Curt

Member

- Joined

- Feb 1, 2014

- Messages

- 426

I haven't been over to check out Backcountry Post for a while. Revisiting inspired me to post a trip from last year.

I had found a map of a road tour of Wyoming's Northern Red Desert on the internet some time ago and had wanted to do that and finally made it happen in 2023. The northern edge of the Red Desert coincides with the Oregon Trail which added some incentive. The Oregon Trail crosses my home State of Nebraska. If you live anywhere along the Platte River valley in Nebraska there are Oregon Trail historical sites. It exercises the imagination. For all the sites in Nebraska, I know that Wyoming has more and I've never visited most of them.

A lot of the places I visited on this trip are historical sites and there's a lot of info on the internet about them. I'm including some of the best I found. Some of that is long but I'm not apologizing. I hope you find it as interesting as I did. By the way, most of this trip can be done with a normal car, but the off road Oregon Trail parts should not be attempted without a high clearance 4wd vehicle.

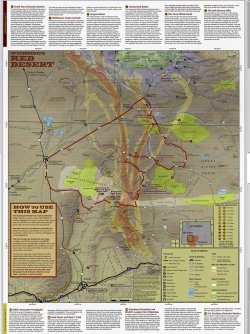

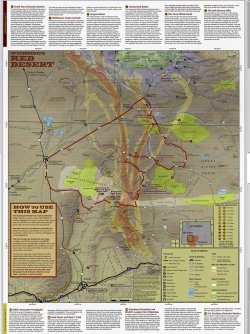

Here's the map that started me on this journey.

My first stop was at the Reliance Tipple in Reliance WY

“Coal mining operations began at Reliance in 1910. The mines were opened by the coal mining company of the Union Pacific Railroad. Here, where the tipple now stands, the first coal loading facility was constructed in 1912. The stone foundations for the earlier wooden tipple can still be seen east of the metal tipple. The current metal tipple was completed in 1936 and still contains machinery from when it was in operation. Few tipples remain from the era when coal was king. Modern mining methods and a shift to gasoline and diesel powered locomotives made underground coal mining too expensive to compete in the energy market while using the technology of the early 20th century. Tipples, such as this one, were torn down and the equipment was sold for salvage or scrap. In Wyoming, only the Reliance Tipple remains as an example of a large industrial coal handling facility. It is a silent marker of a by-gone age and serves as a tribute to the miners and their families who worked to establish homes in southwest Wyoming and to the men who lost their lives in the coal mines of Sweetwater County.” (Wyoming Centennial Commission 1890-1990)

My next stop was at The Boar's Tusk where I spent the night. The sand dunes beyond the monolith are the Killpecker Sand Dunes. It's a narrow band of active dunes that run almost 100 miles east to west.

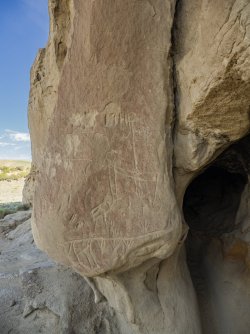

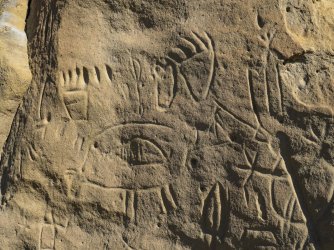

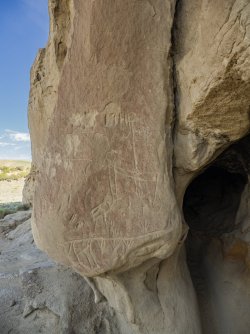

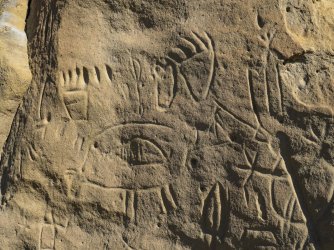

My first stop the next morning was at the White Mountain Petroglyph site.

“Hundreds of carved figures dot the sandstone cliffs at the White Mountain Petroglyphs site in Wyoming’s Red Desert north of Rock Springs. Etched into the sandstone bedrock of the Ecocene Bridger formation some 1,000 to 200 years ago, several figures appear to portray bison and elk hunts while others depict geometric forms or tiny footprints. Handprints are scooped into the rock as well, providing visitors with a compelling connection to those who used the site long ago.

The rock face also tells of contact with European cultures. Many figures portray horses, and one warrior figure is shown brandishing a sword. Members of the Shoshone, Arapaho, and Ute tribes hold this site to be sacred. Some believe this was a birthing place for Plains and Great Basin tribes.” (wyohistory.org)

Next Stop was the Crookston Ranch

“The Crookston Ranch was homesteaded by Joe Crookston around 1887 at the ever-shifting foot of the Killpecker Sand Dune Field. His family had moved to Rock Springs area from Illinois around 1870 and he had worked as a laborer as a teenager. He was 22 in 1887 when he registered his brand, “JOE” and filed his homestead paperwork. In 1908, Crookston filed his brand “row lock on a boat” and often teamed up with his brother in law, Tim Kinney, on large sheep operations.

The homestead consists of five buildings: living quarters, storage room, barns, and a foundation for an unknown building. There are also two corrals, a well, a trash dump, and a privy. The buildings are constructed from various materials that Crookston had at his disposal including a mixture of sandstone, milled lumber, logs, and adobe.

Crookston also maintained another ranch at 14 Mile that was a popular stop and saloon along the Rock Springs-Lander-South Pass Road. There are many legends associated with Butch Cassidy and his gang at 14 Mile.

Crookston died at the age of 50 in 1915. His half-brother, Richard Matthews, later bought back both of the ranches. Today, the ranch is on BLM land and can be viewed from the Killpecker Sand Dune Field. There are maintenance efforts to stabilize the buildings, but it is clear that the sand dunes are constantly getting closer to the resource. ” (Alliance For historic Wyoming)

“Crookston Ranch is a turn-of-the-century ranch. History claims Butch Cassidy would use the Crookston to rest and re-horse when on the run from the Federal Marshals.

The site is located on publicly managed land due to an error in the filing of homestead papers. The associated spring is fed by ice cells in the adjacent sand dunes. (Bureau of Land Management)

The photo below was taken looking west, but standing in this spot, looking in any direction, I could not see anything manmade except the road I was on. Strangely, this is the only place I had cellphone service over a three day period. Over that three day period I only saw a handful of people , but no one at all in this area.

The large escarpment on the right is Steamboat Mountain. To the left of that is Essex Mountain. In the center of the picture is Killpecker Sand Dunes. See below for information on the Killpecker Sand Dunes. The butte to the left of the sand dunes is North Table Mountain. To the left of it is South Table Mountain. The Continental Divide runs from the crest of Steamboat Mountain across the sand dunes to North Table Mountain. The longest mule Deer migration in North America follows the Continental Divide in this location. See below for more information on the migration.

"Arising from the southern Red Desert like a mirage, the Killpecker Sand Dunes are the largest living dune field in North America, stretching over 109,000 acres from the Green River Basin 55 miles east to the Great Divide Basin.

Ground from the granite of the Wind River Mountains by glaciers, the sand accumulated on the banks of the Big Sandy and Little Sandy Rivers downstream was blown across the continental divide by westerly winds over thousands of years. Each winter, the sand collects snow melt and windblown ice deposits, which support the vegetation that stabilizes the dunes. The collected water creates ephemeral oases in the desert that sustain a surprising array of wildlife, from migratory shorebirds to salamanders and freshwater shrimp. The dunes are also a haven for mule deer and a rare desert elk herd. Travelers may hear the sand 'sing' as sand avalanching over the crescent-shaped dunes creates a roaring, booming sound that can last for several minutes." (Citizens for the Red Desert, reddesert.org)

"The longest big game migration corridor in the lower 48 United States begins just north of Rock Springs in the Red Desert.

Twice a year, mule deer migrate between their winter range in the Red Desert sagebrush and their high elevation summer range 150 miles north in the Hoback. This one-way trip, aptly called the Red Desert to Hoback migration, allows the deer to access highly nutritious forage, essential to their health and survival, over the course of several months as the sage and grasses green up throughout the spring. Mule deer are extremely faithful to their migration routes, with herds traveling the exact same paths year after year. Recent scientific research suggests migration routes are passed down from one generation of deer to the next, in a continuous line spanning centuries." (Citizens for the Red Desert, reddesert.org)

The photo below was taken looking southeast. The western edge of the Continental Divide Basin runs from the ridge of Steamboat Mountain (right margin of the picture and behind) to the far side of the Leucite Hills (horizon on the right side of the photo) before turning east to run beyond Spring Butte and Black Rock. The elevation of the Continental Divide at Steamboat Mountain is approximately 8700 ft.

This area of Wyoming is known as 'The Red Desert'. It extends from the southern end of the Wind River Range in the north to below the Colorado border in the south. It's a little wider than the Great Divide Basin east to west covering about 15 to 20% of the State. The wild and unpopulated nature of this are may help explain why Wyoming is the least populated State in the United States with just over a half million people.

“The Great Divide Basin is the only place in North America where the Continental Divide splits into two paths creating a basin in the middle where precipitation flows neither to the Atlantic or Pacific Oceans. The Alkali Draw and Pinnacles Study Areas are visible from this spot. Alkali Draw contains rugged cliff escarpments and its springs and seeps help support several wildlife herds. The pinnacles are named for their pyramid shapes and colorful landforms. The country is some of the wildest undeveloped desert lands in the northern Rocky Mountain states.” (Citizens for the Red Desert, RedDesert.org)

The photo below is of the Tri-Territory Monument. This spot is at the intersection of the Continental Divide and the 42nd parallel. The 42nd parallel is the southern border of Oregon and Idaho and the northern border of California, Nevada, and Utah. The elevation here at the Continental Divide is 7775 feet above sea level.

“The Tri-Territory Site: Outpost of Invisible Empires

The history of America’s massive territorial expansion from the beginning of the 19th century is a complex story of treaties, purchases, annexations, compromises and conquest. At various times, Great Britain, France, Spain, Mexico and the one-time Republic of Texas all laid claim to vast territories ranging from the Mississippi River west to the Pacific—without, of course, any regard for the ownership rights of the native peoples who were already there.

On a remote sagebrush flat in Sweetwater County, Wyo., a few miles northeast of Steamboat Mountain, a simple, seldom-visited monument commemorates a place that, on maps, was once very important—though until the 1960s it was invisible. The monument marks the site on the 42nd parallel of north latitude where the boundaries of the three dominions that would make up the bulk of the American West outside of Texas all met—the Louisiana Purchase, the Oregon Territory and Mexico: the Tri-Territory Historic Site.

The Louisiana Purchase

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson’s diplomats negotiated the Louisiana Purchase with France. At a single stroke, the acquisition of 828,000 square miles at a price of $15 million nearly doubled the size of the United States. The Purchase’s eastern boundary was the Mississippi; in the West, the Continental Divide. The states carved out within its borders would come to be Missouri, Arkansas, Iowa, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska and Oklahoma in their entirety, plus most of the land in Louisiana, Colorado, Montana, Minnesota, Montana, Kansas and Wyoming.

To explore the Purchase, seek the theoretical Northwest Passage, establish an American presence in the Oregon Country, conduct scientific and economic studies and establish trade with Native American tribes, Jefferson commissioned Lewis and Clark’s epic Louisiana Purchase Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, in 1804.

For more than two years, from May 14, 1804, to Sept. 23, 1806, Capt. Meriwether Lewis, who was Jefferson’s secretary, and Lt. William Clark, the expedition’s co-commanders, led a party of five non-commissioned Army officers, 30 soldiers, and a small assortment of civilians, including the legendary Lemhi Shoshone woman Sacagawea. Theirs was a two-way, 8,000-mile journey by keel boat, canoe, on horseback and on foot from present-day eastern Missouri through what are now Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, Montana, Idaho and Oregon to the Pacific Ocean and back, with the loss of only one member of the expedition and two Blackfeet warriors.

The Oregon Country

The “Convention of Commerce between His Majesty and the United States of America,” signed in London on Oct. 20, 1818, set the boundary between the United States and British North America –what’s now western Canada—as the line of the 49th parallel of north latitude from “Lake of the Woods [in present-day northern Minnesota] to the Stony Mountains [the Rocky Mountains].” West of those mountains was the region known to Americans as the Oregon Country, while the British called it the Columbia Department. On paper, the two nations agreed on joint control over the area, but in fact the Hudson’s Bay Company, the powerful Anglo-Canadian fur trading enterprise, took serious measures to expand its business there and keep American fur traders out.

By the mid-1840s, however, the tide of American emigration to the Oregon Country along the Oregon Trail, encouraged by expansionists in Congress and elsewhere, brought steadily rising pressure on the U.S. government to remedy the situation. The result was a series of negotiations with the British, leading to the Oregon Treaty of 1846.

The treaty ended the joint occupation of the Oregon Country, setting the boundary between the United States and British North America as the 49th parallel all the way west to the Pacific, with the exception of Vancouver Island, which remained British. Those living south of the 49th parallel were declared American citizens, and those north of the line became British. Two years later, in 1848, Congress organized the American half of the region as Oregon Territory, and formed Washington Territory from it in 1853.

The southern boundary of the Oregon Country/Oregon Territory was the 42nd parallel of north latitude running from the Rockies to the Pacific; the region south of that line was Mexican territory.

Mexico and the Mexican Cession

James K. Polk of Tennessee, who served as the 11th president of the United States from 1845 to 1849, was an ardent expansionist. He was committed to Manifest Destiny, the widespread cultural belief that America was destined to expand its dominion completely across the continent to the Pacific. It was Polk who advocated the annexation of the Republic of Texas and signed the legislation making it a state in 1845, and also led the negotiations with Britain that resulted in the Oregon Treaty of 1846 and American absorption of the Oregon Country.

The Texas-Mexico border had long been the subject of a bitter dispute. In September of 1845, Polk sent John Slidell, a prominent lawyer, to Mexico City to negotiate an agreement that would settle the Rio Grande as the international boundary. Slidell also carried with him Polk’s offer to purchase California and the province of New Mexico, (which would come to encompass New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and swatches of three additional states), for a sum of up to $30 million.

When the Mexican president, José Joaquín de Herrera, refused to see Slidell, Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to occupy the disputed region between the Nueces and Rio Grande rivers and began preparing a war message to Congress. Before he could deliver it, however, he learned that Mexican cavalry had crossed the Rio Grande and attacked a small detachment of Taylor’s troops, killing 11 and capturing 52. In a quickly revised war message delivered to Congress, Polk declared that Mexico had “invaded our territory and shed American blood on American soil.” War was officially declared on May 11, 1846.

The conflict—highly controversial in the United States—ended two years later with an American victory on Feb. 2, 1848, when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed. The Rio Grande was affirmed as the southern boundary for Texas, and, for $15 million, the United States took possession of what are now California, Utah, Nevada, nearly all of Arizona, a large portion of New Mexico and significant sections of Wyoming and Colorado. This latest acquisition of some 529,000 square miles became known as the Mexican Cession.

Thus it was that by 1848, the overwhelming bulk of what would come to be known as the West was in American hands.

The Tri-Territory Historic Site

In the 1960s, the Kiwanis Clubs of Rock Springs, Lander, Riverton and Rawlins, Wyo. worked with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management to create a monument in Sweetwater County at the point where the Louisiana Purchase, Oregon Country and Mexican Cession met, at the intersection of the 42nd parallel of north latitude and the Continental Divide. The coordinates are 42 degrees north latitude, 108 degrees, 55 minutes, 1.7 seconds west longitude.

Dedicated on Sept. 24, 1967, the heart of the site is a bronze plaque mounted on a masonry monument and three flagpoles to represent Britain, Mexico and France, with a fourth atop the monument itself for the United States.

Ironically, the plaque itself later presented a problem when the site was proposed for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Writing for The American Surveyor in June 2015, Henry J. Kessner, P.E., P.S., described the situation:

There was an attempt by the Kiwanis Clubs and the BLM to include the Tri-Territory Site in the National Register of Historic Places. BLM officers vigorously pursued the proposal through the Wyoming Recreation Commission. The Commission cited two weaknesses in the BLM proposal, one of which could be corrected and another ‘which can be in no way avoided.’ The first weakness to the proposal, that which could be corrected, was the wording on the plaque which read, in part ‘...Louisiana Purchase (1803) The Northwest Territory (1846) and Mexico (1848)’. The reviewing historian, Ned Frost, correctly pointed out that ‘The Northwest Territory’ is an incorrect reference to that region of the Tri-Territory acquisitions. In all histories of the United States, ‘The Northwest Territory’ was the area that was to become the States of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and a part of Minnesota. The correct designation should be, ‘Oregon Country’. The second weakness to the proposal was that the site ‘is not in itself a place at which any historic event occurred.’ Because of these ‘weaknesses’ and other bureaucratic obstacles the nomination was vetoed. No attempt to change the wording on the plaque or to militate the other deficiencies in the nomination has to date been attempted.

No battles were fought at the Tri-Territory Site. It is miles from any emigrant trails and even farther from the railroad. It was never a settlement, nor was it a military post or a Native American encampment. Yet, for all that, its importance—and its legacy—are beyond question. It was, and will always remain, the hinge and lynchpin of the American West.

The site lies in Wyoming’s Red Desert, 28 air miles southeast of Farson and 32 air miles northeast of Rock Springs. To reach it requires more than 45 miles of travel from Rock Springs, only 10 miles of which is on a paved highway, U.S. Highway 191. The rest is on dirt roads, and a wintertime visit is not recommended.” (wyohistory.org)

"The Jack Morrow Hills, named for a 19th century crook and homesteader, run north to south between the Oregon Buttes and Steamboat Mountain and define the western edge of the Great Divide Basin. These hills are a complex of sagebrush clad ridges and rims, with seeps and drainages that provide important habitats for birds and ungulates including sage grouse, pronghorn, elk, and mule deer. The east facing slopes of Bush Rim sport a kaleidoscope of colorful sediment layers and hidden springs supporting lush groves."(Citizens of the Red Desert, RedDesert.org)

This is a picture of Continental Peak. The Honeycomb Buttes are just below. The Continental Divide passes over the top of Continental Peak and this peak along with The Oregon Buttes marks the northern end of the Great Continental Divide Basin.

This photo of the Oregon Buttes was taken a couple miles south of the Oregon Trail and is a sight that the approximately half million people who emigrated west on the Oregon Trail in the mid 1800's would have seen. Except for the addition of a few roads through this area, not much has changed since that time.

In person the Buttes seem a lot larger and can be seen for a considerable distance. The Continental Divide passes over the Oregon Buttes and marks the northern end of the Great Continental Divide Basin. The Oregon Trail passed over the Continental Divide northwest of the Buttes.

“The Oregon Buttes were a major landmark for travelers on the Oregon Trail. The name is significant because the Buttes were roughly the beginning of the Oregon Territory and also helped the emigrants be encouraged, even though there were hundreds of miles of tough going ahead. About 12 miles to the southwest of the Oregon Buttes is the location where the Oregon Territory, Mexican Territory, and Louisiana Purchase had a common boundary.” (U.S. Department of the Interior – Bureau of Land Management)

The two track road near the left margin of the photo below is the actual Oregon Trail that many thousands of people passed over in covered wagons or pushing hand carts on their way west in the mid 1800's. The butte on the left margin is Pacific Butte. A nearby Bureau of Land Management marker says this about Pacific Butte, "The great height and mass of the Butte combined with a ridge to the north paralleling the Oregon Trail created a visual channel through which travelers migrated on their way to South Pass.” (U.S. Department of the Interior – Bureau of Land Management)

That visual channel is evident as it leads to the horizon where it crosses the Continental Divide at South Pass.

The mountains on the horizon on the right side of the picture are the Wind River Range.

The photo below shows where the Oregon Trail passed over the Continental Divide. The name of this spot is South Pass. The two track road is the actual Oregon Trail. The Bureau of Land Management fenced in about 10 acres here because of the historical significance of this place. The two monuments in the foreground have been here more than 100 years. I had a copy of the USGS map loaded on my phone and, zoomed in all the way, it appears that the contour line for the Continental Divide passes between the monuments. It was pleasing to see that neither monument has been shot or vandalized in any way. It probably helps that this place is somewhat remote and a little hard to get to. Even though it seems very nondescript, standing on the Oregon Trail looking at the monuments I felt an eerie feeling of the flow of history thinking about the half million people that passed this spot in covered wagons 170 years ago, what motivated them to cross 2000 miles of wilderness, and the hardships they endured doing it. Perhaps I'm not the only one who felt that and possibly that's part of the reason why the monuments have been respected.

The photo was taken looking eastward after the storm in the previous photo had passed. I'll have more information about this place and the monuments in subsequent photos.

“Even after the rediscovery of South Pass in 1824, it was years before the route was used extensively. Fur trapper/trader William Sublette brought a small caravan of wagons to South Pass in 1828. While his party did not take wagons over the pass, they demonstrated the feasibility of using them. Captain Benjamin Bonneville took the first wagons over South Pass in 1832. But it was U.S. Government explorer, Lt. John Charles Fremont, who was responsible for publicizing the South Pass route. Scattered references to an easy passage over the Rockies had appeared in newspapers for a decade, but in 1842 Fremont created enthusiasm for South Pass by explaining that a traveler could go through it without any “toilsome ascents”. As knowledge of South Pass became widespread, a great western migration commenced. Thousands of Mormons, and future Oregonians and Californians, would cut a wide swath along the route in the next twenty years.” (U.S. Department of the Interior – Bureau of Land Management)

This photo was taken a while after the previous photo and is looking west. Again, the two track road is the actual Oregon Trail, the route of the western expansion of the U.S. in the mid 1800's.

“Even after the rediscovery of South Pass in 1824, it was years before the route was used extensively. Fur trapper/trader William Sublette brought a small caravan of wagons to South Pass in 1928. While his party did not take wagons over the pass, they demonstrated the feasibility of using them. Captain Benjamin Bonneville took the first wagons over South Pass in 1832. But it was U.S. Government explorer, Lt. John Charles Fremont, who was responsible for publicizing the South Pass route. Scattered references to an easy passage over the Rockies had appeared in newspapers for a decade, but in 1842 Fremont created enthusiasm for South Pass by explaining that a traveler could go through it without any “toilsome ascents”. As knowledge of South Pass became widespread, a great western migration commenced. Thousands of Mormons, and future Oregonians and Californians, would cut a wide swath along the route in the next twenty years.” (U.S. Department of the Interior – Bureau of Land Management)

The photo below is a composite. The foreground photo was taken looking ENE and is my first attempt using 'Low Level Lighting'. I had an LED panel with me and set it up about 30 yards behind me to the right. I set it at 1% of it's available brightness. It still seemed bright in the darkness. The Milky Way photo was taken looking south. The northern 1/3 of the sky was overcast but I was still able to see Polaris so I set up my star tracker and used that for the sky photo. The light pollution on the horizon on the left is from Rock Springs which was about 50 miles away by line of sight. The light pollution on the right is from Farson which was about 30 miles away.

“Without South Pass, the entire history of the United States’ expansion west of the Mississippi would have been different. South Pass got its name to distinguish it from the tedious and difficult northern route through the Rocky Mountains taken in 1805 and 1806 by Lewis and Clark through the Bitterroot Mountains.

As any aficionado of the Corps of Discovery knows, the Bitterroots nearly destroyed the dreams of that expedition. By the time the Corps stumbled out of the mountains, they were frozen and near death from starvation. Even today, few roads cross the Bitterroots, and the country between the great Missouri River and the mighty Columbia remains as topographically complicated as it was when Lewis and Clark crossed it.

Thus, the discovery of a direct land route across the Continental Divide with a relatively easy grade was a godsend to those who hoped to see the United States of America stretch from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Without South Pass, it is almost certain that the Pacific Northwest would have been permanently claimed by the British and the southern part of the continent would have remained part of Mexico. South Pass, the isolated little saddle that straddles the Continental Divide in the midst of Wyoming, still the least populated state in the nation, truly provided the key to today's United States.

While the pass had been used by American Indians for millennia, the first known usage by white men occurred in 1812 when Robert Stuart and six companions crossed the mountains on their return to the East from Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia, on the Oregon coast. In 1832, Capt. Benjamin Bonneville and a caravan of 110 men and 20 wagons became the first group to take wagons over the pass.

Then, on July 3, 1836, missionary Marcus Whitman crossed the pass with his wife, Narcissa, and their missionary companions, Henry Spalding and Eliza Hart Spalding. Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Hart Spalding became the first white women to cross the Continental Divide at South Pass.

This tiny trickle of white people would become a stream in the 1840s and a river in the 1850s and 1860s. Between 1841, when the first Oregon-bound wagon train was organized, and 1869 when the transcontinental railroad was completed, somewhere between 350,000 and 500,000 emigrants crossed South Pass on the trails bound for Oregon, California or Utah’s valley of the Great Salt Lake. Their multiple routes converged to form a common trail corridor near Fort Kearny in what’s now central Nebraska before parting again beyond Dry Sandy, a short way west of South Pass.

As the years went by, commercial freight traffic, bound east as well as west, became steadily more common on the route across South Pass. The 1850s saw stagecoaches carrying passengers and mail offering first monthly, then weekly and finally daily service.

The Pony Express was established in the spring of 1860, and at its inception could carry a letter from St. Joseph, Missouri via South Pass to Sacramento, California in just two weeks. Construction of a transcontinental telegraph line began about the same time along the same route; by the fall of 1861 the line was finished and the Pony Express disbanded.

After 1862, much of the commercial traffic moved south to the Overland Trail, which crossed what’s now southern Wyoming by a more direct route, most of which later became the route of the Union Pacific Railroad and Interstate 80. The telegraph continued to follow the South Pass route until the late 1860s, when it was moved south to the railroad line.

For westbound travelers, the push to the South Pass crossing started at Independence Rock, where their slow, steady climb over the Continental Divide began. Many didn't even realize the backbone of the Rockies had been conquered until they reached Pacific Springs west of the pass, so gradual was the incline.

And the exact elevation of that backbone has been disputed throughout modern times. Today, it is fairly well established that the crest of South Pass is situated on the Continental Divide in Fremont County, Wyo., about 10 miles southwest of South Pass City, at 42 degrees 21 minutes north latitude and 108 degrees 53 minutes west longitude, at an elevation of 7,440 feet above sea level, or 2,267.712 meters.

Until recently, however, there was a surprising amount of confusion about the elevation. The noted historian, Dale L. Morgan, gave its elevation as 7,550 feet above sea level, a figure that has often been cited though it actually reflects the elevation of the Continental Divide to the north of the pass. The U.S. Geological Survey’s Pacific Springs 7.5 minute quadrangle gives the elevation as 7,412 feet, as do many other reference works.

During a June 2006 field survey, Colleen Sievers of the U.S. Bureau of Land Management’s Rock Springs office took a Global Positioning System reading at the Meeker and Whitman monuments, normally considered to be "the summit," that produced a reading of 7,440 feet above average mean sea level, with an error factor of plus or minus three feet.

Trail expert Paul Henderson wrote of the Meeker marker, "This monument stands twenty feet west of the actual culminating height of the Pass where the old trail crossed the divide line," but did not explain how he determined that location. According to another well-known trail expert, Gregory Franzwa, the U.S. Geological Survey engineers surveying the Continental Divide in 1946 determined that Ezra Meeker--the pioneer promoter of preserving Oregon Trail history— missed "the precise location of the divide . . . by less than fifty feet."

Today, most people view the pass from the BLM's roadside exhibit, situated just off state Route 28. From there, it is possible to follow the old trail ruts next to the exhibit parking area to the actual summit which you will know you have reached, even without a GPS unit, by the two markers you will find there.

At South Pass, visitors can still imagine themselves as fur trappers, trailblazers, missionaries or emigrants bound for Oregon, forty-niners eager for California gold or recently converted Mormons, just arrived from Scandinavia.

The West opens up for anyone who stands on South Pass.” (wyohistory.org)

Regarding the OLD OREGON TRAIL Meeker marker; “Located at the summit of South Pass, the simplicity of this marker belies its significance in preservation of the Oregon Trail. The marker was placed there in 1906 by Ezra Meeker. Earlier, in 1852, Meeker and his wife had made their way from Ohio to Oregon Territory on the trail. To him the Oregon Trail was a “symbol of the heroism, the patriotism, the vision, and the sacrifice of the pioneers who had won the West for America” and in 1906 he began an effort to mark significant spots along the Trail. Until then there were only twenty-two monuments on the 2000 mile route.

Meeker’s campaign took the form of traveling from Puget Sound to Independence Missouri (west to east) by covered wagon pulled by oxen. Beginning in March, he reached South Pass in mid-June where he erected the marker above. In his book, Ox-Team Days he described the event.

'On June 22 we were still camped at Pacific Spring. I had searched for a suitable stone for a monument to be placed on the summit of the range, and after almost despairing of finding one, had come upon exactly what we wanted. The stone lay alone on the mountain side; it is granite, I think, but mixed with quartz, and is a monument hewed by the hand of Nature.

… With the help of four men we loaded the stone, after having dragged it on the ground and over the rocks a hundred yards or so down the mountain side. We estimated its weight at a thousand pounds.

… The letters were then cut out with a cold chisel, deep enough to make a permanent inscription. The stone was so hard that it required steady work all day to cut the twenty letters and figures.' ” (TheHistoricalMarkerDatabase.org)

Regarding the Narcissa Whitman - Eliza Spalding marker; "Captain H.G. Nickesron, president of the Wyoming Oregon Trail Commission, chiseled this sign and many others like it between 1913 and 1921. He wrote in a letter, "It took me two days to cut 80 letters in the Whitman-Spalding stone." (TheHistoricalMarkerDatabase.org)

“A love of adventure may have drawn many of the young men attracted to the fur trade and "a life more wild and perilous," as Francis Parkman put it, but the driving force behind the first American presence in the Rocky Mountains was purely economic: Without the fortunes that could be made in the fur trade, there was nothing to attract Americans to such a strange, distant and dangerous country. Once the mountaineers and the fur companies eliminated the region’s beaver population, there appeared to be nothing left to induce any rational person to live there.

Mapmakers labeled the region "the great American desert." Americans who had seen the Rocky Mountains expressed an even lower opinion of the region’s potential. After a hard march to the fur-trade rendezvous in 1834, William Marshall Anderson found the face of the country from the North Platte River at the Red Buttes to his camp on the Big Sandy west of South Pass "barren in the extreme; it is sand and nothing but sand." It was one immense desert, "a true American 'Sahara,'"

Only something as unexpected as the discovery of a new source of wealth or as compelling as economics seemed capable of altering this reality. That force was power of religious faith, and it ultimately inspired more enduring consequences than the struggle to control the fur trade in the Rocky Mountains.

That transformative power arrived in the form of three missionaries who set out for Oregon in 1834 under the command of a broad-shouldered former Yankee lumberjack. Ironically, it was a request from natives of the Pacific Northwest that set these events in motion. In October 1831, fur trader Lucien Fontenelle brought four Salish and Nez Percé emissaries from the Oregon Country to meet with Indian Superintendent William Clark in St. Louis, who had first seen their country when he crossed the Rocky Mountains with Meriwether Lewis and the Corps of Discovery, decades before.

Clark understood that they had come to ask for someone to teach their people about the white man’s powerful book, which Clark interpreted as a request for a minister to explain the Bible. An account of the request appeared in the Methodist Christian Advocate in March 1833, which issued the call, "Let the Church awake from her slumbers and go forth in her strength to the salvation of these wandering sons of our native forests." Dr. Wilbur Fisk asked the Methodist Mission Board to send missionaries to answer the request, and the board provided $3,000 to fund the effort. Fisk recommended a former pupil at the Wilbraham Academy to lead the effort, and the Rev. Jason Lee was called to Oregon.

Along with several naturalists and adventurers, Lee, two more missionaries, and two hired hands joined Massachusetts fur trader Nathaniel Wyeth’s second venture to the West to deliver supplies to the Rocky Mountain Fur Company in spring 1834. Lee and his companions were the vanguard of a small but devoted band of Christian evangelists who accomplished something that had seemed entirely impossible.

In 1835, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) sent the Rev. Samuel Parker on what he called "an exploring mission" to Oregon to evaluate "the condition and character of the Indian nations and tribes, and the facilities for introducing the gospel and civilization among them." Parker set out for the far West on 22 June 22 with the American Fur Company’s supply caravan.

Assisting Parker was his young associate, Dr. Marcus Whitman, a man "of easy, don’t care habits, that could become all things to all men, and yet a sincere and earnest man, speaking his mind before he thought about it the second time," as William H. Gray, a carpenter Whitman hired to go west with him in 1836, recalled years later. As Gray observed, when he set his mind to doing something, Whitman was capable of unflinching tenacity. When Whitman made the journey again, in 1836, he was accompanied by his new bride, Narcissa Prentiss.

They crossed South Pass on July 3, 1836. The next day, July 4, the group stopped near Pacific Springs, knelt down, and with Bible and the American flag in hand, claimed the Pacific coast for their native country. Henry Spalding recorded: "The moral and physical scene was grand and thrilling. Hope and joy beamed on the face of my dear wife, though pains racked her frame. She seemed to receive new strength. 'Is it reality or a dream,' she exclaimed, 'that after four months of hard and painful journeyings I am alive, and actually standing on the summit of the Rocky Mountains, where yet the foot of white woman has never trod?'"

When they crossed South Pass, the missionaries Eliza Spalding and Narcissa Whitman "were in the vanguard of a great procession of men, women and children, who were to travel that same way" over the next three decades, wrote historian Clifford M. Drury. "They proved it was possible for women to cross the Rockies."

Whitman and Spalding showed that women could meet whatever challenges the West could throw at them, and if there were any remaining doubts, the next four American women to ride to Oregon on horseback—missionaries Myra Fairbanks Eells, Mary Richardson Walker, Mary Augusta Dix Gray and Sarah Gilbert White Smith—dispelled them in 1838.” (wyohistory.org)

It is worth taking some time to google these two ladies and read about their lives. Narcissa lived a tragic life. She had a baby, her only child, the year after making the trek to the west coast. He drown in a creek when he was two years old. She was murdered in 1847. Eliza Spalding also knew some heartache losing her first child who was still born the year after making the trek across the continent. But she had 4 more children by 1847 and adopted several more. She died of tuberculosis in early 1851.

This is what the Oregon Trail looks like today west of South Pass. The State of Wyoming has placed markers about every mile along the trail in this area.

In the photo below I believe that the building on the right is the store mentioned below. Also, the middle building is the remains of the 2 story barn mentioned in the story below

“The town of Pacific Springs was once called the “Old Halter and Flick Ranch”. This unique town, founded in 1853, is referred to by old-timers as the “muddiest damn spot on the Lander-Rawlins Stage Road”.

It is indeed muddy! Situated on a swampy flat at an elevation of 7200 feet, the waters of Pacific Springs meander about, sending fingers of water in all directions. During the spring rains, the main street was unsafe, and it was the only street in town.

Although eight of its buildings have been moved away, five structures remain. The romance of a very old and deserted town is still present. A livery or two-story barn is on the north side, complete with eight double stalls. It was once used to provide shelter for relay horses on the stage and Pony Express lines.

The old Pacific Springs store is intact, but does not display the expected false front. The town was built before such refinements became commonplace. The store has long since been converted to a storage house for a nearby ranch.

Two residences and a log soddy complete the remains of what was once a celebration spot on the Oregon Trail.

This site marked the first camping spot on for emigrants after crossing South Pass. The pass is only 7400 feet high but is subject to severe storms in early and late summer. Many travelers celebrated the evening of the crossing only to wake up and face the double hazard of a hangover – and three miles of mud. By 1918 the town had faded to just a post office named Pacific.” (‘Ghost Towns of the Northwest’ by Norm Weis)

The photo below is Pacific Springs. On the right margin of the picture are the remains of the old Halter and Flick Ranch - also known as the ghost town of Pacific Springs. The photo was taken from the ruts of the Oregon Trail. The mountains on the horizon are the Wind River Range.

“Pacific Springs—an extensive marsh in a bleak, dry landscape—is in a low place just west of South Pass. For emigrants on the Oregon Trail, it was the first source of good water after crossing the Continental Divide. From the east-flowing rivers and streams they had followed for so many miles, the pioneers had finally arrived at water that would end up in the Pacific Ocean.

Isaac Wistar, in his June 30, 1849, diary entry, captures a sense of the magnitude of this transition. “With three cheers and several more, we rolled on downward toward the setting sun, not forgetting to carry a little water destined by nature for the Atlantic, to be poured into the first west-flowing water for transfer to the western ocean.”Clearly filled with wonder, he adds, “How near together the solitary mountain sources of these little streams, and yet with half the world between them, how widely severed their ultimate destinations!”

Like Wistar, Patrick McLeod and his company were traveling in 1849, the first of the several years when, thanks to the California Gold Rush, emigrant traffic was the heaviest ever seen on the trails. “We had great difficulty in finding a camping place,” he wrote on July 4 of that year. “[A]ll round the springs was covered with camps, and even if such had not been the case the grass was so poor and growing in an alkali bottom we would scarcely have camped near them. Indeed the number of dead oxen was so great, that the gasses arising from their putrefying bodies rendered it very disagreeable to the olfactory nerves.”

Next summer the trail was crowded again and commerce had sprung up to serve the horde. James W. Evans wrote on June 28, 1850, “At the spring a Yankee of the Barnum school had turned his carriage around as if he were going back. A large placard announced the pleasing fact that it was an Express wagon to carry letters back to the States!” He and others were glad to have this unexpected way to tell their families they were safe, and where they were. “Who among this vast emigration did not avail himself of this opportunity of writing a few lines back to their parents, or to their wives, to announce the fact that they were astraddle of the Rocky Mountains! I for one did and I saw many with tearful eyes and with a hand trembling with emotion, tracing a few short lines to their loved ones at home. The price for the transmission of each letter was fifty cents.”

Franklin Langworthy noticed that people were not just traveling in covered wagons. On June 29, 1850, he wrote, “While here, a fine train of sixteen splendid carriages overtook and passed up. It was one of the passenger trains from the city of St. Louis, which takes passengers from that place to California, for the sum of two hundred dollars.”

Two years later, there was still significant traffic, and sometimes the wagons stopped long enough for socializing. On July 25, 1852, John N. Lewis wrote, “[T]here was about 100 wagon here & we got the girls together & had a fiddle & catarrh [probably “guitar”] & fine girls & another such a party was never got up all for Oregon.

“[W]e had no house to dance in,” Lewis notes. “We took it on the ground. The moon was shining bright & the dust could be seen rising over the party for 2 hundred yards.”

Others were less cheerful and energetic. Feed for their stock was scarce. “Went to the springs and found it all eaten away there and even below,” wrote Andrew S. McClure on July 7, 1853. McClure also noted the hazards which time and heavy traffic had not affected. The springs “are seeps which supply a marsh, which is very dangerous to stock as it is very miry and stock which has come through is apt to be hungry and dash headlong into the marsh, from whence some never return.”

About two weeks later, on July 23, Rebecca Ketcham found Pacific Springs “dreary … [and] gloomy-looking,” adding, “When there was a dry spot it had been camped on and was covered with manure and other filth.”

By 1860, there was a rudimentary post office and newsstand. Allen Tyrrell’s July 6 diary entry from that year states, “A log mail-station stands near the springs. I stopped in for a few moments. Noticed a N.Y. Ledger there among other papers.”

The marsh, apparently an enduring feature of Pacific Springs, was still there when James Yager arrived on June 30, 1862. Like others before him, Yager could shake the boggy ground “for several yards around.” Yager was also filled with the wonder of having crossed the divide. “[O]n the same day, on the same morning & within a space of two hours I drank of the Pacific & Atlantic.”

In the 1860s, a stage and Pony Express station existed in this area, probably near the Halter and Flick Ranch. It was apparently burned by the Indians in 1862. Its exact location is unknown. There are several graves in this area.” (wyohistory.org)

Brewer's Sparrow

Sage Thrasher

Mourning Dove

Yellow Warbler

Yellow-bellied Sapsucker

Western Wood Pewee

Blue Copper

Northern Checkerspot

Coronis Fritillary (I could be wrong about that I.D.)

Rocky Mountain Parnassian

I had found a map of a road tour of Wyoming's Northern Red Desert on the internet some time ago and had wanted to do that and finally made it happen in 2023. The northern edge of the Red Desert coincides with the Oregon Trail which added some incentive. The Oregon Trail crosses my home State of Nebraska. If you live anywhere along the Platte River valley in Nebraska there are Oregon Trail historical sites. It exercises the imagination. For all the sites in Nebraska, I know that Wyoming has more and I've never visited most of them.

A lot of the places I visited on this trip are historical sites and there's a lot of info on the internet about them. I'm including some of the best I found. Some of that is long but I'm not apologizing. I hope you find it as interesting as I did. By the way, most of this trip can be done with a normal car, but the off road Oregon Trail parts should not be attempted without a high clearance 4wd vehicle.

Here's the map that started me on this journey.

My first stop was at the Reliance Tipple in Reliance WY

“Coal mining operations began at Reliance in 1910. The mines were opened by the coal mining company of the Union Pacific Railroad. Here, where the tipple now stands, the first coal loading facility was constructed in 1912. The stone foundations for the earlier wooden tipple can still be seen east of the metal tipple. The current metal tipple was completed in 1936 and still contains machinery from when it was in operation. Few tipples remain from the era when coal was king. Modern mining methods and a shift to gasoline and diesel powered locomotives made underground coal mining too expensive to compete in the energy market while using the technology of the early 20th century. Tipples, such as this one, were torn down and the equipment was sold for salvage or scrap. In Wyoming, only the Reliance Tipple remains as an example of a large industrial coal handling facility. It is a silent marker of a by-gone age and serves as a tribute to the miners and their families who worked to establish homes in southwest Wyoming and to the men who lost their lives in the coal mines of Sweetwater County.” (Wyoming Centennial Commission 1890-1990)

My next stop was at The Boar's Tusk where I spent the night. The sand dunes beyond the monolith are the Killpecker Sand Dunes. It's a narrow band of active dunes that run almost 100 miles east to west.

My first stop the next morning was at the White Mountain Petroglyph site.

“Hundreds of carved figures dot the sandstone cliffs at the White Mountain Petroglyphs site in Wyoming’s Red Desert north of Rock Springs. Etched into the sandstone bedrock of the Ecocene Bridger formation some 1,000 to 200 years ago, several figures appear to portray bison and elk hunts while others depict geometric forms or tiny footprints. Handprints are scooped into the rock as well, providing visitors with a compelling connection to those who used the site long ago.

The rock face also tells of contact with European cultures. Many figures portray horses, and one warrior figure is shown brandishing a sword. Members of the Shoshone, Arapaho, and Ute tribes hold this site to be sacred. Some believe this was a birthing place for Plains and Great Basin tribes.” (wyohistory.org)

Next Stop was the Crookston Ranch

“The Crookston Ranch was homesteaded by Joe Crookston around 1887 at the ever-shifting foot of the Killpecker Sand Dune Field. His family had moved to Rock Springs area from Illinois around 1870 and he had worked as a laborer as a teenager. He was 22 in 1887 when he registered his brand, “JOE” and filed his homestead paperwork. In 1908, Crookston filed his brand “row lock on a boat” and often teamed up with his brother in law, Tim Kinney, on large sheep operations.

The homestead consists of five buildings: living quarters, storage room, barns, and a foundation for an unknown building. There are also two corrals, a well, a trash dump, and a privy. The buildings are constructed from various materials that Crookston had at his disposal including a mixture of sandstone, milled lumber, logs, and adobe.

Crookston also maintained another ranch at 14 Mile that was a popular stop and saloon along the Rock Springs-Lander-South Pass Road. There are many legends associated with Butch Cassidy and his gang at 14 Mile.

Crookston died at the age of 50 in 1915. His half-brother, Richard Matthews, later bought back both of the ranches. Today, the ranch is on BLM land and can be viewed from the Killpecker Sand Dune Field. There are maintenance efforts to stabilize the buildings, but it is clear that the sand dunes are constantly getting closer to the resource. ” (Alliance For historic Wyoming)

“Crookston Ranch is a turn-of-the-century ranch. History claims Butch Cassidy would use the Crookston to rest and re-horse when on the run from the Federal Marshals.

The site is located on publicly managed land due to an error in the filing of homestead papers. The associated spring is fed by ice cells in the adjacent sand dunes. (Bureau of Land Management)

The photo below was taken looking west, but standing in this spot, looking in any direction, I could not see anything manmade except the road I was on. Strangely, this is the only place I had cellphone service over a three day period. Over that three day period I only saw a handful of people , but no one at all in this area.

The large escarpment on the right is Steamboat Mountain. To the left of that is Essex Mountain. In the center of the picture is Killpecker Sand Dunes. See below for information on the Killpecker Sand Dunes. The butte to the left of the sand dunes is North Table Mountain. To the left of it is South Table Mountain. The Continental Divide runs from the crest of Steamboat Mountain across the sand dunes to North Table Mountain. The longest mule Deer migration in North America follows the Continental Divide in this location. See below for more information on the migration.

"Arising from the southern Red Desert like a mirage, the Killpecker Sand Dunes are the largest living dune field in North America, stretching over 109,000 acres from the Green River Basin 55 miles east to the Great Divide Basin.

Ground from the granite of the Wind River Mountains by glaciers, the sand accumulated on the banks of the Big Sandy and Little Sandy Rivers downstream was blown across the continental divide by westerly winds over thousands of years. Each winter, the sand collects snow melt and windblown ice deposits, which support the vegetation that stabilizes the dunes. The collected water creates ephemeral oases in the desert that sustain a surprising array of wildlife, from migratory shorebirds to salamanders and freshwater shrimp. The dunes are also a haven for mule deer and a rare desert elk herd. Travelers may hear the sand 'sing' as sand avalanching over the crescent-shaped dunes creates a roaring, booming sound that can last for several minutes." (Citizens for the Red Desert, reddesert.org)

"The longest big game migration corridor in the lower 48 United States begins just north of Rock Springs in the Red Desert.

Twice a year, mule deer migrate between their winter range in the Red Desert sagebrush and their high elevation summer range 150 miles north in the Hoback. This one-way trip, aptly called the Red Desert to Hoback migration, allows the deer to access highly nutritious forage, essential to their health and survival, over the course of several months as the sage and grasses green up throughout the spring. Mule deer are extremely faithful to their migration routes, with herds traveling the exact same paths year after year. Recent scientific research suggests migration routes are passed down from one generation of deer to the next, in a continuous line spanning centuries." (Citizens for the Red Desert, reddesert.org)

The photo below was taken looking southeast. The western edge of the Continental Divide Basin runs from the ridge of Steamboat Mountain (right margin of the picture and behind) to the far side of the Leucite Hills (horizon on the right side of the photo) before turning east to run beyond Spring Butte and Black Rock. The elevation of the Continental Divide at Steamboat Mountain is approximately 8700 ft.

This area of Wyoming is known as 'The Red Desert'. It extends from the southern end of the Wind River Range in the north to below the Colorado border in the south. It's a little wider than the Great Divide Basin east to west covering about 15 to 20% of the State. The wild and unpopulated nature of this are may help explain why Wyoming is the least populated State in the United States with just over a half million people.

“The Great Divide Basin is the only place in North America where the Continental Divide splits into two paths creating a basin in the middle where precipitation flows neither to the Atlantic or Pacific Oceans. The Alkali Draw and Pinnacles Study Areas are visible from this spot. Alkali Draw contains rugged cliff escarpments and its springs and seeps help support several wildlife herds. The pinnacles are named for their pyramid shapes and colorful landforms. The country is some of the wildest undeveloped desert lands in the northern Rocky Mountain states.” (Citizens for the Red Desert, RedDesert.org)

The photo below is of the Tri-Territory Monument. This spot is at the intersection of the Continental Divide and the 42nd parallel. The 42nd parallel is the southern border of Oregon and Idaho and the northern border of California, Nevada, and Utah. The elevation here at the Continental Divide is 7775 feet above sea level.

“The Tri-Territory Site: Outpost of Invisible Empires

The history of America’s massive territorial expansion from the beginning of the 19th century is a complex story of treaties, purchases, annexations, compromises and conquest. At various times, Great Britain, France, Spain, Mexico and the one-time Republic of Texas all laid claim to vast territories ranging from the Mississippi River west to the Pacific—without, of course, any regard for the ownership rights of the native peoples who were already there.

On a remote sagebrush flat in Sweetwater County, Wyo., a few miles northeast of Steamboat Mountain, a simple, seldom-visited monument commemorates a place that, on maps, was once very important—though until the 1960s it was invisible. The monument marks the site on the 42nd parallel of north latitude where the boundaries of the three dominions that would make up the bulk of the American West outside of Texas all met—the Louisiana Purchase, the Oregon Territory and Mexico: the Tri-Territory Historic Site.

The Louisiana Purchase

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson’s diplomats negotiated the Louisiana Purchase with France. At a single stroke, the acquisition of 828,000 square miles at a price of $15 million nearly doubled the size of the United States. The Purchase’s eastern boundary was the Mississippi; in the West, the Continental Divide. The states carved out within its borders would come to be Missouri, Arkansas, Iowa, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska and Oklahoma in their entirety, plus most of the land in Louisiana, Colorado, Montana, Minnesota, Montana, Kansas and Wyoming.

To explore the Purchase, seek the theoretical Northwest Passage, establish an American presence in the Oregon Country, conduct scientific and economic studies and establish trade with Native American tribes, Jefferson commissioned Lewis and Clark’s epic Louisiana Purchase Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, in 1804.

For more than two years, from May 14, 1804, to Sept. 23, 1806, Capt. Meriwether Lewis, who was Jefferson’s secretary, and Lt. William Clark, the expedition’s co-commanders, led a party of five non-commissioned Army officers, 30 soldiers, and a small assortment of civilians, including the legendary Lemhi Shoshone woman Sacagawea. Theirs was a two-way, 8,000-mile journey by keel boat, canoe, on horseback and on foot from present-day eastern Missouri through what are now Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, Montana, Idaho and Oregon to the Pacific Ocean and back, with the loss of only one member of the expedition and two Blackfeet warriors.

The Oregon Country

The “Convention of Commerce between His Majesty and the United States of America,” signed in London on Oct. 20, 1818, set the boundary between the United States and British North America –what’s now western Canada—as the line of the 49th parallel of north latitude from “Lake of the Woods [in present-day northern Minnesota] to the Stony Mountains [the Rocky Mountains].” West of those mountains was the region known to Americans as the Oregon Country, while the British called it the Columbia Department. On paper, the two nations agreed on joint control over the area, but in fact the Hudson’s Bay Company, the powerful Anglo-Canadian fur trading enterprise, took serious measures to expand its business there and keep American fur traders out.

By the mid-1840s, however, the tide of American emigration to the Oregon Country along the Oregon Trail, encouraged by expansionists in Congress and elsewhere, brought steadily rising pressure on the U.S. government to remedy the situation. The result was a series of negotiations with the British, leading to the Oregon Treaty of 1846.

The treaty ended the joint occupation of the Oregon Country, setting the boundary between the United States and British North America as the 49th parallel all the way west to the Pacific, with the exception of Vancouver Island, which remained British. Those living south of the 49th parallel were declared American citizens, and those north of the line became British. Two years later, in 1848, Congress organized the American half of the region as Oregon Territory, and formed Washington Territory from it in 1853.

The southern boundary of the Oregon Country/Oregon Territory was the 42nd parallel of north latitude running from the Rockies to the Pacific; the region south of that line was Mexican territory.

Mexico and the Mexican Cession

James K. Polk of Tennessee, who served as the 11th president of the United States from 1845 to 1849, was an ardent expansionist. He was committed to Manifest Destiny, the widespread cultural belief that America was destined to expand its dominion completely across the continent to the Pacific. It was Polk who advocated the annexation of the Republic of Texas and signed the legislation making it a state in 1845, and also led the negotiations with Britain that resulted in the Oregon Treaty of 1846 and American absorption of the Oregon Country.

The Texas-Mexico border had long been the subject of a bitter dispute. In September of 1845, Polk sent John Slidell, a prominent lawyer, to Mexico City to negotiate an agreement that would settle the Rio Grande as the international boundary. Slidell also carried with him Polk’s offer to purchase California and the province of New Mexico, (which would come to encompass New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and swatches of three additional states), for a sum of up to $30 million.

When the Mexican president, José Joaquín de Herrera, refused to see Slidell, Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to occupy the disputed region between the Nueces and Rio Grande rivers and began preparing a war message to Congress. Before he could deliver it, however, he learned that Mexican cavalry had crossed the Rio Grande and attacked a small detachment of Taylor’s troops, killing 11 and capturing 52. In a quickly revised war message delivered to Congress, Polk declared that Mexico had “invaded our territory and shed American blood on American soil.” War was officially declared on May 11, 1846.

The conflict—highly controversial in the United States—ended two years later with an American victory on Feb. 2, 1848, when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed. The Rio Grande was affirmed as the southern boundary for Texas, and, for $15 million, the United States took possession of what are now California, Utah, Nevada, nearly all of Arizona, a large portion of New Mexico and significant sections of Wyoming and Colorado. This latest acquisition of some 529,000 square miles became known as the Mexican Cession.

Thus it was that by 1848, the overwhelming bulk of what would come to be known as the West was in American hands.

The Tri-Territory Historic Site

In the 1960s, the Kiwanis Clubs of Rock Springs, Lander, Riverton and Rawlins, Wyo. worked with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management to create a monument in Sweetwater County at the point where the Louisiana Purchase, Oregon Country and Mexican Cession met, at the intersection of the 42nd parallel of north latitude and the Continental Divide. The coordinates are 42 degrees north latitude, 108 degrees, 55 minutes, 1.7 seconds west longitude.

Dedicated on Sept. 24, 1967, the heart of the site is a bronze plaque mounted on a masonry monument and three flagpoles to represent Britain, Mexico and France, with a fourth atop the monument itself for the United States.

Ironically, the plaque itself later presented a problem when the site was proposed for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Writing for The American Surveyor in June 2015, Henry J. Kessner, P.E., P.S., described the situation:

There was an attempt by the Kiwanis Clubs and the BLM to include the Tri-Territory Site in the National Register of Historic Places. BLM officers vigorously pursued the proposal through the Wyoming Recreation Commission. The Commission cited two weaknesses in the BLM proposal, one of which could be corrected and another ‘which can be in no way avoided.’ The first weakness to the proposal, that which could be corrected, was the wording on the plaque which read, in part ‘...Louisiana Purchase (1803) The Northwest Territory (1846) and Mexico (1848)’. The reviewing historian, Ned Frost, correctly pointed out that ‘The Northwest Territory’ is an incorrect reference to that region of the Tri-Territory acquisitions. In all histories of the United States, ‘The Northwest Territory’ was the area that was to become the States of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and a part of Minnesota. The correct designation should be, ‘Oregon Country’. The second weakness to the proposal was that the site ‘is not in itself a place at which any historic event occurred.’ Because of these ‘weaknesses’ and other bureaucratic obstacles the nomination was vetoed. No attempt to change the wording on the plaque or to militate the other deficiencies in the nomination has to date been attempted.

No battles were fought at the Tri-Territory Site. It is miles from any emigrant trails and even farther from the railroad. It was never a settlement, nor was it a military post or a Native American encampment. Yet, for all that, its importance—and its legacy—are beyond question. It was, and will always remain, the hinge and lynchpin of the American West.

The site lies in Wyoming’s Red Desert, 28 air miles southeast of Farson and 32 air miles northeast of Rock Springs. To reach it requires more than 45 miles of travel from Rock Springs, only 10 miles of which is on a paved highway, U.S. Highway 191. The rest is on dirt roads, and a wintertime visit is not recommended.” (wyohistory.org)

"The Jack Morrow Hills, named for a 19th century crook and homesteader, run north to south between the Oregon Buttes and Steamboat Mountain and define the western edge of the Great Divide Basin. These hills are a complex of sagebrush clad ridges and rims, with seeps and drainages that provide important habitats for birds and ungulates including sage grouse, pronghorn, elk, and mule deer. The east facing slopes of Bush Rim sport a kaleidoscope of colorful sediment layers and hidden springs supporting lush groves."(Citizens of the Red Desert, RedDesert.org)

This is a picture of Continental Peak. The Honeycomb Buttes are just below. The Continental Divide passes over the top of Continental Peak and this peak along with The Oregon Buttes marks the northern end of the Great Continental Divide Basin.

This photo of the Oregon Buttes was taken a couple miles south of the Oregon Trail and is a sight that the approximately half million people who emigrated west on the Oregon Trail in the mid 1800's would have seen. Except for the addition of a few roads through this area, not much has changed since that time.

In person the Buttes seem a lot larger and can be seen for a considerable distance. The Continental Divide passes over the Oregon Buttes and marks the northern end of the Great Continental Divide Basin. The Oregon Trail passed over the Continental Divide northwest of the Buttes.

“The Oregon Buttes were a major landmark for travelers on the Oregon Trail. The name is significant because the Buttes were roughly the beginning of the Oregon Territory and also helped the emigrants be encouraged, even though there were hundreds of miles of tough going ahead. About 12 miles to the southwest of the Oregon Buttes is the location where the Oregon Territory, Mexican Territory, and Louisiana Purchase had a common boundary.” (U.S. Department of the Interior – Bureau of Land Management)

The two track road near the left margin of the photo below is the actual Oregon Trail that many thousands of people passed over in covered wagons or pushing hand carts on their way west in the mid 1800's. The butte on the left margin is Pacific Butte. A nearby Bureau of Land Management marker says this about Pacific Butte, "The great height and mass of the Butte combined with a ridge to the north paralleling the Oregon Trail created a visual channel through which travelers migrated on their way to South Pass.” (U.S. Department of the Interior – Bureau of Land Management)

That visual channel is evident as it leads to the horizon where it crosses the Continental Divide at South Pass.

The mountains on the horizon on the right side of the picture are the Wind River Range.

The photo below shows where the Oregon Trail passed over the Continental Divide. The name of this spot is South Pass. The two track road is the actual Oregon Trail. The Bureau of Land Management fenced in about 10 acres here because of the historical significance of this place. The two monuments in the foreground have been here more than 100 years. I had a copy of the USGS map loaded on my phone and, zoomed in all the way, it appears that the contour line for the Continental Divide passes between the monuments. It was pleasing to see that neither monument has been shot or vandalized in any way. It probably helps that this place is somewhat remote and a little hard to get to. Even though it seems very nondescript, standing on the Oregon Trail looking at the monuments I felt an eerie feeling of the flow of history thinking about the half million people that passed this spot in covered wagons 170 years ago, what motivated them to cross 2000 miles of wilderness, and the hardships they endured doing it. Perhaps I'm not the only one who felt that and possibly that's part of the reason why the monuments have been respected.

The photo was taken looking eastward after the storm in the previous photo had passed. I'll have more information about this place and the monuments in subsequent photos.

“Even after the rediscovery of South Pass in 1824, it was years before the route was used extensively. Fur trapper/trader William Sublette brought a small caravan of wagons to South Pass in 1828. While his party did not take wagons over the pass, they demonstrated the feasibility of using them. Captain Benjamin Bonneville took the first wagons over South Pass in 1832. But it was U.S. Government explorer, Lt. John Charles Fremont, who was responsible for publicizing the South Pass route. Scattered references to an easy passage over the Rockies had appeared in newspapers for a decade, but in 1842 Fremont created enthusiasm for South Pass by explaining that a traveler could go through it without any “toilsome ascents”. As knowledge of South Pass became widespread, a great western migration commenced. Thousands of Mormons, and future Oregonians and Californians, would cut a wide swath along the route in the next twenty years.” (U.S. Department of the Interior – Bureau of Land Management)

This photo was taken a while after the previous photo and is looking west. Again, the two track road is the actual Oregon Trail, the route of the western expansion of the U.S. in the mid 1800's.

“Even after the rediscovery of South Pass in 1824, it was years before the route was used extensively. Fur trapper/trader William Sublette brought a small caravan of wagons to South Pass in 1928. While his party did not take wagons over the pass, they demonstrated the feasibility of using them. Captain Benjamin Bonneville took the first wagons over South Pass in 1832. But it was U.S. Government explorer, Lt. John Charles Fremont, who was responsible for publicizing the South Pass route. Scattered references to an easy passage over the Rockies had appeared in newspapers for a decade, but in 1842 Fremont created enthusiasm for South Pass by explaining that a traveler could go through it without any “toilsome ascents”. As knowledge of South Pass became widespread, a great western migration commenced. Thousands of Mormons, and future Oregonians and Californians, would cut a wide swath along the route in the next twenty years.” (U.S. Department of the Interior – Bureau of Land Management)

The photo below is a composite. The foreground photo was taken looking ENE and is my first attempt using 'Low Level Lighting'. I had an LED panel with me and set it up about 30 yards behind me to the right. I set it at 1% of it's available brightness. It still seemed bright in the darkness. The Milky Way photo was taken looking south. The northern 1/3 of the sky was overcast but I was still able to see Polaris so I set up my star tracker and used that for the sky photo. The light pollution on the horizon on the left is from Rock Springs which was about 50 miles away by line of sight. The light pollution on the right is from Farson which was about 30 miles away.

“Without South Pass, the entire history of the United States’ expansion west of the Mississippi would have been different. South Pass got its name to distinguish it from the tedious and difficult northern route through the Rocky Mountains taken in 1805 and 1806 by Lewis and Clark through the Bitterroot Mountains.

As any aficionado of the Corps of Discovery knows, the Bitterroots nearly destroyed the dreams of that expedition. By the time the Corps stumbled out of the mountains, they were frozen and near death from starvation. Even today, few roads cross the Bitterroots, and the country between the great Missouri River and the mighty Columbia remains as topographically complicated as it was when Lewis and Clark crossed it.

Thus, the discovery of a direct land route across the Continental Divide with a relatively easy grade was a godsend to those who hoped to see the United States of America stretch from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Without South Pass, it is almost certain that the Pacific Northwest would have been permanently claimed by the British and the southern part of the continent would have remained part of Mexico. South Pass, the isolated little saddle that straddles the Continental Divide in the midst of Wyoming, still the least populated state in the nation, truly provided the key to today's United States.

While the pass had been used by American Indians for millennia, the first known usage by white men occurred in 1812 when Robert Stuart and six companions crossed the mountains on their return to the East from Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia, on the Oregon coast. In 1832, Capt. Benjamin Bonneville and a caravan of 110 men and 20 wagons became the first group to take wagons over the pass.

Then, on July 3, 1836, missionary Marcus Whitman crossed the pass with his wife, Narcissa, and their missionary companions, Henry Spalding and Eliza Hart Spalding. Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Hart Spalding became the first white women to cross the Continental Divide at South Pass.

This tiny trickle of white people would become a stream in the 1840s and a river in the 1850s and 1860s. Between 1841, when the first Oregon-bound wagon train was organized, and 1869 when the transcontinental railroad was completed, somewhere between 350,000 and 500,000 emigrants crossed South Pass on the trails bound for Oregon, California or Utah’s valley of the Great Salt Lake. Their multiple routes converged to form a common trail corridor near Fort Kearny in what’s now central Nebraska before parting again beyond Dry Sandy, a short way west of South Pass.

As the years went by, commercial freight traffic, bound east as well as west, became steadily more common on the route across South Pass. The 1850s saw stagecoaches carrying passengers and mail offering first monthly, then weekly and finally daily service.

The Pony Express was established in the spring of 1860, and at its inception could carry a letter from St. Joseph, Missouri via South Pass to Sacramento, California in just two weeks. Construction of a transcontinental telegraph line began about the same time along the same route; by the fall of 1861 the line was finished and the Pony Express disbanded.

After 1862, much of the commercial traffic moved south to the Overland Trail, which crossed what’s now southern Wyoming by a more direct route, most of which later became the route of the Union Pacific Railroad and Interstate 80. The telegraph continued to follow the South Pass route until the late 1860s, when it was moved south to the railroad line.

For westbound travelers, the push to the South Pass crossing started at Independence Rock, where their slow, steady climb over the Continental Divide began. Many didn't even realize the backbone of the Rockies had been conquered until they reached Pacific Springs west of the pass, so gradual was the incline.

And the exact elevation of that backbone has been disputed throughout modern times. Today, it is fairly well established that the crest of South Pass is situated on the Continental Divide in Fremont County, Wyo., about 10 miles southwest of South Pass City, at 42 degrees 21 minutes north latitude and 108 degrees 53 minutes west longitude, at an elevation of 7,440 feet above sea level, or 2,267.712 meters.

Until recently, however, there was a surprising amount of confusion about the elevation. The noted historian, Dale L. Morgan, gave its elevation as 7,550 feet above sea level, a figure that has often been cited though it actually reflects the elevation of the Continental Divide to the north of the pass. The U.S. Geological Survey’s Pacific Springs 7.5 minute quadrangle gives the elevation as 7,412 feet, as do many other reference works.

During a June 2006 field survey, Colleen Sievers of the U.S. Bureau of Land Management’s Rock Springs office took a Global Positioning System reading at the Meeker and Whitman monuments, normally considered to be "the summit," that produced a reading of 7,440 feet above average mean sea level, with an error factor of plus or minus three feet.