- Joined

- May 5, 2012

- Messages

- 1,727

Preface

The Uinta Mountains have a habit of swallowing people.

Mount Watson under shadow of clouds at Hope Lake on the Notch Mountain Trail. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Working as a journalist in Utah, I've reported on many search and rescue operations in the range. I was there as volunteers scoured the area near Haystack Lake for little Benjamin Myrup in 2007.

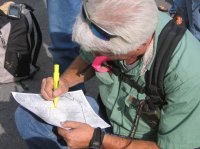

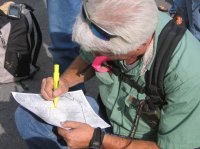

A searcher marks a map during the effort to find Benjamin Myrup on Tuesday, Sept. 11, 2007. He disappeared near Washington Lake while camping with family. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

In 2005, I watched swift-water teams sweep the East Fork of the Bear River as it was swollen with snowmelt, probing for the body of Brennan Hawkins.

Rescuers attempt to locate a body trapped by debris in the East Fork of the Bear River on Monday, June 20, 2005. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Hawkins, it turned out, had hidden from rescuers for fear of being abducted. He made it home safely.

Steven Wiscombe once described to me how he became separated from his grandson after reaching the summit of Kings Peak. He hid under a rock as crackling bolts of electricity peppered the naked peak.

With the help of strangers in Anderson Basin, he was reunited with his relieved family after a cold and worrisome night apart.

Those are the success stories.

The strained face of Kevin Bardsley tells the other side. His son Garrett vanished in the Cuberant Basin in 2004 and has never been found. Kevin devoted himself to helping rescue other lost children for years afterward.

Kevin Bardsley hugs a searcher at the Crystal Lake Trailhead after learning Benjamin Myrup was located on Tuesday, Sept. 11, 2007. His volunteer organization, the Garrett Bardsley Foundation, assisted many search and rescue operations. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The body of Eric Robinson of Melbourne, Australia, still remains somewhere in the range. He'd set off to hike the Highline Trail in 2011 but never made it to the terminus. Efforts to find him were fruitless.

(Author's note: Robinson's remains were located and recovered in Aug. 2016, after the publication of this piece. More on that in my article for KSL.)

There were others.

Of all the stories over the years though, of all the mystery and anguish, no disappearance has stuck with me more than that of Kim Beverly and Carole Wetherton.

Kim Beverly's driver license photo, as displayed by the Summit County Sheriff's Office in Sept. 2003.

Carole Wetherton's driver license photo, as displayed by the Summit County Sheriff's Office in Sept. 2003.

Searchers found their remains at a crude campsite near the Middle Fork of the Weber River, nine months after they'd embarked on a simple day hike. Their recovery brought an end to untold frustration and uncertainty. It gave finality to Kim and Carole's family.

Unfortunately, the find also gave rise to a mystery. For more than a decade since their deaths, their story has remained incomplete. Kim and Carole were not where anyone had expected them to be. The questions of how they ended up where they did and why have never received satisfactory answers.

What follows is an attempt to thoroughly review the evidence, developing new conclusions along the way about what went wrong. Understanding the truth of Kim and Carole's experience can provide invaluable lessons about survival and how simple choices can mean the difference between life and death when in the backcountry.

Some of these findings directly contradict those offered by law enforcement. However, this should not be read as an indictment of the many searchers, both professional and volunteer, who devoted thousands of hours to find Kim and Carole. Their work was exhaustive and did eventually result in a successful recovery. Without their dedication, Kim and Carole might have remained undiscovered even to this day.

As have Garrett and Eric.

The Facts

Gloomy gray skies and chill autumn air greeted Kim and her mother Carole when they started out hiking on Monday Sept. 8th, 2003. The pair had come to Utah from their respective homes in Georgia and Florida for a vacation, basing out of a rental in Park City.

Lily Lakes, looking east. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The first hint of trouble didn't arrive until Kim and Carole missed their return flights home on Saturday, Sept. 13. Family and friends notified Park City police who, in turn, asked law enforcement agencies all across northern Utah to check area trailheads for the gold Jeep Cherokee Kim and Carole had rented.

The following day, Summit County Sheriff's Deputy Jim Snyder spotted the Jeep at the Crystal Lake Trailhead. A sheriff's sergeant soon located a guide book in the vehicle. It showed a circle around an entry for Clyde Lake. Likewise, the police found evidence in the condo showing the women were interested in the Clyde Lake loop, a popular path linking two established trails in the vicinity of Wall Lake.

By that point, almost a full week had passed since the two women had last been seen. Kim and Carole, as it would turn out, were already dead.

No one knew that for certain then. The authorities launched an immediate, intensive search. Bloodhounds sniffed around the Jeep and then bolted toward Wall Lake.

Wall Lake, Mount Watson and The Notch as they appear from the Notch Mountain Trail. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

So-called "hasty teams" sped out along all of the area trails, even up and over the Notch to Meadow Lake as well as down the Middle Fork Weber River Trail to Holiday Park.

For 10 straight days, they scoured the rugged region. They had no luck. That initial frenzy of activity started to fade. Other matters proved pressing and the sheriff's office scaled back the search. Still, even after the reality set in that Kim and Carole were beyond help, rescuers continued spending weekends in the Uintas, hoping to bring the women home.

That didn't happen until the following June — nine months after that first worried call to police — when rescue dog trainers working with deputies spotted a bit of reflective space blanket material flashing in the sun. It led them to a makeshift rock shelter.

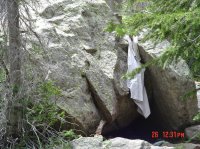

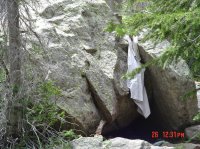

The location of Kim Beverly and Carole Wetherton's rock shelter in the Uinta Mountains. Searchers located their remains here in June, 2004. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

It sat, oddly enough, just a short distance from the lightly-used trail in the Middle Fork, the same one the hasty team had gone down on the very first day. In fact, searchers had walked within a few hundred feet of the shelter rock several times without ever knowing it was there.

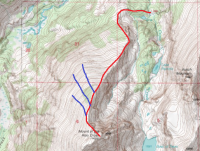

Because of the site's close proximity to the trail, investigators posited Kim and Carole had actually arrived there from another direction — from the south.

Deputies came to believe the two women made an unwitting error in judgement. They decided Kim and Carole had accidentally turned onto the Middle Fork Weber River Trail at a junction just to the west of Long Lake. If that were true, it would have led them up and over the saddle between Long Mountain and Mount Watson.

That theory, reported on and repeated by local media, became the accepted narrative. No one seemed to question why the bloodhounds had not gone east to Long Lake, but instead north toward Wall Lake and The Notch.

The Notch, as it appears from the southern end of Wall Lake. The prominent feature has long been a popular destination for hikers. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Officials did not point out the evidentiary discrepancies that showed Kim and Carole had intended to hike the Clyde Lake loop in the interviews they gave.

Seeds of doubt started to germinate when, on the third anniversary of their disappearance in 2006, KSL published scans of photographs Kim and Carole had taken on a small film camera. The exclusive story from reporter Marc Giauque ignited discussion online among hunters, hikers and geocachers who recognized familiar landmarks in the images.

The pictures, which have almost all now been plotted with relatively precise GPS coordinates, disprove the notion Kim and Carole went to Long Lake.

They went instead, as the evidence first suggested, to Wall Lake and beyond.

Unfinished maintenance work on an unofficial trail near Clyde Lake on Sunday, Oct. 4, 2015. Kim and Carole would have crossed here after leaving the Notch Mountain Trail. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

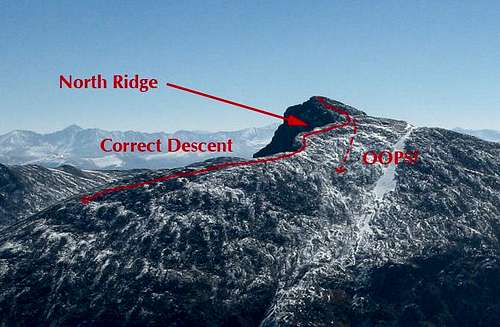

They completed half of the Clyde Lake loop before, for an unknown reason, diverting off their planned route. They turned west, going off-trail to Hidden Lake before heading south to end up at the rock where they lost their lives.

No one will ever know why they left the trail. They took that secret to the grave. The totality of the facts, though, make the argument Kim and Carole might have died making an intentional attempt to reach safety by circling Mount Watson.

A view of Mount Watson from the Notch Mountain Trail. The cone-shaped peak would have been visible to Kim and Carole from the very beginning of their hike. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

If this theory is correct, they made a brave effort to extract themselves from a dangerous situation. They may very well have exhibited impressive resilience after making a few incremental mistakes that carried severe and unexpected consequences.

My Interest

I had just started out as a cub reporter at the time of Kim and Carole's disappearance. A radio station in Salt Lake City had brought me on staff following an internship the prior spring. In fact, I was still slaving away on my final semester as an undergrad studying journalism at the University of Utah when the initial events unfolded in September of 2003.

The newsroom consisted of a small group of anchors, none of whom did any field reporting. My job was to extend their coverage by going out in the field. However, the Uinta Mountains were then beyond my range, as I lacked the equipment to establish a reliable live signal there.

As such, when the story of the search for Kim and Carole broke, I was relegated to covering it from the newsroom. Over the course of the weeks and months, I received updates from the Summit County PIO (press information officer) and then-Sheriff Dave Edmunds.

While I wasn't up there in person, the situation struck a chord.

As a teen I'd backpacked Henrys Fork and East Shingle Creek.

A Boy Scout troop at East Shingle Creek Lake in Sept., 1995. The author stood second from the right. (Photo: unknown)

I'd stayed at Camp Steiner, a facility operated by the Boy Scouts of America that sits about 5 miles away from the search area. I'd rappelled and caught salamanders there. I'd huddled in terror one night as a dry electrical storm lashed the high country with lightning. The animalistic fear inspired by simultaneously seeing the white-blue flash and feeling the gut-rumbling thunder roar remains palpable.

I had also spent significant time on the East Fork of the Bear River BSA reservation a bit farther north.

Sign welcoming visitors to the East Fork of the Bear River Scout Reservation in June, 1996. The camp has since been renamed the Hinckley Scout Ranch. (Photo: Cherie Cawley)

For several successive summers, I took part in leadership training courses at the East Fork reservation, both as a participant and as a staff member. During one such June outing, while serving as Senior Patrol Leader responsible for a group of nearly 100 youth, we'd endured a surprise blast of late June snow. In an organized panic, my staff evacuated the boys through the dark as lodgepole pines groaned, tipped and crushed the scouts' little dome tents.

All this is to say, as a young man I considered the western Uintas my home range — they were familiar turf.

It stunned me at the time how Kim and Carole had managed to disappear so completely, in an area that sees so much traffic.

Then, in 2007, I stumbled across a summitpost.org page about the Beverly/Wetherton case. Contributors noted the Summit County Sheriff's Office had never provided the exact location of Kim and Carole's encampment, only saying it had sat somewhere along the Middle Fork of the Weber.

The page's creator provided photographic proof that the Summit County Sheriff's Office had the route all wrong. He questioned an assertion from Carole Wetherton's husband that a GPS unit could have helped save her life.

My curiosity was aroused. I resolved to find Kim and Carole's shelter and learn, as best I could, what had really happened to them.

The author standing on the shore of Watson Lake at sunrise on Saturday, Aug. 27, 2011. Photo was taken on a failed attempt to locate Kim and Carole's shelter. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The Terrain

In order to understand what happened to Kim and Carole, one must first become familiar with the area in which they vanished.

The view west into the Middle Fork of the Weber River gorge from near the Three Divide Lakes on Saturday, Oct. 17, 2015. Hidden Lake was obscured from Kim and Carole's view by the pines. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The western end of the Uinta Mountains is the range's most accessible.

Much of the land is public, falling within the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest. The congressionally-designated High Uintas Wilderness Area sits a bit to the east, encompassing popular backpacking destinations such as the Naturalist and Grandaddy Basins.

Visitors are able to reach these and many other scenic spots via the Mirror Lake Highway.

The Mirror Lake Highway in autumn. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The two-lane state road, also designated S.R. 150, connects the town of Kamas, Utah, to Evanston, Wyoming. It is paved for its length and crosses Bald Mountain Pass, its highest point at roughly 10,700 feet above sea level.

Getting to Bald Mountain Pass from Salt Lake City requires just an hour-and-a-half drive. So in spite of their wild character and at times confusing topography, the areas along the highway see heavy use.

They're spotted with small lakes, which the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources stocks with fish. Between the lakes are marshes flush with grass and wildflowers. Surrounding all are forests of spruce and pine that give way to barren, rocky peaks.

The Utah Department of Transportation closes gates on the highway to prevent wheeled-vehicle access during a period from roughly November to June each year (with certain variation for weather conditions).

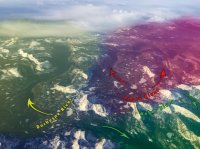

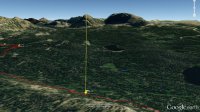

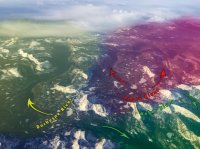

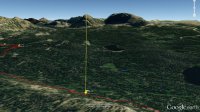

Aerial view of the Mirror Lake region of the Uinta Mountains, looking south. Kim and Carole went missing in the area at the right of the frame. (Photo: Mark Cawley)

During this time, snow covers the road, which is groomed for use by snowmobiles.

A Utah Department of Transportation road closure sign blocks the Mirror Lake Highway on Saturday, May 16, 2015. Melting snow allowed UDOT to open the road in June that year. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Winter snowfall in the western Uintas gives rise to several of Utah's most significant waterways. The Weber, Duchesne, Provo and Bear Rivers all have headwaters within a few miles of one another.

The Provo River enters into Trial Lake on Saturday, May 16, 2015. High Uinta lakes often hold ice well into June. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

In fact, the Mirror Lake Highway passes along or even between these headwaters as it crosses the range from north to south.

A graphical view of the major river drainage systems in the western Uinta Mountains. The Bear River sat out of view beyond the bottom of the frame. (Photo: Mark Cawley)

This is true even at the lake that gave the highway its name — Mirror Lake. It empties eastward into the Duchesne River. Just across the pavement to the west, Reids Meadow helps feed the headwaters of the Weber.

The Crystal Lake Trailhead sits in the upper reaches of the Provo River drainage. It's about 4 highway miles southwest of Bald Mountain Pass. Visitors reach it on a spur road that also provides access to popular U.S. Forest Service campgrounds at Washington and Trial Lakes.

The turnoff from the Mirror Lake Highway leading to Trial Lake, Wall Lake and beyond. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The trailhead serves as the access point for multiple trails.

A sign at the Crystal Lake Trailhead marks the start of the Notch Mountain Trail. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

They include well-traveled routes like the Notch Mountain and Lakes Country Trails (the latter identified as the Smith Morehouse Trail on some maps).

A sign at the beginning of the Lakes Country Trail. The Lakes Country and Notch Mountain Trails begin within 100 feet of one another. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

This was the area into which Kim and Carole ventured.

Some of the terrain reachable from the Crystal Lake Trailhead (which, again, rests within the Provo River drainage), actually falls within the Weber River drainage.

At the Three Divide Lakes, waters shed two directions, ending up in two different rivers. Both eventually flow through the Wasatch Mountains, but one heads to Ogden and the other to Provo.

The view from Three Divide Lakes looking northeast to The Notch on Saturday, Oct. 17, 2015. From this location, water flows downhill in different directions into two separate river systems. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Mistakenly following the wrong stream in this area can have significant consequences. Ogden and Provo are 70 miles apart.

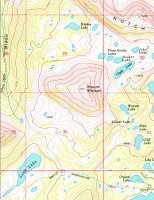

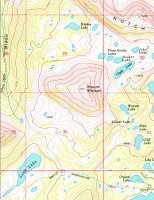

The U.S. Geological Survey's 7.5-minute Mirror Lake Quadrangle topographic map describes the locality well.

(Image courtesy U.S. Geological Survey)

It also encompasses the entirety of the search area covered by the Summit County Sheriff's Office after Kim and Carole's disappearance.

The Maps

Even today, keeping all of these lakes and trails straight can prove a challenge. That would have been especially true for Kim and Carole, who were not familiar with the area.

The view south from The Notch, looking down on North Twin Lake, South Twin Lake and Wall Lake. Kim and Carole did not make it quite to this point, instead circling around the near shore of North Twin. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

They had done at least some research. As stated above, the Summit County Sheriff's Office described finding a guidebook in their rental Jeep. Kim and Carole had circled Wall and Clyde Lakes. Park City police also located "documentation" in their room with a check mark next to Clyde Lake.

The autumn afternoon sun illuminates the southeastern shore of Clyde Lake. Kim and Carole could have followed this trail back to the trailhead. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The theory that Kim and Carole died while attempting an intentional orbit of Mount Watson hinges on the idea that they knew the Middle Fork Weber River Trail existed. They would have need to see it on maps while planning their hike, or while they were in the actual area.

Not all maps, however, show that trail.

As of 2015, it is inventoried on U.S. Forest Service recreation maps.

USFS recreation map showing the Middle Fork Weber River Trail as of Sunday, Aug. 16, 2015. (Image courtesy U.S. Forest Service)

It has also appeared on the USGS Mirror Lake Quadrangle topographic map.

The vicinity of Mount Watson on the 1991 revision of the U.S. Geological Survey's Mirror Lake Quadrangle topographic map. Note the presence of the Middle Fork Weber River Trail as well as the absence of the Clyde Lake Trail. (Image courtesy U.S. Geological Survey)

There are multiple versions of this map, though. The 1998 revision would have been the most recent available at the time of Kim and Carole's hike. It does not include the Middle Fork Weber River Trail segment between Long Lake and the turnoff for Abes Lake.

The vicinity of Mount Watson on the 1998 revision of the U.S. Geological Survey's Mirror Lake Quadrangle topographic map. The Middle Fork Weber River Trail was removed without explanation. (Image courtesy U.S. Geological Survey)

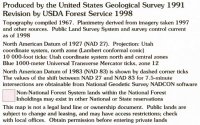

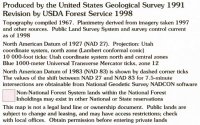

That revision (since replaced) includes a note which attributes the changes to the U.S. Forest Service.

(Image courtesy U.S. Geological Survey)

In order to understand why the trail was removed, I reached out to the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest.

The response came in an email from Brenda Bushell with the Heber-Kamas Ranger District. She, as coincidence would have it, was the last person known to have seen Kim and Carole alive. She encountered them at the trailhead on the day of their hike.

"I don't understand why our trails don't match up with the Quads," Bushell said. "Multiple of our trails don't show up on them."

Not satisfied, I next submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to the U.S. Department of the Interior (parent agency of the U.S. Geological Survey), seeking information about the trail's omission.

This is verbatim what I requested:

The response was thus:

So, in effect, no one can say now why the trail segment was omitted from the 1998 map.

It does say something about the trail, however. At some point, someone deemed it unworthy of inclusion.

Unlike the well-maintained trails that fan out from the Crystal Lake Trailhead, the Middle Fork Weber River Trail is indistinct.

A small cairn marks the Middle Fork Weber River Trail. The trail marker remained almost entirely hidden behind the undergrowth on Saturday, July 18, 2015. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

When walking along it, one often has to watch for cairns, plastic ribbons fixed to tree limbs or spray paint on rocks in order to follow the path.

A piece of blue plastic ribbon attached to a tree along the Middle Fork Weber River Trail. This kind of marker often fades with time and has to be replaced. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

A hiker could cross the route on a perpendicular axis and not realize he or she had intersected an official trail.

Red spray paint marks the otherwise faint Middle Fork Weber River Trail. Bright colors like this tend to stand out against the natural hues of the landscape. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

As casual hikers, Kim and Carole were most likely not using full quadrangle topographic maps. It's more likely they relied on books. If those showed a trail in the Middle Fork, they might have reasonably expected it to look similar to the trails they'd already used — broad and obvious.

A rain-soaked segment of the Notch Mountain Trail. The well-beaten footpath doesn't present hikers with the same navigational challenges as the Middle Fork Weber River Trail. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Using maps from guidebooks would have put Kim and Carole at a disadvantage. Those maps would likely have lacked the sort of information necessary to make informed decisions about off-trail travel, such as elevation contours or tree-cover shading.

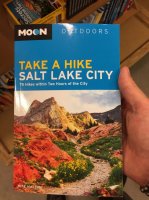

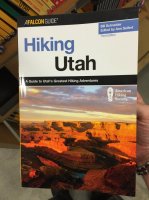

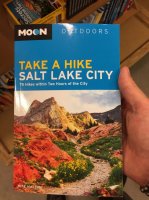

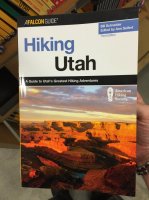

To illustrate this point, I attempted to do as a visitor to Utah might by stopping in at the Salt Lake City REI store. There, I sampled the available literature on the retailer's shelves.

Two of the books I checked included descriptions of trails in the Crystal Lake vicinity.

An example of the trail guides available at the Salt Lake City REI store on Wednesday, July 22, 2015. Customers often generate ideas for outings by perusing such books. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Mike Matson's Take A Hike Salt Lake City included a section on the Lakes Country Trail (which is in some sources labeled Smith Morehouse Trail).

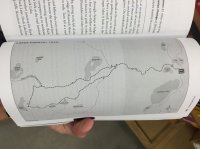

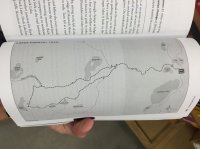

The associated map used a bold dashed line to depict a lollipop loop, with the start and finish at the Crystal Lake Trailhead. The Middle Fork Weber River Trail (not bearing any label) connected to this primary trail. But the map included few named features — just a handful of lakes. It omited any topographical information, not even showing high points, passes or stream drainages.

The section of Mike Matson's Take A Hike Salt Lake City. The map includes no topographic detail. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Matson's book was published in 2013, a full decade after Kim and Carole's disappearance.

A better indicator of what they had available at the time came in the form of Bill Schneider's Hiking Utah. This book was first published in 1991, then revised in 1997 and 2005. It was the 2005 version I found on the shelves at REI, though Kim and Carole would have had the prior edition.

Another title from the shelves at the Salt Lake City REI store on Wednesday, July 22, 2015. Guidebooks are sometimes updated so the quality of information can vary over time. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Hiking Utah had an entry for Three Divide Lakes, describing it as an easy, 6-mile loop. Its map was only marginally better than the one in Take A Hike Salt Lake City.

It showed the Notch Mountain Trail, but as a complete loop beginning at the Crystal Lake Trailhead, topping out at Twin Lakes then returning to the beginning along the west side of Clyde Lake. In reality, the Notch Mountain Trail crosses over The Notch and terminates near Bald Mountain. However, Hiking Utah opts to show that portion of the trail as a small spur, incorrectly applying the Notch Mountain Trail label to what the Forest Service calls the Clyde Lake Trail.

The Lakes Country Trail (which, as described above, provides access to Long Lake and — more importantly — the West Fork Weber River Trail) did not even extend past Crystal Lake. It also misidentified John Lake as Booker Lake.

The Three Divide region as it appears in Hiking Utah. The map does include a few topographical indicators but misidentifies some features. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The trail as shown in Hiking Utah is only somewhat true to the situation on the ground. The link between the Notch Mountain Trail and the Clyde Lake Trail is not considered official by the Forest Service. The split from the Notch Mountain Trail heading to Clyde Lake is not marked with a sign and can be easily missed.

In 2003, the internet was not the font of free hiking information that it has become in 2015. Commercially available resources were Kim and Carole's best options.

It should be obvious that confusion did, and does, exist. It seems entirely possible that Kim and Carole could have known about the existence of the Middle Fork Weber River Trail without understanding the low quality of the trail or the nature of the terrain surrounding it.

Their apparent intent was to complete the loop described in Hiking Utah's Three Divide Lakes section. One of Kim and Carole's photos proves they made it at least as far as the northern end of Clyde Lake.

From there, however, their journey took a severe detour.

The Weather

The Utah State Office of the Medical Examiner ruled Kim and Carole's deaths accidental, with hypothermia the probable cause.

They were not hiking in mid-winter, but instead in early autumn. The U.S. Naval Observatory marked the Autumnal Equinox in 2003 on Sept. 23, two weeks after Kim and Carole arrived in Utah. How then did they fall victim to a cold-weather death?

White-out conditions at Lost Lake along the Mirror Lake Highway on Saturday, May 16, 2015. Media reports about Kim and Carole's ordeal paint a picture of weather like this descending upon them, but that's not supported by the evidence. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

A sheriff's office report described a storm moving through the western Uintas on Sept. 8, the same date as their last known contact. Media reports also said temperatures dropped below freezing that night, with snow blanketing the ground by the night of Sept. 9.

However, there might be some hyperbole in that.

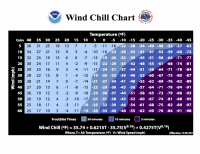

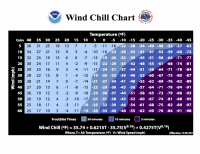

The Trial Lake SNOTEL weather station sits less than a mile away from the Crystal Lake Trailhead. It's been reporting hourly conditions since the late 1970s. It recorded a low temperature of 33 degrees Fahrenheit on Sept. 8. The same is true for the 9th. Those are temperatures near, but not below, the freezing mark. High temperatures both days were in the low 50s.

The area did see rainfall on the 8th, with the SNOTEL station measuring .5 inches of precipitation. Another .2 fell on the 9th.

The Trial Lake snow telemetry station not far from the Crystal Lake Trailhead. Sensors here have long recorded a range of weather indicators, such as temperature and snow depth. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Sept. 10 is when the worst of the storm hit — two days after Kim and Carole had departed for their hike (and presumably, after their deaths). Temperatures plunged. The daytime high reached only 35 degrees Fahrenheit. The low dropped below freezing to 28 degrees. Another half-inch of rain also fell.

Graphical representation of Trial Lake SNOTEL data for the month of September 2003, retrieved and compiled on Wednesday, July 22, 2015. Available as a high-quality PDF here.

The Trial Lake SNOTEL did not measure any snowfall accumulation for the month of September 2003. Neither did the Hayden Fork (9,212 feet ASL), Lakefork Basin (10,966 feet ASL) or Lily Lake (9156 feet ASL) stations.

The Trial Lake SNOTEL station snow pillow, which measures the amount of accumulated snow. This sensor did not record any snowfall for the month of September 2003. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

That's not to say snow didn't come down in the Uintas — multiple media reports describe it happening — so it's quite likely snow dusted the high peaks. The SNOTEL data though shows snow did not stick in a measurable quantity.

More importantly, it did not play a factor in Kim and Carole's deaths.

Dr. Scott McIntosh, M.D., an Associate Professor in the University of Utah's Division of Emergency Medicine, contends cold can kill even when the air doesn't have the bite of winter.

"The human body is not very well equipped to deal with cold temperatures," Scott said. "When you say cold, even temperatures in the 30s, 40s and 50s can still feel cold to a human that doesn't have on a lot of extra clothing."

The body, when exposed to cold, has to work harder in order to maintain its ideal internal temperature. The first line of defense is shivering. Scott believes too many people mistake that involuntary response for hypothermia.

"Shivering is more of a preventative mechanism for the body to prevent the body from going hypothermic, rather than being the first sign of hypothermia."

The SNOTEL data suggests Kim and Carole encountered cool air. That doesn't paint the whole picture, though. The half-inch of rain that fell the day of their hike likely soaked their clothing.

The saying "cotton kills" is a common adage among hikers, referencing the fact cotton loses its insulating capacity when wet. Photos of Carole show she dressed in a T-shirt (likely cotton) and later donned a light, hooded jacket. Kim wore a V-neck sweatshirt.

If their clothing became soaked by rain, perspiration or a mixture of the two, the women would have found themselves in immediate trouble.

"It all depends on the balance of mostly the temperature and the wind," Scott said.

(Image courtesy National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

The Trial Lake SNOTEL site does not include wind speed data from the time of Kim and Carole's hike. Historical wind speed data does exist though for the Heber City Municipal Airport, via MesoWest. The data consists of measurements taken every 15 minutes throughout the day.

The highest wind speed recorded at the airport on Sept. 8, 2003, was seven miles per hour. For most of the day, wind speeds were between two and five miles per hour. That equates to a light breeze on the Beaufort Scale.

The airport is roughly 27 miles away from where Kim's and Carole's remains came to rest. It also sits at an elevation of 5,597 feet above sea level, a full 4,500 feet below the elevation of the final resting place.

Wind gusts can be highly localized, so it is not possible to draw definitive conclusions about wind speeds Kim and Carole encountered. Suffice it to say, the winds that day were not extreme in northern Utah.

A little breeze, some cool air and a relative abundance of rain were all it took.

"The temperature at which the naked human body does not lose nor gain heat is actually 82 degrees," Scott said. "Probably the most common temperatures that people get mildly hypothermic is right around 40 degrees. People don't realize that it's going to be cold because it's probably not snowing out. A sunny fall day that happens to be 40 degrees, you're losing quite a bit of heat, but you might not realize that and therefore wouldn't put on a lot of clothes in response to those temperatures."

The Photos

Film does not feel the effects of hypothermia.

The camera Kim and Carole had carried during their hike survived the long, cold winter months. It ended up in the hands of deputies when they arrived at the shelter to see the scattered contents of Kim and Carole's packs.

KSL obtained permission to publish those online. The Summit County Sheriff's Office also released a single photo for the KSL story. It showed a close-up of Kim and Carole's makeshift rock shelter as it had appeared on the day of its discovery.

Commenters on the KSL story immediately noticed the photos did not show Long Lake, where the sheriff's office continued to claim Kim and Carole had traveled. To prove this point, a local geocaching group started plotting the coordinates where the photos had been taken. Most of the locations were easy to identify, as they had been shot from familiar spots along the Notch Mountain Trail. They showed recognizable features, such as The Notch itself.

The south side of The Notch, as it appears from Wall Lake. Steep, rocky terrain can make cross-country travel in this region difficult. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

A few pictures at the end of the roll proved more difficult to plot, however. They showed a lake in the rain, Carole standing next to a little stream and a small meadow containing a pair of tiny saplings.

In 2007, summitpost.org member Dmitry Pruss and others on his page dedicated to the Beverly/Wetherton case succeeded in proving those photos had been taken from the area immediately surrounding Hidden Lake.

They were unable to locate the rock shelter shown in the sheriff's office picture. Many seemed to presume, based on media reports and rather vague statements from investigators, that it must sit to the west of Hidden Lake in the Middle Fork of the Weber River gorge.

In 2008, summitpost member stripey22 suggested perhaps Kim and Carole had not been lost, but were instead attempting to circle Mount Watson. If that were true, they would have headed south from Hidden Lake, not west.

This idea resonated. In August of 2011, I attempted to test it by hiking along the western foot of Mount Watson in search of the final resting place. While unsuccessful, the outing left me feeling certain Kim and Carole had not just wandered aimlessly.

A public records request to the Summit County Sheriff's Office in December of 2014 provided an even stronger confirmation. Through it, I obtained GPS coordinates for the rock shelter.

Using this information, I succeeded in retracing Kim and Carole's complete path on May 20, 2015.

The Route

The following Google Earth tour gives a basic idea of their journey.

The well-worn trail from the Crystal Lake Trailhead to the Notch is surrounded by lakes and ponds, many of which can at first appear quite similar.

The first three pictures were all taken in close proximity to the trailhead and provide little insight, except in showing what Kim was wearing and the general condition of the weather.

The first picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

The first picture shows Bald Mountain and Reid Mountain, as seen from the Notch Mountain Trail.

Bald and Reid Mountains, as seen from the Notch Mountain Trail on Saturday, June 20, 2015. The location approximates that from Kim and Carole's first photo. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Another view of Bald and Reid Mountains from the Notch Mountain Trail. Features show this image was captured north of where Kim and Carole snapped their picture. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Note that neither of my photos are exact. In their photo, the small cliff band above Star Lake appears to be directly under Reid. In my shots, it's not aligned the same way, proving I was just a bit too far to the north.

Using Google Earth, draw a straight line down from Reid across that cliffy outcrop and intersect it with the Notch Mountain Trail.

That shows the coordinates for this photo were roughly 40.688821, -110.961479.

The second picture. (Photo: Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

The third picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

The second and third pictures are from the shore of a small lake fringed with lily pads and ringed by thick forest. Picture two shows Kim smiling for the camera.

Both of these shots appear to have been taken at Ponds Lake or Lily Lakes, just off of the Crystal Lake Trailhead.

Early morning light over Ponds Lake and Mount Watson on Saturday, Oct. 17, 2015. Water levels and shorelines in these little lakes vary greatly from spring to fall. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

However, they're positioned in the roll after the Bald and Reid Mountains shot, meaning they were either placed out of order by the lab or Kim and Carole backtracked to take the shots.

The latter scenario seems incredibly unlikely, but the former casts doubt about the overall validity of the picture ordering. For the time being, I'm leaving this anomaly unresolved.

Pictures four through six were all taken from the southern edge of Wall Lake (40.69394, -110.96147). They'll look very familiar to anyone who's passed by that area. Four shows the cliffs that give Wall Lake its name, with the summit of Mount Watson peeking up from behind them.

The fourth picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

Mount Watson over the cliffs that give Wall Lake its name. Location approximates that from Kim and Carole's fourth photo. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Picture five shows the view from almost the same spot, but looking north toward the Notch.

The fifth picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

The Wall Lake shoreline, looking north to The Notch. Location approximates that from Kim and Carole's fifth photo. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The Notch and Mount Watson form two unmistakable landmarks in this area of the Uintas and are easy to identify for even novice hikers at Wall Lake.

Picture six shows Carole Wetherton taking a break on the rocky shore.

The sixth picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly, via KSL)

Pictures seven and eight seem impossible to identify at first, as they're just random piles of rock.

The seventh picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

The eighth picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

They actually are part of the earthen dam that helps impound Wall Lake.

Rocks making up the southeastern shore of Wall Lake. The Utah Department of Environmental Quality reports the dam was built in 1914 to enlarge Wall Lake's natural size. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

These two worthless exposures end up seeming more significant later on as Kim and Carole run short of film and take fewer photos. Had they not wasted these two shots, we might have had more evidence of their travels past Hidden Lake.

Pictures nine, 10 and 11 are all from along the Notch Mountain Trail past Wall Lake, looking north toward Notch Mountain. (40.69711, -110.95415)

The ninth picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

A small meadow along the Notch Mountain Trail, below Notch Mountain itself. Location approximates that of Kim and Carole's ninth photo. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The tenth picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

Matching features from Kim and Carole's photos along the Notch Mountain Trial on Saturday, June 20, 2015. Matches are inexact due to minor differences in physical location and lens focal length. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The eleventh picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

Pictures 12 and 13 depict a small pond at the base of a cliff.

The twelfth picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

The thirteenth picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

Cliffs rising behind a small pond north of Wall Lake on the Notch Mountain Trail. Location approximates that of Kim and Carole's thirteenth photo. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

It sits below Hope Lake, before the Notch Mountain Trail starts up a steep set of switchbacks. (40.69906, -110.95359)

Pictures 14 and 15 show that same cliff from the switchbacks, looking southwest toward Haystack Mountain. (40.70042, -110.95313)

The fourteenth picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

The cliffs just below Hope Lake as seen on Saturday, June 20, 2015. Mount Watson sat obscured behind the rocks on the right of the frame. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Note how in picture 15, Carole still wears just a T-shirt. Skies are overcast. The weather had not yet grown sour.

The fifteenth picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

The view south from the cliffs near Hope Lake, showing the Provo River drainage. Location approximates that from Kim and Carole's fifteenth photo. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Lining up the trees from Kim and Carole's fifteenth photo, many of which still stand more than a decade later. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The little pond from pictures 12 and 13 reappears in picture 16, only now it's seen from the top of the cliffs. (40.700232, -110.953804)

The sixteenth picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

The unnamed pond below Hope Lake, with Trial Lake barely visible beyond. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Just a short distance away, Kim and Carole snapped picture 17 looking across Hope Lake to the looming east face of Mount Watson. (40.70111, -110.95318)

The seventeenth picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

Mount Watson's east face looming over Hope Lake. Snow can remain in patches on Uinta peaks until well into the summer. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

After taking a burst of pictures around Wall and Hope Lakes, Kim and Carole seemed to ease off on photography. They skipped any pictures around the Twin Lakes, which they would have passed on their way to Clyde Lake.

That's where picture 18 shows the weather had turned. It reveals the smooth, glacier-carved southeastern shore of Clyde slick with rainwater. (40.70356, -110.96914)

The eighteenth picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

Glacier-smoothed rock on the northeastern shore of Clyde Lake. The lack of shiny reflection in this picture shows just how wet the rock must have been when Kim and Carole shot their picture. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

A wider view of the Clyde Lake shoreline under better weather on Sunday, Oct. 4, 2015. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

A huge gap in photos exists between pictures 18 and 19. From Clyde Lake, Kim and Carole simply needed to follow the single-track trail around the lake's southern tip to start their return trip to the Crystal Lake Trailhead. They didn't.

Pictures 19 and 21 were taken from the outlet of Hidden Lake, which Kim and Carole would have only reached by leaving Clyde Lake headed west. Along the way, they would have passed the Three Divide Lakes, all of which are surrounded by social trails and well-used campsites.

However, once beyond the Three Divide Lakes, Kim and Carole were operating by a different set of rules. The trails faded out and their easy walk would have become more difficult.

If Kim and Carole had become confused here and hoped to regain the trail by following water downhill, doing so on the west side of Three Divide would have carried them farther away from the trailhead instead of closer to it.

On the other hand, Kim and Carole might have made this diversion intentionally. If they had followed the outlet of the westernmost divide lake, it would not have led them to Hidden Lake. That stream does not flow into Hidden, but instead passes by it on the south.

Pictures 19 and 21 prove Kim and Carole made it to Hidden, suggesting they might have gone there on purpose. Both of those pictures were taken within inches of one another, next to a small campsite at Hidden's outlet. (40.70963, -110.98521)

The nineteenth picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

Hidden Lake's outlet. Location approximates that of Kim and Carole's nineteenth photo, though foreground trees have been removed. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The twenty-first picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

A wider view of Hidden Lake's outlet. A small but well-used campfire ring sat just out of frame to the right. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Picture 20 complicates the situation. It shows a small cascade over a rocky ledge surrounded by thick forest. Nothing of that nature exists at the outlet of Hidden Lake. How, then, did this shot end up between two otherwise identical photos?

The twentieth picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

In spite of numerous searches in the area between Three Divide and Hidden Lake, I've been unable to locate picture 20.

I've checked Hidden Lake's primary inlet from Peter Lake.

A small cascade where Peter Lake's outlet tumbles into the eastern shore of Hidden Lake. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

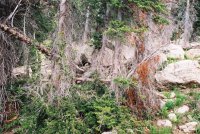

I've followed the streams flowing out of Three Divide Lakes. I've also looked along some of the spring-fed streams issuing forth from the foot of Mount Watson.

A small spring amid heavy timber west of the Three Divide Lakes. Several dry stream channels were present in this vicinity on Saturday, Oct. 17, 2015. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

None have yielded satisfactory results.

This picture might be out of sequence. Again though, assuming so opens up the problematic possibility that any of the other shots may likewise be shuffled.

Pictures 22 and 23 were the last. They were taken at a small campsite along a stream to the south of Hidden Lake. Note that this stream is not Hidden's outlet stream, though it is located very near to the outlet. Kim and Carole did not choose to follow Hidden's outlet down into the Middle Fork of the Weber gorge. They apparently made a conscious decision to leave it and head south. (40.70768, -110.98630)

In picture 22, Carole is now wearing rain gear. She's smiling, showing no expression of fear.

The twenty-second picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly, via KSL)

The author attempting to mimic Carole's pose from Kim and Carole's twenty-second picture. (Photo: Mark Cawley)

Aligning trees from Kim and Carole's photos again, this time at a small meadow south of Hidden Lake. The fire ring has become overgrown in the years since Kim and Carole stopped here. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

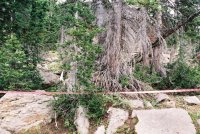

Picture 23 provides the last good clue as to what Kim and Carole were thinking. It looks south toward Long Mountain. In it, the clouds are high and flat. Rain has either stopped or is so light as to not appear evident in the photo. This is a marked improvement from the weather seen in the pictures from Clyde and Hidden Lakes.

The twenty-third and final picture. (Photo: Kim Beverly/Carole Wetherton, via KSL)

The small meadow where Kim and Carole shot their final photo. Two little pine saplings in the center of the meadow have grown since 2003. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Mount Watson sits off frame to the left. Some might note that the distant east Long Mountain appears a bit like Mount Watson. However, it's highly unlikely that Kim and Carole would have mistaken the two landmarks, as Mount Watson had been towering over them for a significant portion of their hike. To have it suddenly appear so distant would not have made any sense.

As mentioned earlier, Kim and Carole's photography was apparently limited by the number of exposures available on the roll of film. Unlike modern digital cameras, where the number of images is constrained only by storage space on internal memory or a removable card, the film camera they carried had very limited and finite number of shots.

The 135 film most often used in disposable or consumer cameras of the era would have likely come with 12, 24 or 36 exposures. From Kim and Carole's camera, we have just 23 images. That suggests a 24-shot roll, with one photo either not taken or not made public by the Wetherton/Beverly family.

The final important shot came not from Kim and Carole, but from the Summit County Sheriff's Office. The sheriff's office provided it to KSL in 2006 for their story about the photos. It showed the rock where Kim and Carole took shelter but its exact location was never made clear.

The rock where searchers found Kim's and Carole's remains, as it appeared on Saturday, June 26, 2004. (Photo: Summit County Sheriff's Office)

Since locating the site and visiting it in person, I have grappled with the ethics of releasing the precise coordinates. The rock sits on public land, open for anyone to visit. However, it likely bears deep emotional significance for Kim and Carole's family, as well as for the searchers who located their remains.

They would probably prefer the location to remain unpublished. On the other hand, it's impossible to tell the story of what actually happened to Kim and Carole without revealing where their journey ended. Just saying it was in the Middle Fork of the Weber River gorge does not provide enough specificity.

Ultimately, the location is a matter of public record. A significant amount of time has also passed since the initial tragedy unfolded. The mystery surrounding the location has in some sense kept the story of Kim and Carole's trip in the public consciousness for more than 10 years. Allowing people to see the location and understand it in context can clarify misunderstandings and help quench the curiosity.

Click here to view on CalTopoThe waypoints above are available as a downloadable KML file here.

The Decisions

Kim and Carole's fate was the result of a series of decisions, each built upon the previous. Some of these choices would have seemed minor in the moment while others bore obvious significance.

In a broad sense, there are four major nodes on their decision tree:

1. Embarking at the Crystal Lake Trailhead

Moments before sunrise at the Crystal Lake Trailhead. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

2. Leaving Clyde Lake

A faint trail leading west beyond the last of the Three Divide Lakes. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

3. Leaving Hidden Lake

Notch Mountain as seen from the southern end of Hidden Lake. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

4. Taking shelter near the Middle Fork of the Weber River

Rocks surrounding Kim and Carole's makeshift shelter site. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

It might seem obvious, but Kim and Carole would not have died (at least not when and where they did) had they never started out on the hike in the first place.

Gray skies over the Crystal Lake Trailhead on Sunday, Oct. 4, 2015. The trailhead is often busy during the summer months to the point of overflowing. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

When they arrived at the Crystal Lake Trailhead, they encountered Brenda Bushell from the U.S. Forest Service.

Did they take the warning seriously enough? They'd come from a part of the country that sees far more annual rainfall than the drought-starved and landlocked West. Their photos suggest weather conditions were not terrible at the outset, perhaps just a bit on the cool side.

The entirety of their experience probably told them Bushell was overstating the situation. They might have reasoned that, in a worst-case scenario, they'd get a bit wet and have to cut the hike short.

A person who is invested, be it in a trip, financial venture or whatever else, may choose to take uncharacteristic risks in order to avoid having that investment fail. In Kim and Carole's case, they had spent a considerable amount of money to fly to Utah and to secure a week of lodging. They'd presumably taken time off work. More than that, they'd poured in time and emotion to plan and to travel.

By the time they reached the trailhead, they had momentum. A simple word of caution was not enough to alter their course.

Once on the trail, pictures suggest they rather enjoyed themselves. Images from early in the roll show Kim and Carole smiling. There are no signs of trouble until Clyde Lake.

An unsigned intersection on the Notch Mountain Trail leading toward Clyde Lake. Rocks lined up were the only indication of where to make the turn. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Here was the second major decision point.

Kim and Carole either chose to leave the trail or lost sight of it. Which was it? No one can say with certainty.

However, the trail around Clyde Lake is not difficult to follow. Navigation is aided by the towering east face of Mount Watson, which is an omnipresent landmark. To the north, The Notch forms another easily recognizable point of reference.

The view north across Clyde Lake to The Notch. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Becoming lost or disoriented at Clyde Lake would have required a complete failure on the part of Kim and Carole to recognize their surroundings.

Their sole photo from Clyde showed rain-slick rock along the eastern shore. The weather, it appears, had turned somewhere between Hope Lake and Clyde Lake. It's pure speculation, but they might have left the trail seeking cover. If so, several obvious campsites in the immediate vicinity of Clyde and the Three Divide could have provided that cover. Why not sit out the storm at one of those then return the way they had come?

Whether they were lost and wandering aimlessly, seeking a place to wait out the weather or intentionally heading for Hidden Lake, Kim and Carole left the trail. By doing so, they turned 180-degrees away from safety.

Going west, they passed by the Three Divide Lakes and crossed from the Provo River drainage into the Weber River drainage.

Threatening skies over Booker Lake and the Three Divide region on Sunday, Oct. 4, 2015. The Provo River originates here. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

An oft-repeated survival strategy instructs lost hikers to follow water downhill to civilization.

When still in the Provo River drainage, they could have done just that. Booker, Clyde and the Twin Lakes all sit at the very headwaters of the Provo. Following any one of their outlet streams would have taken Kim and Carole to Wall and then Trial Lakes — almost directly back to their car.

The area just west of Booker though feeds the Weber. A list of Uinta lakes maintained by the Forest Service shows two of the lakes on the divide empty into the Middle Fork of the Weber River.

A small stream flows downhill from meadows near Three Divide toward the Weber River gorge. Spring snowmelt fed this stream. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

A hiker not understanding this shift and intending to follow water downhill to civilization would face at least 6 miles of rough travel before reaching the summer homes along the Weber Canyon Road. That's a journey of greater distance than the return to the trailhead, through much more difficult terrain.

The third major — and perhaps most critical — decision came when Kim and Carole arrived up at Hidden Lake. Their photos show they stopped next to its outlet. If they'd followed a stream or vague path to that point thinking it was taking them back to the trailhead, the error would have become obvious.

They could have chosen to turn around, heading back uphill for roughly a mile to rejoin the trail at Clyde Lake. Or, they could have headed west, following Hidden Lake's outlet stream downhill into the gorge of the Middle Fork.

The view northwest across the gorge of the Middle Fork of the Weber River from the foot of Mount Watson. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Returning to Clyde would have been the safest option. Had they done so, their odds of surviving would have increased. Proceeding downhill would have been a foolhardy decision. Even if they'd known about cabins in Holiday Park, reaching them would not have been easy.

They did neither. Instead, Kim and Carole chose to do something wholly unexpected.

They abandoned Hidden Lake's outlet stream, walked a short distance to the south and paused for a final couple of photos next to a spring-fed stream.

The campfire ring where Kim and Carole stopped for their final two photos. By Saturday, June 20, 2015 the spot had become overgrown and showed little evidence of human disturbance. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The last shot from the roll looked south across a meadow toward east Long Mountain. It shows the weather had improved. The sky remained overcast, but the cloud deck was well above the more than 11,000-foot peak. Although Carole still wore her jacket's hood in the second-to-last shot, heavy rain did not appear to be an issue in the meadow.

Kim and Carole left an important clue with their photo of this south-facing view toward east Long Mountain. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

So why go south? If they'd been following the water downhill in lieu of a trail, why not continue from Hidden Lake's outlet right into the canyon?

It is possible they were attempting to short-cut their way back to the trailhead. Their decision to head south from Hidden Lake makes little sense, unless one believes they decided to attempt a large loop around Mount Watson.

The only rational objective for them to the south would have been the Middle Fork Weber River Trail. Following that over the saddle between Long Mountain and Mount Watson would have brought them to the intersection with the Lakes Country Trail, just east of Long Lake.

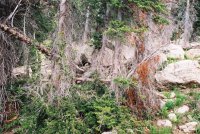

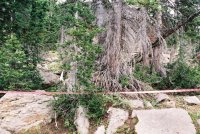

The trouble is, the terrain grows difficult beyond the location of those final two photos. It's relatively simple to navigate along the 10,200-foot contour line south from that place, but one must hurdle downed trees, dodge cliff bands and avoid frequent rockfall.

The view south toward east Long Mountain from near the 10,200-foot contour line at the western foot of Mount Watson. The tree-covered ridge on the left of frame would have been Kim and Carole's goal. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Their shelter sits a mere .08 of a mile from the Middle Fork Weber River Trail. That's only about 420 feet.

From there a short, steep hike followed by three easy miles on a well-trodden trail would have brought them home.

The Cenotaph

The fourth and final decision was the one to halt their hike.

I preface any discussion of Kim and Carole's shelter with a personal plea. That rock could be seen in the same light as a headstone. As such, I've taken to calling it the Cenotaph, as a reminder of what was suffered and lost there. The sheriff's office records suggest Kim and Carole's remains were scattered. That might explain why investigators were hesitant to share the exact location.

In other words, Kim and Carole left part of themselves on the mountain. They deserve to rest in peace. If you choose to visit, please show their family respect by stepping lightly and leaving no trace.

The rock shelter did not scream out for attention as I approached it from the north.

The author's first view of the shelter rock on Saturday, June 20, 2015. The location was not obvious until almost on top of it. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Its front, the face with the cleft in which Kim and Carole sought cover, is surrounded by pine trees and underbrush. The ground falls before it and the trees obscure the view of the Middle Fork of the Weber drainage. Stepping out of the glade to either side provides expansive views of Long Mountain and the Weber River gorge itself.

West-facing view from near the Cenotaph with Long Mountain partially obscured by trees. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The back, by contrast is open. The steep hillside rises behind it, climbing up toward Mount Watson. The mountain itself is blocked from view.

East-facing view from behind the Cenotaph. The steep grade eclipsed any sight of Mount Watson. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Soil around the shelter is rocky, filled with cobbles ranging from small pebbles to larger, half-buried slabs. Meadow grasses and wildflowers are abundant. A small stream tumbles down the hillside a short distance to the north and is audible from the spot.

The cleft is formed by two pieces of the same rock which were at some point in time split. The primary chunk is partially buried. It rises about 5 feet out of the ground. The second piece is a slab which is tilted against the first. The slab is cracked in half, with the front half rotated forward.

The front cleft of the Cenotaph. Before being split, the boulder was perhaps the size of a small car. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

A hollow space opens between the two pieces of rock at the level of the ground. This is the cleft. It's small, too small to hold a single adult, let alone two. A child could squeeze in, but would have to contort his or her body in order to do so.

So how did Kim and Carole manage to find shelter in that cleft? Investigators described finding pieces of a mylar emergency blanket jammed into the narrow gap above the cleft, in an apparent effort to block out the rain. Images gathered by the Summit County Sheriff's Office (available in Addendum B below) also show a long, straight piece of pine resting in the joint formed where the two pieces of rock rest against one another.

While soaked and hypothermic, Kim and Carole apparently removed their soggy layers. The photos taken by investigators at the site showed just this — Kim's sweatshirt hanging from the pole. Deputies supposed the clothing had been hung to dry. Kim might have instead though used her wet clothing as a sort of curtain, blocking rain from entering the mouth of the cleft.

A close-up look at the Cenotaph cleft. The hollow was more shallow than shadows seemed to suggest. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

But why choose that space?

As Kim and Carole headed south from Hidden Lake, they were traversing the western foot of Mount Watson. Hiking uphill to the 10,400 contour line as it appears on the Mirror Lake quad would have brought them above tree line. Here, they would have found more manageable terrain for cross-country travel, not unlike what they encountered between the Three Divide and Hidden Lakes.

However, had they done this, they would have crossed well above the location of the Cenotaph and arrived at the saddle above Long Lake.

A pond at the headwaters of the Weber River on the saddle between Long Mountain and Mount Watson. It took less than 30 minutes to walk from this spot to the Cenotaph. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

It's likely they attempted to stay at about the same elevation as that of their final picture, along the 10,200 contour line. As they proceeded south, the slope they were traversing increased in grade. The meadows gave away to hillsides tangled with timber, both standing and down.

A small cascading stream immediately to the north of the Cenotaph. Descending this uneven slope required special caution. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

This is the path I took on my first visit to the Cenotaph. About .1 mile from the shelter, I reached a small stream. Not seeing an easy place to cross, I descended the hill on the stream's north bank. My dry soles slid on the loose ground. This necessitated using my hands to arrest a slide. Had the ground been wet from rain, I'd have lost balance and tumbled down the steep slope.

An example of the rugged landscape found on the slopes above the Middle Fork of the Weber River. Kim and Carole would have crossed this type of ground while it was slick with rain. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Could either Kim or Carole have fallen in such a manner while making their way down a rain-soaked hill? In such a circumstance, the Cenotaph would have been the best of the bad options for shelter close at hand.

Another plausible explanation exists in the descending darkness. In early September, nightfall comes to the Uintas just before 8 p.m. Overcast skies would have muted the twilight. Stumbling through the dim, Kim and Carole might have decided moving forward in the dark presented too much difficulty or danger.

Or perhaps it was a combination of these factors. Injury, darkness and fatigue from a long day of hiking at elevations exceeding 10,000 feet may have worked together to slow and ultimately stop them.

Though faint, small paths used by wild animals and the occasional horse packer cross the slope just north of the Cenotaph rock.

Perhaps Kim and Carole found one of these paths and followed it down to the Cenotaph in the fading light, breathing hard or limping on a turned ankle.

A faint path descending a steep hill toward the Cenotaph. This path showed obvious signs of use by wildlife and horses. (Photos: Dave Cawley)

It is my belief that either Kim, Carole or both became injured not far from their shelter location. Unable to continue, they found the nearest safe place to stop and wait out the night.

If they had indeed been attempting to circle Mount Watson, they came very close. They probably didn't realize just how close.

But, as mentioned above, the Middle Fork Weber River Trail would not have been easy to spot. Kim and Carole had no GPS receiver and, as far as is known, only basic maps. The fine detail provided by modern navigational aids was not available to them.

Even if uninjured, Kim and Carole might have wondered why they had not yet reached the trail and stopped out of sheer fear or frustration.

A hiker stopping in cold weather and gathering darkness can feel the inherent risk of that situation. Kim and Carole would have been soaked by rain and sweat, exhausted and probably quite scared. Coming to a halt would have meant growing even colder.

"If you're in that pre-hypothermic stage or even that mild hypothermic stage… even just the simple act of walking on level ground can raise your core temperature up just slightly to prevent that temperature from going lower," Dr. McIntosh said. "If you have enough calories on board and have a set destination, for example if you know that there's a hut two miles away and you can walk slowly to that hut without depleting your calorie stores and just becoming completely exhausted, then absolutely that would be the best way to go."

That's even more true in Kim and Carole's case, since no one was coming to their aid. Unfortunately, rescue professionals often advise people to stop and stay put if they ever get lost. In reality, the wisdom of that advice is highly situational.

"It's always a challenging decision because it's usually best to wait for rescue. However, if there's no rescue coming then you are your own rescue," Dr. McIntosh said.

Continuing to walk could have helped stave off hypothermia, at least for a time. Instead, the women appear to have given up on hiking, choosing to seek shelter.

The investigators found an open first-aid kit at the site. They mentioned medical tape "lying out." It could have been scattered by animals or it could be evidence of an injury — a rolled ankle or laceration, perhaps. Kim and Carole's remains had been preyed upon by animals, likely coyotes, destroying any evidence that could have supported this theory.

At the Cenotaph, the mother and daughter apparently huddled together, trying to conserve what body heat they could. The search and rescuers presumed they died on the first night.

A view of the south side of the shelter rock, looking north. The timber surrounding the site kept it out of view from searchers who scanned the Middle Fork Weber River Trail. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Dr. McIntosh said the body goes through three general stages as the symptoms of hypothermia take hold.

"The early stages of hypothermia, people are still shivering and sometimes they can be a little bit confused and maybe stumbling around a little bit, but they're still awake and alert and making sense. Then when you get to the moderate stage, shivering stops. Basically, your body has determined that whatever it has been doing is not working and therefore it tries to conserve its energy rather than expend it by shivering to increase its heat production. As the body goes through the cooling process even further, then you can go into a coma. Your heart can start to have spontaneous bad rhythms. When you're in the severe hypothermia stages, you can have spontaneous bad rhythms that are fatal."

The Long Lake Theory

Some might still refuse the theory that Kim and Carole made an effort to circle Mount Watson, intentional or otherwise.

The photos prove Kim and Carole hiked to Hidden Lake. This is irrefutable. So the primary alternative theory, the one promoted by the Summit County Sheriff's Office, requires accepting the idea Kim and Carole returned safely from Hidden Lake on Sept. 8.

If this was the case, consider the sequence of events required.

First, Kim and Carole would have had to venture out for a second day under similar or even worse weather conditions (assuming they hiked again on Tuesday or Wednesday), without making any significant changes to their planning or equipment after their experiences in the rain on Monday.

Second, they would have left a well-defined trail for no obvious purpose. Remember, when Kim and Carole diverted off the Notch Mountain Trail onto the loop route passing by Clyde Lake, they were doing so with an objective. They'd researched the route in guidebooks.

The same cannot be said for the Middle Fork Weber River Trail. It is so slightly used, in part, because it doesn't lead to any high-interest destinations. Trail guides do not highlight it. The trail is primarily used by people on horseback.

So perhaps, the theory goes, they didn't mean to leave the Lakes Country Trail and were just confused. Maybe hypothermia impaired their judgement on the return hike from Long Lake.

Morning sun on east Long Mountain and Long Lake, with the saddle between Long Mountain and Mount Watson on the right of the frame. Kim and Carole's shelter was on the far side of that ridge. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Maybe they mistook Long Mountain for Mount Watson and lost their bearings.

Morning sun on Mount Watson, reflected in Watson Lake. From some angles, Mount Watson can appear similar to nearby east Long Mountain. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The turn-off for the Middle Fork Weber River Trail from the broad and beaten Lakes Country Trail is marked by a large cairn, but no sign. The Lakes Country Trail here is straight. It is not easy to confuse the two. In fact, many hikers pass right by the intersection with the Middle Fork Weber River Trail without even realizing it exists.

A rock pile marks where the faint Middle Fork Weber River Trail leaves the well-traveled Lakes Country Trail in a T-shaped intersection. Summit County deputies suggested this is where Kim and Carole became lost. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

The Middle Fork Weber River Trail branches off heading north and going uphill. It is an at times invisible single-track path as it climbs toward the saddle above Long Lake.

An indistinct portion of the Middle Fork Weber River Trail where it crosses the saddle east of Long Mountain. Vegetation has completely obscured the trail in many places. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

Under this theory, Kim and Carole somehow managed to mistake the Middle Fork Weber River Trail for the Lakes Country Trail, the latter of which they should have recognized after hiking in on it from the Crystal Lake Trailhead.

This video shows the approximate path the Summit County Sheriff's Office suggested Kim and Carole traveled. Map image courtesy U.S. Geological Survey.

Upon crossing the divide above Long Lake, they would have then failed to recognize just how different the terrain appeared compared to what they'd already seen.

A cairn marks the route of the Middle Fork Weber River Trail at the top of the saddle east of Long Mountain. Following the trail required crossing meadows guided only by cairns. (Photo: Dave Cawley)

From my personal experience, this idea does not hold up to scrutiny.

If anything, hiking the path search and rescuers proposed in 2004 will only serve to reinforce the concept Kim and Carole actually came around Mount Watson from the north.

They may have become lost. If so, that happened near Clyde Lake, not Long Lake. They crossed a saddle, but it was at Three Divide, not above Long Lake.

They deserve credit for enduring a slog through poor weather, stopping only after covering miles of rough — and at times confusing — high-elevation terrain.

The Summit County Sheriff's Office also deserves credit for staging a thorough and robust effort to find them. The rescuers had limited information to go on and covered a large amount of ground in a short amount of time. They had no reason to suspect at the time Kim and Carole would have taken the route that they did, yet came very close to finding their shelter in the first few days of the mission.

Reality TV has attempted to turn "survival" into a form of entertainment. That's just theater. True survival is having to make snap decisions in an unfamiliar environment, all while facing stiff consequences. Kim and Carole did that. Though they lost their lives, they at the end knew more about survival than anyone who eats bugs on television. Someone filming a TV show off the side of a state highway does not face the same stakes.

Kim and Carole did make mistakes. They did not sign in at the trailhead register. They did not detail their itinerary or plan to check in at the conclusion of their hike. They did not press on when rescue was potentially as close as a 30-minute walk from where they had stopped. They remained together when perhaps, if one of them had become injured, separating could have increased their likelihood of finding help.

Anyone who spends time in the backcountry can learn lessons from these errors. By understanding and internalizing what happened to Kim and Carole, one can let their experience inform future decisions and, with luck, avoid a similar fate.

Acknowledgments

This report stands on the shoulders of good work by many journalists, chief among them KSL's Marc Giauque. His 2006 story, which made Kim and Carole's photos public, proved key in illuminating their experience. Likewise, the efforts of the Utah geocachers group and Dmitry Pruss on summitpost.org were an invaluable resource.

I owe @Nick from Backcountrypost a special thanks for enduring my badgering to get this report online. Thank you as well to my brother, Mark, for his assistance in gathering aerial imagery of the search area.

The Summit County Sheriff's Office deserves credit as well for their transparency in retrieving and providing records from the search and recovery.

Finally, thank you to the proofreaders who took time to smooth over the rough edges.

Addendum A - Timeline

9/8/2003 — Kim and Carole arrive at the Crystal Lake TH off Highway 150. FS ranger contacts them, advises they need better clothing for the weather. Kim and Carole possibly depart, then return.

9/13/2003 — Kim and Carole are reported missing after missing their flight to Georgia. Summit County deputy hears ATL for missing hikers broadcast on behalf on Park City Police.

9/14/2003 — Deputy locates Kim and Carole's rental vehicle at the Crystal Lake TH, launches search and rescue effort. Bloodhounds catch scent and head down the trail to Wall Lake. Items in the Jeep and Park City condo indicate interest in Wall and Clyde Lakes. "Hasty teams" run the area trails.

9/24/2003 — Search scaled back to weekends only after 10 straight days of active operations.

6/5/2004 — Reconnaissance team comes within 100 yards of shelter.

6/26/2004 — Rocky Mountain Search Dog team training in the Middle Fork of the Weber River drainage discover human remains in makeshift shelter. Deputies secure the location and spend the night.

6/27/2004 — Summit County Sheriff's Office transports the remains to the Office of the Utah State Medical Examiner in Salt Lake City for forensic analysis. Deputies continue gathering remains and evidence from the site.

6/28/2004 — Forensic anthropologist inspects bones, determines they represent two individuals. Criminalist recovers DNA from tissue on the bones.

6/30/2004 — DNA results indicate some of the bones belong to Kim Beverly. Deputies notify Wetherton/Beverly family.

7/6/2004 — Summit County takes remaining bone to Myriad Genetics.

7/9/2004 — Myriad reports DNA results from the bone. Summit County confirms identity of Carole Wetherton. State Medical Examiner determines likely cause of death was hypothermia, accidental. Deputies notify Wetherton/Beverly family.

9/28/2006 — KSL publishes photos recovered from Kim and Carole's camera. Commenters immediately note a disparity between the account offered by Summit County S.O. and what the photos show. Utah geocacher groups begin to plot course revealed by photographs.

10/22/2006 — Summitpost user Dmitry Pruss publishes a page detailing efforts to locate Kim and Carole's final resting place. The page is updated in July of 2007 with the locations of the final two shots on the roll. Photos prove Kim and Carole started on the Notch Mountain Trail, likely with the intent of completing the connection to Clyde Lake. Instead of returning to the Crystal Lake TH, they ended up south of Hidden Lake.

11/16/2010 — Summitpost user stripey22 suggests in comments the theory that Kim and Carole were not lost but instead intended to circle Mount Watson.

8/27/2011 — During a visit to the Middle Fork of the Weber area in an attempt to locate the final resting place, I come within .4 miles of its location. The visit reinforces in my mind the concept that Kim and Carole intended to circle Mount Watson.

6/20/2015 — I make my first visit to the final resting place while completing a circumnavigation of Mount Watson, following Kim and Carole's path.

7/18/2015 — I make a second visit to the site, this time approaching from Long Lake on the path suggested by Summit County SAR.

10/10/2015 — I make a third and final visit to the site, completing a reverse of Kim and Carole's path.

Addendum B - Summit County photos

The public records request that resulted in my obtaining the GPS coordinates for the shelter rock also included photos of the site as it appeared when discovered in 2004.

The request I made asked for any photos that would help in locating or identifying the location. However, in discussion with the Summit County Sheriff's Office, I agreed to let them withhold photos that depicted human remains. This was in deference to the Beverly/Wetherton families.