleans newspaperman Matthew Field, who traveled up the Sweetwater in 1843. Field attributes the tale to a mixed-blood Delaware hunter, traveling with his party. The story tells of an evil beast with enormous tusks that once roamed the valley, preventing the Indians from hunting and camping. Eventually, the Indians became disgusted and decided to kill the beast. From the passes and ravines, the warriors shot the beast with a multitude of arrows. The beast, enraged, tore the cleft in the mountains with his large tusks and escaped.

By the early 1850s, trading families were running a post at Devil’s Gate and another at nearby Independence Rock. Mostly these were French-speaking men with Shoshone wives and families. Best known among them was Charles Lajeunesse, also called Simono, Seminoe or Cimoneau; the nearby Seminoe Mountains and Seminoe Reservoir are named for him. Other traders were surnamed Archambault, Perat, Papin and Mosseau. They would have traded hardware and supplies for cash or worn-out animals with the emigrants, and tools, guns and other manufactured items for buffalo robes with the tribes.

At its greatest extent, the trading post at Devil’s Gate included as many as 14 different hewn-log buildings built on three sides of a square. The structures had good floors, windows and board-and-dirt roofs. The post lay about half a mile south of where the river enters the canyon of the gate, where there was good grass for livestock and protection from the wind. Business was good—tens of thousands of emigrants were traveling the trail each year—and briefly the trading families prospered.

The Archambaults were last to run the post. They left in the summer of 1856. That fall, when two late-starting, desperate companies of Mormon handcart emigrants arrived during a terrible snowstorm, they found the post abandoned. The later company, led by Edward Martin, stopped at the post and burned part of it for warmth. Some took shelter for about a week at a cove in the rocks a mile or so upstream. Much later the cove became known as Martin’s Cove.

By 1872, a French Canadian who had anglicized his name to Tom Sun had established a hunting camp at Devil’s Gate, and by the early 1880s he and his family and cowboys were running thousands of head of cattle. The Sun family expanded the ranch steadily for more than 100 years. In the 1990s, they sold the historic core of the operation to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—the Mormons—who established a visitor center to tell the story of the stricken handcarters of 1856. The visitor center includes a reconstruction of Fort Seminoe, the 1850s trading post." (wyohistory.org)

The photo below is a picture of Martin's Cove. I had never heard of this place prior to stopping at a roadside monument. The roadside monument told a compelling story so I thought I would check things out more fully. It was fascinating to read about the tragedy that happened here. One of the most surprising things to me is that somehow Edward Martin seems to be considered a hero by Mormons. Considering that 50 people died under his charge prior to arriving here and another 100 died here, it doesn't seem to warrant hero status. His decision to compel the party to burn bedding and heavy clothing seems to be particularly short sighted (not to mention leaving Omaha in Late August to walk to Salt Lake City). The story of Martin's Cove is below. This photo was taken looking north. You can see how this spot would offer some protection from prevailing north and west winter winds. The Church of Latter Day Saints has a small retreat center nearby and maintains trails to this place. Its a decent walk from the center to this place.

"In August 1856, in Florence, Nebraska Territory (part of present day Omaha), two emigrant companies of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—the Mormons—nearly 1,100 people led by Capt. James Willie and Capt. Edward Martin, left the Missouri River to start a late-season crossing of the plains. The Willie Company left Florence on August 17, the Martin Company on August 27.

Families pushed and pulled two-wheeled, shallow-boxed handcarts, built out of green lumber a short time before. The hot sun and wind were hard on the emigrants and the handcarts. After a few weeks, the green wood began to shrink and crack. Poorly greased wooden wheels shrieked on their wooden axles.

Four months later, the survivors reached Utah Territory. On the way, more than 200 of the emigrants died, crossing what’s now Wyoming as winter set in.

The 1856 emigrants were British and Scandinavian converts en route to the new Mormon homeland in Utah. The first Mormons had arrived there and founded Salt Lake City in 1847, after a decade and a half of increasingly violent persecution in New York, Ohio, Missouri and Illinois.

By the early 1850s, most American Mormons had already arrived in Utah, and the church began actively seeking converts in Europe. Church leaders organized a smooth transit system involving chartered steamships, riverboats up the Mississippi and Missouri rivers and, later, railroad passage from the East Coast to central Iowa. Many emigrants’ passage was supported by the church.

In the mid-1850s, however, drought and famine struck Utah, and suddenly there was not nearly as much wealth in church coffers to support the incoming travelers. To save money and time, church leaders in 1856 urged emigrants use handcarts. The carts were far cheaper than wagons and ox teams, and people pulling handcarts could move more quickly when they didn’t have to wait daily for their livestock to graze.

The handcarts consisted almost entirely of green lumber and had been built in Iowa by the emigrants themselves. They were shallow, three feet wide and five feet long, and held skimpy supplies of food, plus 17 pounds of luggage—clothes, blankets, and personal possessions—for each person. A few ox-drawn wagons accompanied the party to carry tents, more food, and sick people. Rations were one pound of flour per person daily, plus any meat shot on the way. The carts were pulled by one or two people while other family members pushed behind or walked alongside.

Three smaller handcart companies had already crossed the plains to Utah quickly and successfully that year, with the help of supply wagons coming out from Salt Lake City. The crucial difference between these crossings and those of the Willie and Martin companies was timing.

Levi Savage, a sub-captain in the Willie Company wrote in his journal that he warned the party before they left Florence of "the hard Ships that we Should have to endure. I Said that we were liable to have to wade in Snow up to our knees, and Should at night rap ourselvs in a thin blanket. and lye on the frozen ground without abed…the lateness of the Season was my only objection, of leaving this point for the mountains at this time."

However, Savage’s advice was ignored. He explained, "Brother Willey Exorted the Saints to go forward regardless of Suffering even to death," and Savage was later reprimanded for "the wrong impression made by my expressing myself So freely."

The weather stayed warm. The two companies were traveling about two weeks apart. As the Martin Company reached what’s now Wyoming, food supplies were running low. To help speed the party, the captain ordered his company to reduce personal baggage from 17 to 10 pounds per person. Many people left heavy clothes and bedding, which were then burned so nobody could smuggle unauthorized items back into their carts.

Sometime in late summer, supply convoys from Salt Lake City were sent east, but failed to meet the emigrants. Records are sketchy and the reason is still unclear; it appears that these supply trains, after waiting some time for the expected handcarters, turned back when the emigrants did not show up.

But in early October, a party of fast-traveling missionaries returning to Utah from Europe, who had passed the Willie and Martin companies on the trails, arrived in Salt Lake City and reported that the two large handcart parties were still on the way. Church President Brigham Young and his counselors in Utah immediately sent relief parties in wagons well stocked with extra food, to find the latecomers and bring them in.

On October 19, the Martin Company crossed the North Platte River near present Casper, Wyo., where the trail left the river headed across country toward Independence Rock and Devil's Gate on the Sweetwater River. That day, a winter storm struck.

The water was shallow, but the river was wide and freezing cold. "[W]e had to travel in our wett cloths untill we got to camp,” emigrant Patience Loader wrote later, “and our clothing was frozen on us and when we got to camp. . .it was to late to go for wood and water the wood was to far away that night the ground was frozen to hard we was unable to drive any tent pins in. . .we stretched it open the best we could and got under it until morning."

Meanwhile, the rescuers were traveling east. On October 19, they found the stalled and starving Willie group camped in the snow on the Sweetwater River near South Pass. Half the rescue party stayed with the Willie Company. The other half pushed on, and on October 28, three scouts for the rescue party found the Martin company about 100 miles further east, at Red Buttes on the North Platte. In the nine days since the freezing river crossing, the Martin Company, exhausted and nearly out of food in the bitter cold, had moved only a few miles. One of the scouts later noted that fifty-six people in the Martin Company died during that desperate time.

Rescuer Ephraim Hanks later wrote, "the starved forms and haggard countenances of the poor sufferers, as they moved about slowly, shivering with cold, to prepare their scanty evening meal, was enough to touch the stoutest heart. . .they hailed me with joy inexpressible. . .there was only one day's quarter rations left in camp."

Hanks and the other two scouts got the Martin Company moving again 60 more miles to Devil’s Gate. There, the rest of the rescuers waited for them at some abandoned traders’ cabins called the Seminoe Fort.

Exhaustion, exposure and lack of food had weakened the emigrants of both the Willie and Martin companies, and many died even after rescue efforts had begun.

The Martin Company camped for several days in a small cove in the rocks that must have given some shelter from the wind, a mile or two east up the Sweetwater from Devil’s Gate. They still had very little food. Two small Mormon wagon trains that had been traveling close behind the large handcart company, meanwhile, arrived at Devil’s Gate about the same time. The people with these trains were also in bad shape and nearly out of food, though better off than the handcarters.

Besides personal belongings, the smaller trains were also carrying commercial freight bound for Utah. A solution became obvious: empty these trains of most of their goods, leave the goods behind at the traders’ cabins, abandon the handcarts, and give the weakest members of the Martin Company a ride the rest of the way. Twenty men stayed at Devil’s Gate to guard the wagon-train goods for the rest of the winter.

With the help of more rescue parties sent east, the Willie Company finally reached Salt Lake City on November 9 and the Martin Company on November 30. A modern historian counted 67 deaths in the Willie Company, a rate of around 14 percent, and 135 to 150 in the Martin Company, a rate of around 25 percent of the company’s members." (wyohistory.org)

I saw a lot of wildlife in this area. Below is a Sage Grouse

Long Billed Curlew

Western Meadowlark

Lark Sparrow

Two-tailed Swallowtail

Sooty Copper

Mormon Fritillary (I could be wrong with this I.D.)

Small Wood Nymph

The photo below is of Independence Rock. Sweetwater Creek runs on the far side of the rock outcrop and can be seen on the right margin of the photo. The Oregon Trail was on the near side of the creek and so the entire rock was easily accessible to travelers. Inscriptions they left can be found on all sides and across the top.

"Fifty million years ago, the peaks of the Granite Range rose in today's central Wyoming, and began the long geologic processes of exfoliation. Over time, the vast weight of the mountains caused them to sag into the earth's crust, and about 15 million years ago, wind-blown sand smoothed and rounded their summits. Wind and weather eventually exposed an ancient peak, creating one of America's great landmarks.

The tribes that ranged the central Rocky Mountains — Arapaho, Arikara, Bannock, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Crow, Kiowa, Lakota, Pawnee, Shoshone, and Ute — visited the spot, and left carvings on the red-granite monolith they came to call Timpe Nabor, the Painted Rock.

The Sweetwater Valley became the main trail to the heart of the continent when American fur hunters headed west in the 1820s. As the fur trade declined, thousands of pioneers followed the roads that Indians and mountain men had blazed to the West Coast. M. K. Hugh carved the oldest recorded inscription (now weathered away) into the ancient landmark in 1824. Some say legendary mountain man Thomas "Broken Hand" Fitzpatrick named "Rock Independence" that year when he passed by on the Fourth of July. The best evidence indicates that William L. Sublette, on his way to Wind River with 81 men and 10 wagons, christened the rock in 1830, "having kept the 4th of July in due style."

Like a great stone turtle, Independence Rock sprawls over 27 acres next to the meandering Sweetwater River. More than a mile in circumference, the rock is 700 feet wide and 1,900 feet long. Its highest point, 136 feet above the rolling prairie, stands as tall as a twelve-story building.

When the pioneer priest, Pierre-Jean De Smet, saw the rock in 1841, he found "the hieroglyphics of Indian warriors" and "the names of all the travelers who have passed by are there to be read, written in coarse characters." Other sojourners called it the backbone of the universe, but De Smet dubbed the rock "the great register of the desert."

Over three decades, almost half a million Americans passed Independence Rock on their way to new homes on the frontier, and thousands of them added their names to Father De Smet's great register. Located at the approximate mid-point between the Missouri River and the Pacific Coast, Independence Rock became a milestone for travelers on the Oregon Trail. The natural wagon road up the Platte and Sweetwater rivers to South Pass became the Oregon, California, Mormon, and Pony Express roads. Wyoming lay at the heart of each of these ways to the West.

Although much of the trail has disappeared beneath modern cities and highways, hundreds of miles of nearly pristine ruts and swales still mark its course over the plains and mountains of Wyoming. Visitors at Deep Rut Hill at Guernsey, Devil's Gate, South Pass, and the Parting of the Ways can still see a landscape closely resembling the views that greeted the first sojourners. This national treasure is part of the historic legacy belonging to all Americans, and few places evoke that heritage as powerfully as Independence Rock.

The singular appearance of the formation evoked a host of descriptions. In 1832, John Ball thought the rock looked "like a big bowl turned upside down," and estimated that its size was "about equal to two meeting houses of the old New England Style." Lydia Milner Waters thought that "Independence Rock was like an island of rock on the grassy plain," while Civil War soldier Hervey Johnson reported that it looked "like a big elephant [up] to his sides In the mud."

At a distance, J. Goldsborough Bruff said the rock "looks like a huge whale." Like other goldrushers, Bruff found it "painted & marked in every way, all over, with names, dates, initials." To George Harter, Independence Rock was shaped "much like an apple cut in the middle and one half laid flat side down."

"Thousands of names are engraved, & painted by all colors of paint," wrote Daniel Budd after chiseling his name. "1 can compare it to nothing so [much] as an Irregular loaf of bread raised very light & cracked & creesed in all ways."

"Many ambitious mortals have immortalized themselves in tar & stone & paint," Charles Grey wrote in 1849. Personal glory motivated some inscribers, and topographical engineer Capt. Howard Stansbury concluded that many hoped, "judging from the size of their inscriptions, that they would go down to posterity in all their fair proportions." Amasa Morgan noted that such glory could be fleeting: "Col. Fremont's name is among the highest, but a little boy put his a little higher than the Colonel's."

"After breakfast, myself, with some other young men, had the pleasure of waiting on five or six young ladies to pay a visit to Independence Rock," one young man wrote in July 1843. He painted Mary Zachary's and Jane Mills's names high on a southeast point, but saved the best spot for himself. "Facing the road, in all splendor of gun powder, tar and buffalo greese, may be seen the name of J. W Nesmith, from Maine, with an anchor."

Except in caves and sheltered alcoves, most of the paint and tar signatures have worn away, leaving only names engraved deep in the hard granite.

Pioneers believed that the rock marked the eastern border of the Rocky Mountains. They felt well on their way if they could reach Independence Rock by the Fourth of July. Those who did often celebrated America's birthday.

Martha Hecox camped in the landmark's shadow on July 3, and "concluded to lay by and celebrate the day. The children had no fireworks, but we all joined in singing patriotic songs and shared in a picnic lunch." Polly Coon found a multitude gathered around Rock Independence on July 6, 1852. "Some one had put up a banner the 4th & it still fluttered in the breeze a happy heart cheering symbol of 'American Freedom' to the many weary toiling emigrants."

Independence Rock still overlooks the road to the West, an enduring symbol of Wyoming's contribution to our nation's colorful heritage and highest ideals." (wyohistory.org)

On the west side are a number of plaques.

I was surprised to see a plaque for Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spaulding. I first encountered a memorial to them at the South Pass summit which can be seen in Part 1.

I was also surprised to see a plaque for Ezra Meeker. I also first encountered Meeker at the South Pass Summit where he erected a marker in 1906. The marker can be seen in Part 1.

Below is the inscription that Meeker chiseled into Independence Rock in 1906. It has not stood the test of time nearly as well as the marker at South Pass summit but is still barely legible.

Scattered around Independence Rock are inscriptions that pioneers on the Oregon Trail left in the mid 1800's that can still be read.

One last surprise is this small cemetery at Independence Rock. I have read that for the estimated 20,000 people that died along the Oregon Trail there are only a handful of known graves.

There are a number of other Oregon Trail historical sites in eastern Wyoming but I ended up driving past them because I was trying to get to Scottsbluff in western Nebraska before dark. The photo below was taken at Scottsbluff National Monument and is probably how it would have looked in 1850 at the height of the westward migration along the Oregon Trail at Scottsbluff.

"Although earlier people did not leave very much that shows what the bluffs meant to them, evidence shows they did camp at the foot of the bluff. On the other hand, the westward emigrants of the 19th century often mentioned Scotts Bluff in their diaries and journals. In fact, it was the second most referred to landmark on the Oregon, Mormon and California trails after Chimney Rock ( a day's trip by wagon to the east). Over 250,000 people made their way through the area between 1843 and 1869, often pausing in wonder to see such a natural marvel and many remembered it long after their journeys were over.